Let there be light!

Do you hunger for daylight indoors? A glass plate or some prisms can give you more of it.

Our biological clock depends on exposure to daylight to function properly. But the modern worker spends more and more time indoors, and our buildings are built ever taller and closer together. Often it’s impossible to see the sky outside our office windows. Sometimes the only way to get a glimpse of the sun is to be one of the lucky few who gets a desk by the window.

There’s more to a window desk than just a good view: in fact, nearly all daylight concentrates in the small area next to the window. So what about your poor wan colleagues sitting several metres behind you in the artificial lights of the office? Will their biological clocks go into a tailspin? Not necessarily. For her doctoral dissertation at NTNU, Heidi Arnesen researched the best way to distribute natural daylight in an office or room. She has experimented with both full scale rooms, and on models.

“By using different systems we can change the direction of the daylight, so some of it shines further into the room”, she says.

Light catchers

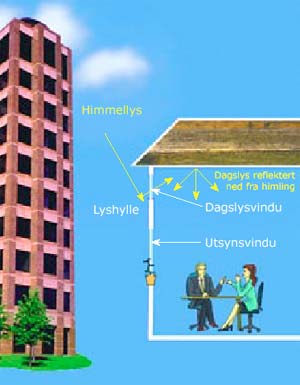

Two of the most common daylight systems are light shelves and glass or acrylic prisms. Shelves typically have a mirror coating and prisms are made of a translucent material.

A half-meter-wide light shelf can be attached horizontally to a window, so that it divides the window in two at about the height of our heads. The system captures some of the vertical light that is normally diffused into the room. The light that hits the shelf can be reflected onto the ceiling, where it then can be reflected down into the room.

A prism works in much the same way: The facets are designed to change the direction of the light. How much more light can be reflected into the room depends upon a variety of factors, including the amount of obstruction in front of the window. If a window has a clear view of the sky, a prism can increase the light as much as 50 percent.

A half-meter-wide light shelf can be attached horizontally to a window, so that it divides the window in two at about the height of our heads.

“The taller the buildings that face the window, the more a light shelf will increase the relative amount of daylight. The increase can be as much as 200 percent. But if the blocking angle is greater than 40 degrees, it can be impossible to create good daylight conditions”, Arnesen says.

The development of daylight systems is still in the experimental stage, so Arnesen doesn’t know how much an installed system will cost. One thing seems certain, however: an office that gets more natural daylight will need less artificial light – an improvement that can cut electric bills.

By Elin Fugelsnes