Into the mist

About 40 million people worldwide have dementia, and many more will continue to be diagnosed in the future. How should society meet this challenge?

THE FACTS: Every year, 9 000 Norwegians are diagnosed with dementia. Sixty per cent of them have Alzheimer’s disease. Many older people are never assessed for dementia, so the real numbers may actually be higher. The Norwegian health care system has relatively limited numbers of geriatric specialists. At the same time, the ageing population and the need for physicians with knowledge about dementia and complex age-related illnesses will increase dramatically in the coming years. Dementia generally cannot be cured.

Dementia is increasing dramatically around the globe and could soon be the most widespread and serious disease afflicting the global population. At the same time, researchers are racing to better understand the disease and find more effective drugs and treatments.

A FRIGHTENING DIAGNOSIS

Dementia is a catchall term for many brain diseases, the most common of which are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy Body dementia. The largest group is comprised of those with Alzheimer’s disease (60 %). The second largest group is vascular dementia, caused by poor blood flow due to blood clots in the brain or widespread atherosclerosis.

Source: Wikipedia. Photo: Scanpix Denmark

“If we can delay onset by just five years, the number of people with dementia may be cut in half, based on figures from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. The prevalence of dementia increases significantly after the age of 80.

Many people will not live long enough to develop the disease,” says Ingvild Saltvedt, who teaches and conducts research on dementia at NTNU‘s Faculty of Medicine.

In the meantime, people with dementia require considerable help and nursing care. But perhaps we should start rethinking every aspect of care for those with dementia. Should we consider dementia a disability that is due to an illness, in line with other chronic diseases and disabilities, which would give patients rights to individual treatment, appropriate aids and special arrangements?

A dreaded diagnosis

“Dementia is an unwanted and dreaded diagnosis for which we should have the greatest respect. It means a change in one’s overall life, as well as changes in everyday life – at first gradually, but eventually radically. It can be a daunting and sometimes lonely life. But it is not as grim as it is often portrayed. Many people live a long time with moderate cognitive changes, or find creative solutions to everyday challenges, and live well with the disease for many years. Some people put an emphasis on expression, joy and positive interactions in a more deliberate way than before their diagnosis. Some concede that their intellectual abilities are not what they once were, but at the same time can say that they have never thrived as much before they became ill. Much depends on how the individual handles the disease, and how the world relates to dementia,” says Kjersti Wogn-Henriksen.

Wogn-Henriksen is a psychologist at Molde Hospital, and has extensive experience working with dementia patients. She is now working on a PhD at NTNU, which addresses dementia patients’ self-understanding and insight into their own illness.

The study has a clear patient’s perspective and will highlight what it means to live with dementia: How do patients understand and experience their own illness? How do they try to live with the disease? What types of coping strategies do they choose?

The psychologist has closely followed a group of people with dementia over the past four years, and has studied how they have grown and changed with respect to the disease.

Most people know

“I see that there are large individual differences. But most people seem to understand and accept that they have dementia. The challenge is to acknowledge that you have the disease and comprehend what that means, while at the same time, within certain limits, to create as rich a life as possible. Even though an individual may have problems related to dementia in some areas, that person can also be competent in other areas. An increasing number are happy to go hiking. One person loves fiction and enjoys reading, although she immediately forgets what she has read. Most say they manage to take one day at a time; they don’t get obsessed about the future, and are good at emphasizing the positive. Some say they experience a phenomenon we see in others with serious diseases: they are reminded of what is important in life,” says Wogn-Henriksen.

She adds that the people who are the happiest are those who are active and adaptable, have something with which to occupy themselves, and have managed to come to terms with new ways of existing in the world. They are not passive victims of their disease, but show a great willingness to learn and an ability to adapt. And it’s not just a matter of an individual taking steps to live with dementia, but also relationship-based coping, where interactions with one’s spouse, family or professionals are important.

GLOOMY FORECASTS

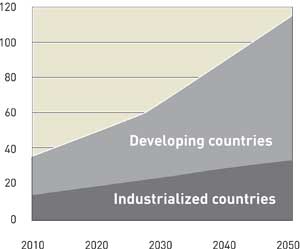

The graph shows the expected increase in the worldwide number of those with dementia. Today, about 40 million people are diagnosed with dementia, but that number could rise to 120 million by 2050. The trend is increasing, as the population gets older. Accordingly, the largest and most dramatic

increase in dementia is found in developing countries, as lifespans increase.

Source: Alzheimer’s Disease International

The study also shows that there are gender differences: “It appears that women are more likely to adapt to and cope with their new lives. In nursing homes, we see that women want to join around a table and enjoy each other’s company. The men keep more to themselves. Women always have some little hobby that they can occupy themselves with, while it may be more difficult to motivate men.

