Finding the place for faces

She raised cormorants in her back yard in a kid’s swimming pool and studied the psychology of nuclear war on a MacArthur grant. But Kavli Award winner and cognitive neuroscientist Nancy Kanwisher always found herself coming back to studying the workings of the human mind.

When Nancy Kanwisher began studying the brain as a young researcher using functional MRI in the spring of 1995, she had to scramble for valuable machine time and work early hours on the weekends to do her work.

The field was so new and the competition for machine time was so great that Kanwisher, then a junior faculty member at Harvard, felt under pressure to come up with a discovery, fast, with the three hours a week she had on the machine.

“After a few months without much success, I became worried,” Kanwisher wrote in a 2017 paper in The Journal of Neuroscience describing her quest. “Scan time was expensive, I did not have a grant, and I was at risk of losing my scanner access if my team did not score a big result fast.”

I thought, oh my God, all of these basic questions that we’re grappling with in cognitive science. You could just look inside the brain.

So, what was the easiest road to a big win?

Kanwisher knew, from previous research and clinical evidence, that if there were to be any part of the brain where neurons could be identified as focused on a specific task, it would likely involve facial recognition.

“I had never worked on face perception because I considered it to be a special case… But I needed to stop messing around and discover something, so I cultivated an interest in faces,” she wrote in the 2017 paper.

Her persistence led her to discover a specific area of the brain that responds preferentially to faces – and helped pioneer the study of functionally distinctive areas of the brain.

For this work, the Kavli Prize in Neuroscience for 2024 was awarded to Kanwisher, along with Winrich Freiwald and Doris Tsao, who subsequently built on her work to study similar facial recognition patches in macaque monkeys. Kanwisher is currently the Walter A. Rosenblith professor of cognitive neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Nobel laureate and neuroscientist John O’Keefe, a member of the Kavli Awards committee, described their combined efforts as “a beautiful model of how you go about analyzing the way in which the brain represents a particular feature of the world.”

Looking inside the brain

Kanwisher’s previous work had been in cognitive psychology, with her PhD on a phenomenon called repetition blindness.

‘Just by measuring reaction times, you can infer all this stuff?’ And it hadn’t really dawned on me how magnificent the enterprise was from such humble data.

But ever since the first pictures of the brain from PET scans were published in the early 1980s, she had been fascinated by the possibility of being able to watch the brain at work, rather than to infer what was happening from carefully crafted experiments. A decade later, when fMRI proved to be even more suited than PET scans to visualizing what was happening in the brain, she felt compelled to try to get in on the action.

“I thought, oh my God, all of these basic questions that we’re grappling with in cognitive science. You could just look inside,” the brain, she told podcast host Cody Kommers on the Cognitive Revolution podcast.

She was so excited about the technology that she had turned town a near-certain tenure job at UCLA for a not-so-secure position at Harvard, just so she could be closer to the action at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, then a hotbed of fMRI research.

Raising cormorants

What actually goes into making a successful neuroscientist? In her autobiography written for the Kavli Prize, Kanwisher attributes her career in part to luck. She was also steeped in science from her childhood, thanks to her upbringing in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, a community full of researchers working for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI).

“Mine is not one of those inspiring stories of people who found their way to science against all odds,” she wrote in her Kavli Prize autobiography. “I grew up in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where science was handed to me on a platter.”

One of the most striking examples of this involved her father, John Kanwisher, who was a field biologist at WHOI. In 1979, John Kanwisher welcomed a young Norwegian summer student, Geir Wing Gabrielsen, to Woods Hole to do research on white sharks and diving responses in birds. Gabrielsen went on to become a widely recognized seabird researcher who now specializes on environmental pollutants at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Geir Wing Gabrielsen, now a biologist at the Norwegian Polar Institute, and Kavli Prize winner Nancy Kanwisher back in 1979, when Gabrielsen came to study with Kanwisher’s father, John. As part of their research, Gabrielsen and Kanwisher raised cormorants and Canada geese to study their physiological response to diving. The research resulted in an article in Science magazine – a first, but not the last, for Nancy Kanwisher. Photo: Private

Nancy, at that time an undergraduate at MIT, participated in a project with Gabrielsen and her father on diving responses in free-living cormorants and Canada geese that was published in Science magazine. The trio raised two cormorants (Phalacrocorax auratus) from when they were two weeks old and two Canada geese (Branta canadensis) from hatchlings.