The difference may be because men, to a much greater degree than women, place emphasis on the ability to perform, to be self-assertive and independent,” she notes.

Findings from the freezer

But why and how is the brain damaged in dementia – what goes so terribly wrong? So far, virtually every new discovery related to the disease has led to more questions than answers.

A huge warehouse at the HUNT Biobank in Levanger is jam-packed with freezers holding blood samples and DNA material from thousands of residents of the county of Nord-Trøndelag, north of Trondheim. This material is used in medical research in many areas.

Perhaps there are secrets frozen here that could solve some of the many mysteries surrounding dementia?

In addition to biological material, there are MRI images of the brains of Nord-Trøndelag residents, and a whole host of other information about their health-related conditions.

HUNT (the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study) has been undertaken in three separate surveys over eleven years. The first was conducted in 1984–1986. Some of the participants in that first survey have now reached an age where they are at risk of developing dementia. This means that it is possible to find detailed health data for people who develop dementia fully 20 to 30 years before they show signs of the disease.

“We are now in the process of building a database where we assemble all of the information we have about participants who have received a diagnosis of dementia,” says Jostein Holmen, a professor at NTNU’s Department of Public Health and General Practice and until recently, director of HUNT.

“This dementia database makes it possible to compare all of the health-related information and material that we have for these patients. It can show whether there was anything special about them before they developed dementia. This is unique and can be a goldmine for researchers. We are not aware of any database like it in the world,” says Holmen.

Currently, the database includes people who have been assessed and have been diagnosed by a specialist in the last 15 years. The Health and Memory project involves collecting data from people who have been referred for assessment at the memory clinic, and patients with dementia in every nursing home in Nord-Trøndelag. Linking the results from these studies to data from HUNT provides unprecedented opportunities to identify early risk factors, different types of dementia, and additional symptoms of dementia, such as psychosis, depression and agitation.

The broad survey also provides valuable information about the prevalence of dementia, medication use, functional status, quality of life and physical illness among nursing home residents in Nord-Trøndelag.

RESEARCH DREAM

Dementia cannot currently be cured, but an intense research race is underway to develop drugs that can prevent and delay its development and reduce symptoms.

Photo: photos.com

The project has been undertaken in cooperation with the Norwegian Centre for Research, Education and Service Development Centre, Ageing and Health, among others. In the next round, Holmen wants to include the elderly living at home. The purpose is clear:

“We know that the number of elderly will increase, and we must prepare ourselves for it. We need to gather as much information as possible, and ensure that we create the capacity to address this situation in health personnel at all levels – especially in doctors,” says Holmen.

In his opinion, modern medicine is unilaterally focused on curing people, and is too unconcerned with relieving pain and providing care.

“We forget that providing care and relief from pain is the original humanistic tradition in medical science, and was prominent until the Second World War. Alzheimer’s is among the diseases that we cannot cure. It must be treated with other approaches and requires that doctors change their attitudes and give more of themselves,” says Holmen.

Dementia and depression

One of the individuals working with the dementia database is Eystein Stordal – who is also one of Norway’s few specialists in geriatric psychiatry. He believes that the database is a valuable source of new knowledge about the causes and risk factors for dementia, and believes that many disorders may predispose an individual to dementia.

“We already suspect that some of these illnesses are different types of what we call lifestyle diseases,” says Stordal.

For his part, Stordal will use health data from HUNT to conduct research on dementia and depression.

“During the early stages of dementia, the clinical picture is quite complex, and is challenging to diagnose. Often we have to address several diseases that occur at the same time – there may be a mix of problems, including cognitive impairment, and psychological and physical symptoms,” he says.

The main problems that are present in geriatric disease are dementia and depression, both of which occur at high rates and share very similar symptoms. This means that the symptoms are easy to misinterpret. ”This is unfortunate for several reasons. Dementia cannot be cured, but depression can be treated. We have both effective drugs and other treatments for depression,” Stordal says.

He adds that some brain studies of chronic depression and Alzheimer’s dementia show changes in the same brain area.

New diagnostic tools

Sigrid Botne Sando is a senior consultant at St. Olav’s Hospital, and a postdoctoral fellow at NTNU’s Department of Neuroscience. Her area of research specialization is dementia in general, specifically Alzheimer’s disease.

In connection with her doctoral work in 2008, “Alzheimer’s Disease in Central Norway: Genetic and Educational Aspects,” a biobank was established of blood samples from 600 Trøndelag-area residents with dementia and about as many healthy, older residents from the same region. The project is called Tronderbrain.

Sando and her research group used the material to study a well-known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, APOEε4.

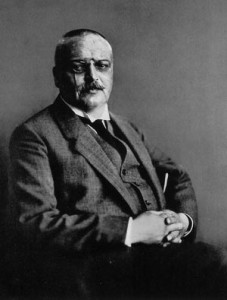

Discoverer

Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), a German physician, psychiatrist, neurologist and neuropathologist, was the first to identify the symptoms and the histological findings of what is now known as Alzheimer’s disease. He observed the disease in a patient in 1901. When she died five years later, Alzheimer examined her brain and found distinctive changes.

Photo: Wikipedia

APOE is a gene carried by everyone, and comes in several variations, called alleles. The most common variants are called ε2, ε3 and ε4. Everyone has two alleles, one of which is inherited from his or her mother and the other from his or her father. All combinations are possible. The APOEε4 allele increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, with the risk even higher if you have inherited APOEε4 alleles from both parents. However, it is not necessary or sufficient to not have the APOEε4 allele to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Sando’s investigation of this genetic risk factor is the largest ever conducted in the Nordic countries. She found that the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease increases by a factor of 4.3 if you have one of the risk-related alleles.

If an individual has inherited a double dose of the ε4 allele, i.e. from both parents, that person is about 13 times more likely to develop the disease as individuals without the variant at all. This is consistent with findings in similar populations elsewhere in the world.

Education helps

In her doctoral thesis, Sando also examined the Tronderbrain material to see how education and schooling related to the development of Alzheimer’s disease. International studies have shown that the risk of Alzheimer’s is higher in populations with little education. Sando also found that there was a correlation between the risk of Alzheimer’s and the number of years in school. The more education – the lower the risk.

“In other words, it looks like it is good to use the brain, just like muscles. One explanation is that education/use of the brain may contribute to the formation of new synapses (connections between nerve cells), so that the brain has ‘more to go on’ when the disease strikes. Other studies have also shown that physical activity reduces risk with respect to Alzheimer’s disease,” says Sando.

She is now a postdoctoral researcher, working again with the collection of material from Trondheim-area patients who have mild cognitive impairment and patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, as well as from healthy, same-aged control subjects. Both blood and cerebrospinal fluid from patients and control subjects have been collected.

“The main purpose of the project is to look at biological markers for Alzheimer’s disease. Biological markers (biomarkers) can be used in diagnosis, in developing a prognosis and to assess the efficacy of drug therapy. When we have more effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, it will be important to be able to make the correct diagnosis at an early stage of the disease so that treatment can be started as early as possible,” said Sando.

The collection of biological material will extend until 2014, but the analysis of the material is likely to continue beyond that date.

The race to find answers

Researchers have also identified two proteins, amyloid and tau, which are involved in the process of destroying the brain.

The proteins clump together and create insoluble tangles, which first create errors in the biochemical signal transmission between nerve cells and subsequently lead to cell death.

Researchers at NTNU’s Department of Physics are conducting on-going experiments that should help clarify the processes that take place in the brain. In cooperation with Linköping University, Professor Mikael Lindgren has developed custom-designed molecules, called probes, which can be sent into the brain through the blood stream and literally light up what goes on inside there. A previous article in Gemini about Lindgren’s work, called Secrets of forgetting, was published in September 2008.

In short, the mission for the probe is to recognize the special structures of proteins that destroy brain cells in Alzheimer’s dementia. The proteins are associated with various stages of the destruction process. When the probe enters the brain, it will look for the different proteins and attach to them.

The probe’s journey towards its goal can be followed using a laser light. Once it has attached itself to the protein that it has been looking for, the laser light changes colour.

GARDEN FOR HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

A sensory garden for those with dementia has been designed and adapted specifically for this patient group’s needs. The garden is often linked to a day-care centre or nursing home, and aids residents by stimulating all their senses. The Norwegian National Centre for Ageing and Health has established eight test gardens across the country.

Photo: City of Bergen / Bernt A. Tungodden

The different colours tell researchers which proteins are found in the brain, so they can determine how advanced the disease is.

“We have made great strides since the last time you wrote about the project,” Lindgren tells Gemini. “When we last spoke, we had managed to make just two probes, but now we have 15. This means that we can find 15 different protein structures. We have also succeeded in making fluorescent probes and magnetic probes. This means that the probes can be imaged using MRI, which provides completely new opportunities.”

Lindgren hopes that the probes and the technology behind them can be used as a diagnostic tool for different stages of Alzheimer’s. Then it may be possible to detect the disease at an early stage.

“We are much closer to a tool that can be used on humans. Currently, we have experimented with mice,” he says.