They were able to show that free-living diving birds “do not exhibit the ‘classic’ diving response that was described in the literature at the time (where birds have a dramatic reduction in heart rate),” Gabrielsen wrote in an email about their work together. “When we held the cormorant and forced it to dive, we recorded a dramatic reduction in heart rate. That response, which was described in the literature at the time, was (actually) a fear response.”

The birds imprinted on Gabrielsen and Nancy Kanwisher, so that even after they were released to the wild, they recognized their “parents,” Gabrielsen said.

One time, during a garden party at the Kanwisher’s boathouse in Woods Hole, “Willy” the cormorant came flying along with three other wild cormorants.

“I called out to ‘Willy’ who came flying down from the sky, landed on the dock, where he caught a fish before taking off from the dock again. This was a magical moment for both us and the guests,” he wrote.

Even then, Gabrielsen wrote, he could see Nancy Kanwisher’s interest in neuroscience blossoming, especially after they took a course together on the subject that same summer at the Marine Biological Laboratory, also in Woods Hole.

“I’m not surprised that neuroscience became her field of research,” he wrote.

Discovering the beauty of “humble data”

Kanwisher’s brief foray into animal physiology was the first, but not the last time the Kavli laureate explored alternative career options.

Although she started as an undergraduate biology major at MIT, she discovered she wasn’t altogether happy with some aspects of lab work.

“Every time I had to do an experiment, you know, I was working in a blood cell different differentiation lab, and the first thing I had to is grab a mouse and put a pencil behind its neck and pull up its tail and break its neck,” she said on the Cognitive Revolution podcast. “And so, I just thought I need to work in a department where they don’t kill their subjects first…and that might be the psychology department.”

An undergraduate course taught by Molly Potter led Kanwisher to discover the power of behavioral data in helping researchers understand the workings of the mind.

Reading the course textbook, “I just remember thinking, ‘What? Just by measuring reaction times, you can infer all this stuff?’ And it hadn’t really dawned on me how magnificent the enterprise was from such humble data. And that was just totally thrilling,” she said on the Cognitive Revolution podcast.

But as a grad student in Potter’s lab, her behavioral experiments on sentence understanding and visual perception failed to yield useful data. “The questions were exciting and the experimental logic appealing, but most of my experiments bombed,” Kanwisher wrote in her Kavli autobiography.

Science journalism, nuclear war and an unfailing mentor

Frustrated, she dropped out of graduate school several times to try her hand as a journalist. She interned for a summer at the Center for Investigative Journalism in San Francisco. She went to Nicaragua for a month during the height of the Contra war in the 1980s, “faked myself a press pass, hitchhikked all over the country in Army Jeeps, and hung out at the Hotel Intercontinental pool where the US spooks running the war out of Honduras hung out,” she said in an “unofficial story” written for a Growing Up in Science online event in 2021.

But each time Kanwisher would drop out, Potter would welcome her back to the lab with open arms. “Molly was ever patient, insisting that my experimental ideas were good and I was just unlucky with the data,” Kanwisher wrote in her Kavli autobiography.

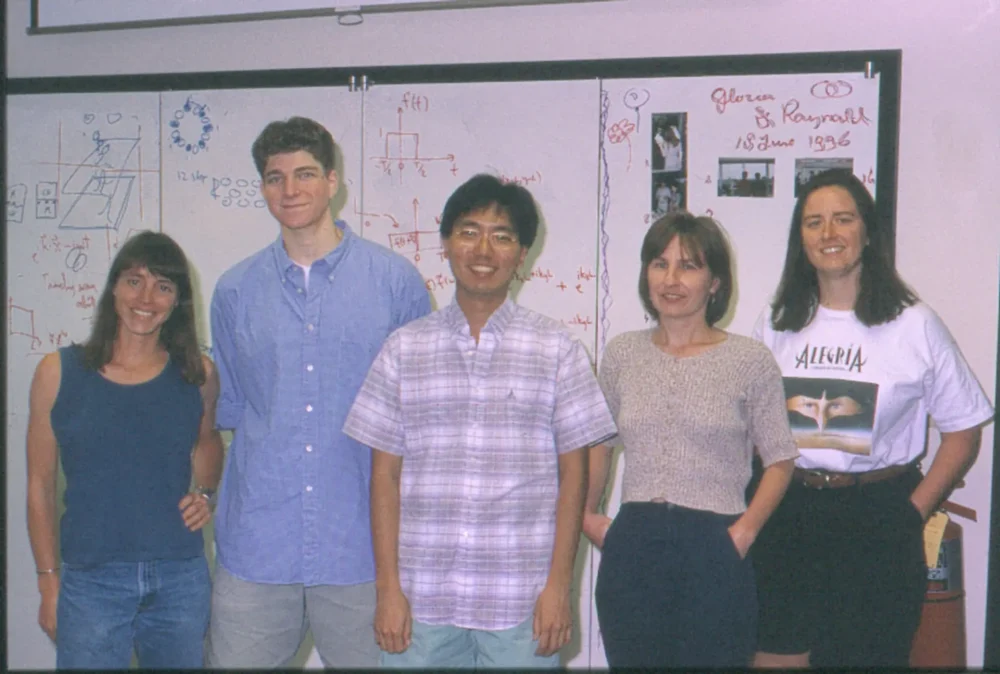

The Kanwisher lab circa 1996. From left to right: Nancy, Josh McDermott (then an undergrad, now head of his own lab at MIT), Marvin Chun (postdoc), Ewa Wojciulik (postdoc), and Jody Culham (grad student).This is the crew that helped Kanwisher do her first fMRI studies, which led to the discovery of the fusiform face area in the brain. Photo: Courtesy Kavli Prize

Eventually, with Potter’s encouragement, Kanwisher explored an idea that Potter and colleague Helene Intraub had first discovered on “repetition blindness,” and completed her PhD in 1986.

But by then, Kanwisher decided that perhaps she wasn’t actually cut out for a career as a research scientist, and instead became a MacArthur Fellow in Peace and International Security.

Here she thought she might be able to bring her background in psychology to bear on better understanding nuclear strategy, “trying to diagnose the cognitive biases that perpetuated misconceptions about US foreign and military policy,” she wrote in her Kavli autobiography.

“It was fascinating and entertaining but I ultimately decided that the real causes, the kind of root causes of bad foreign and military policy have more to do with economic forces that were driving arms production than psychological biases. Of course it’s both, but …I didn’t feel like my efforts to do psychology experiments to illuminate it were being all that helpful,” she said on the Cognitive Revolution podcast.

Kanwisher has continued her engagement in the broader world, by co-launching HarvardMIT Divest from Israel in the early 2000s, by publishing an ad in the NYT warning against an attack on Iraq signed by tens of thousands of American academics, and most recently by supporting the MIT students protesting the bombing of Gaza.

A grant and a gamble

A US National Institutes of Health grant brought Kanwisher back to academia, this time as a postdoc at UC Berkeley working with psychologist Anne Treisman, pursuing her work on repetition blindness. But even as this work led to the offer of a faculty position at UCLA, Kanwisher was still trying to figure out how she could move into using new and developing imaging technologies to further her research.

The questions were exciting and the experimental logic appealing, but most of my experiments bombed.

She eventually got time in a PET imaging lab, run by UCLA’s John Mazziotta, ran some experiments and published her results, but by then fMRI was becoming increasingly important as a brain imaging tool.

Only a handful of labs had the expensive equipment, most notably the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital. So, when a Harvard position opened in the early 1990s, she jumped on it. The rest, as they say, is history.

Finding other ways to understand human cognition

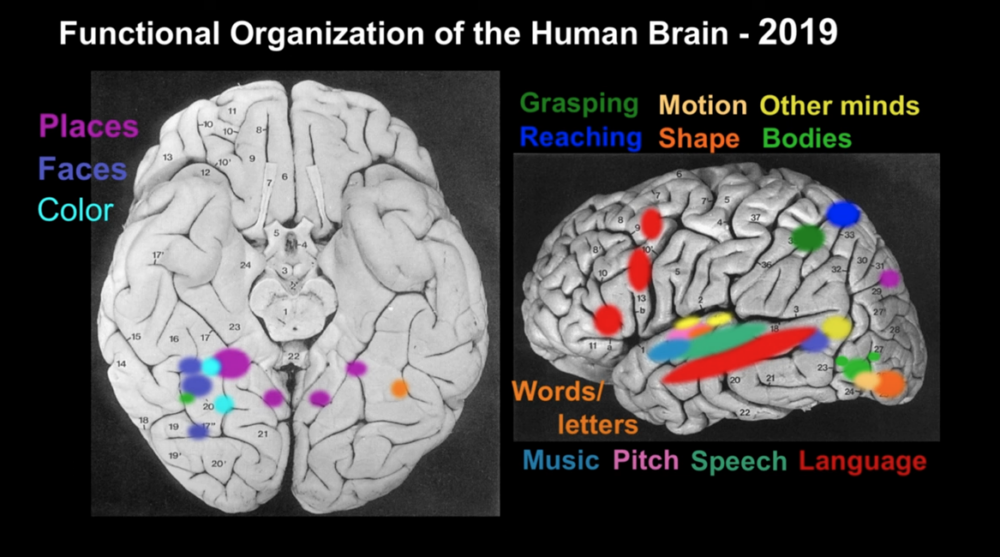

Finding the fusiform face area – and developing a method that would allow researchers to study functional regions of interest – opened the door to Kanwisher and others to discover many other specialized areas in the brain, including those that respond to bodies (the extrastriate body area), scenes (the parahippocampal place area), and even singing.

Some of the different areas of the brain that have been identified by Kanwisher and others, with the help of fMRI and other research tools. Photo: Screenshot

One of Kanwisher’s former PhD students, Rebecca Saxe, now the John W. Jarve (1978) Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience and Associate Dean of Science at MIT, used fMRI to identify an area of the brain that is activated when people think about other people’s thoughts.

“Nancy’s work over the past two decades has argued that many aspects of human cognition are supported by specialized neural circuitry, a conclusion that stands in contrast to our subjective sense of a singular mental experience. She has made profound contributions to the psychological and cognitive sciences,” said Robert Desimone, director of MIT’s McGovern Institute, when Kanwisher received the 2022 National Academy of Sciences Award in the Neurosciences.

More recently, Kanwisher has been using other tools to understand human cognition. Artificial intelligence and artificial neural networks seemed like a natural sandbox: could brain researchers learn from the ways that artificial neural networks solved tasks such as, say, identifying faces?

One of Kanwisher’s postdocs, Katharina Dobs, who is now a research group leader at Justus Liebig University Giessen in Germany, asked that exact question. She trained an artificial neural network to recognize faces – and found that the ANN and the brain used a similar solution, which is to devote a separate part of the network – or brain – to the task.

“That’s what we’ve been looking at in the brain for 20-some years,” Kanwisher said in an 2022 MIT press release about the find. “Why do we have a separate system for face recognition in the brain? This tells me it is because that is what an optimized solution looks like.”

Giving her all in teaching and outreach

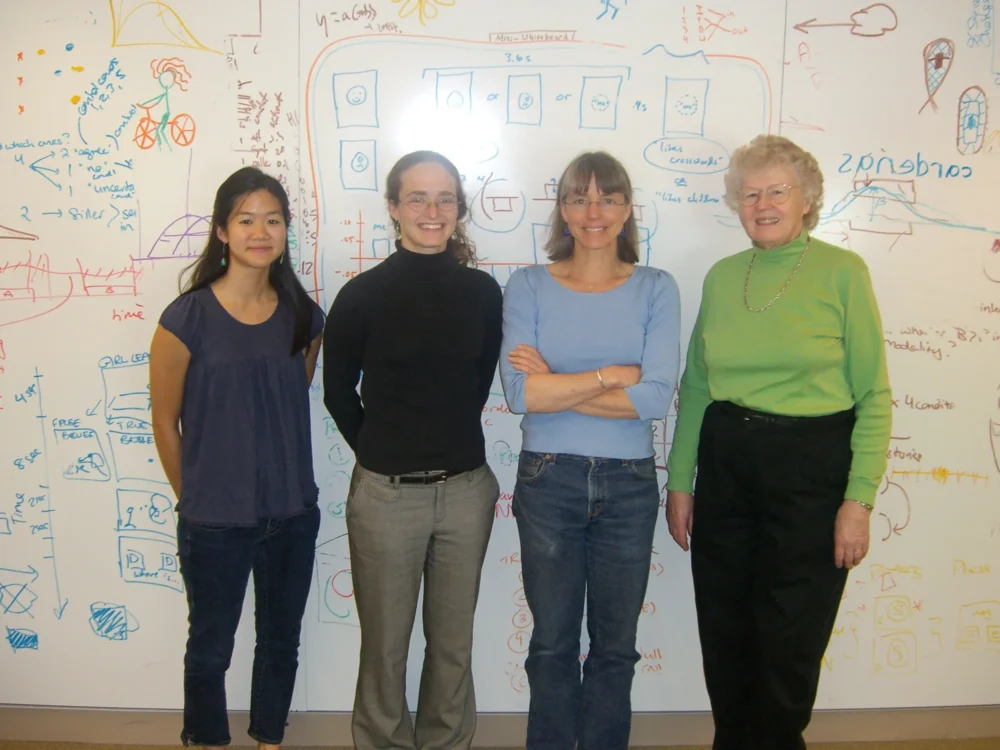

A picture of Kanwisher’s extensive academic footprint wouldn’t be complete without recognizing her commitment to teaching and public outreach. Mentored by the groundbreaking psychologist, Molly Potter, Kanwisher is part of a four-generation female lineage that underscores the importance of mentoring female researchers.

A four-generation scientific matriarchy at MIT. From right to left: Kanwisher’s mentor and PhD.advisor Molly Potter, Kanwisher, her former PhD student (and now colleague) Rebecca Saxe, on the day of the PhD thesis defense of her own student Liane Young (now a professor at Boston College). Photo: Courtesy Kavli Prize

Her MIT website, Nancy’s Brain Talks, which includes lectures from her undergraduate course, has attracted thousands of views. Her TED Talk video, “A neural portrait of the human mind,” has racked up nearly 1.5 million views since it was published in 2014.

She is also unafraid of sharing, whether it is through personal stories or surprising stunts.

“People like stories and people resonate to stories,” she said on Chalk Talk, a podcast published by MIT OpenCourseWare. Her first lecture in her introductory undergraduate course starts with a personal story about a friend who collapsed on the floor of her house – and subsequently proved to have a benign brain tumor in an area that Kanwisher’s lab had been studying.

Viewer numbers confirm Kanwisher’s sense of storytelling: that first lecture video broke MIT Open Courseware’s 20-year record for the most views, with more than 10 million views.

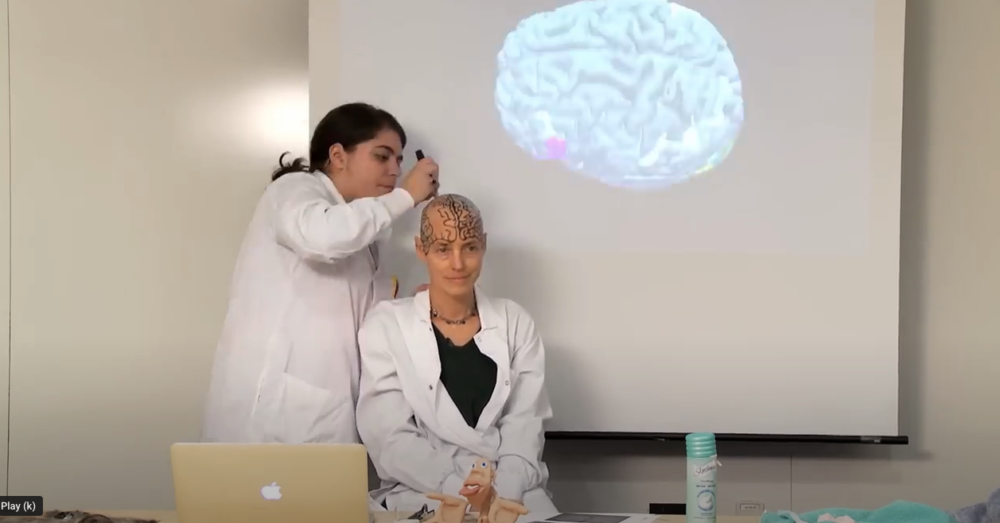

Anything for science education: Kavli prize winner Nancy Kanwisher shaved her head so that students in her undergraduate class could better see different areas in the brain, aided by neuro artist and grad student Rosa Lafer-Sousa. Photo: Screenshot

Another lecture on neuroanatomy begins with Kanwisher telling her students how hard it is to see where different areas of the brain are, because hair gets in the way. So she had her graduate student shave her head and draw a map of the brain on her bald scalp.

“It was fun. It grows back. Who cares?” Kanwisher said in an article about the lecture on BuzzFeed. “Science is an adventure. Shaving your head is kind of an adventure. To be an effective science teacher, you need to have a theatrical bent.”

It’s possible to hear echoes of the scientist who considered becoming a journalist in her reasons for sharing science.

“The public pays for the science we do in the lab, so I think it’s a moral obligation of scientists to give back,” she said on the Chalk Talk podcast.

Nevertheless, Kanwisher is clear when it comes to explaining her enthusiasm for her field. It’s the pure joy of exploring fundamental questions, she says, not necessarily finding a cure for Alzheimer’s or other brain disorders.

“That’s a hugely important goal, and I’d be thrilled if any of my work contributed to it, but fixing things that are broken in the world is not the only thing that’s worth doing,” she says on her TED Talk video. “The effort to understand the human mind and brain is worthwhile even if it never led to the treatment of a single disease. What could be more thrilling than to understand the fundamental mechanisms that underlie human experience, to understand, in essence, who we are? This is, I think, the greatest scientific quest of all time.”