Confusion in the archive

Lindgren is planning to work with Menno Witter, a professor of neuroanatomy and a scientist at NTNU’s Centre for the Biology of Memory, about possible applications for the probes.

The centre collaborates with researchers around the world to understand the brain region called the hippocampus, which is involved in memory and learning. Several types of dementia begin in this area.

Understanding what is going on in a healthy brain is a prerequisite for understanding pathological conditions. Witter’s project concerns the changes taking place at the very beginning of the long process leading to Alzheimer’s disease, and understanding how the memory network works.

He explains that the hippocampus acts as an information centre, which receives information from sensory inputs and sends it further around the brain, where it is stored as memories.

“We can imagine that the brain is like a filing cabinet, which has separate drawers for pictures, taste, smell and hearing – all the elements we need to form a complete memory of an experience,” Witter says.

All of the file drawers are related to each other, he explains. The memory of an image can be turned on and awakened by the perception of a voice, a melody or a smell. If we pull out a tray for smells and think of the memory of the scent of a rose, it may be associated with other impressions that were stored at the same time, which would call up the memory of a certain garden party, for example.

“To recall the memory of this interview, it may be enough for you to simply hear the sound of my voice. But to remember the whole thing, you have to call up a great deal of information about the details: how did I look, what did I wear, what did the room look like, how we were positioned in the room and so on,” Witter says.

One of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s is the inability to store new memories, and that similar memories interfere with each other and blend together. This is seen in the hippocampus and the adjacent paracampus.

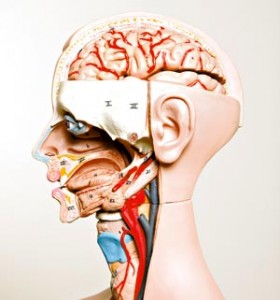

WHY THINGS GO WRONG

NTNU’s Centre for the Biology of Memory is working to understand the hippocampus, the region of the brain that is involved in memory and learning. All types of dementia start in this area. One of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s is the inability to store new memories, and a problem with similar memories interfering with each other and blending together. This occurs in the hippocampus and the adjacent paracampus.

Photo: Geir Mogen/NTNU DMF

Something goes wrong in the network that connects the different brain areas and the various “file drawers” with each other. The problem causes the network to collapse like a house of cards, but why? In order to store new memories the brain must reorganize itself. Is this the process in adults that can cause someone to develop dementia? This is one of the questions that Witter hopes to answer.

Meditation and grey matter

Dementia research takes many different approaches, and new discoveries add new pieces to the puzzle. For example, a recent study from the University of Tromsø suggests that there may be a connection between dental health and the development of dementia. Other theories have not come farther than the thinking stage. For example, there is some speculation as to whether meditation can have a preventive effect on dementia.

“It has not been possible to find any direct evidence that meditation provides a dampening or braking effect on the development of dementia,” says Are Holen. He is a professor of psychiatry at NTNU and founder of the Acem organization for meditation.

However, there are numerous studies that show that the thickness of grey matter in the brain increases in those who meditate. The change can be seen after a short time. Even after eight weeks, it has been demonstrated that parts of the brain are thickened in those who have begun to meditate.

It has also been shown that the thickness increases relatively more in the elderly than in younger individuals.

The age-related reduction in the thickness of grey matter is less in those who meditate, in some parts of the brain. The parts of the brain where these changes take place are central in the development of dementia.

“That means it is possible to assume that meditation can reduce or stop dementia, but it has not been proven that it really does so. But the findings are interesting and may point in that direction,” says Holen.

The importance of olfaction

PhD candidate Grete Kjelvik at the Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging studies how olfactory stimulation affects activation patterns in the brain. The method she uses is called functional MRI (fMRI), and her study includes patients recruited from the geriatric outpatient clinic at St. Olavs Hospital, as well as healthy elderly control subjects.

In an fMRI investigation, the brain is imaged while the subject is inside the MRI machine and is performing a task – in this case, a task related to the sense of olfaction.

“In this way, we can see where there is activity in the brain while the subject smells something,” explains Kjelvik.

Kjelvik is examining the fMRI images that are generated from the patient groups while they use their sense of smell, to see if there are differences from the healthy control group.

“There are areas in the temporal parts of the brain that are activated by olfactory stimulation, and the degenerative process in Alzheimer’s disease is thought to start in the structures of the temporal lobe. A number of international studies have shown that Alzheimer’s is associated with hyposmia, an impaired sense of smell. In this way, the link between olfaction and memory is very interesting,” says Kjelvik.

Into the mist

Not so very long ago, dementia was surrounded by taboos and shame, and was something you would rather not talk about. The taboos are still there, but are lessening as people learn more about the illness. In the past there have been efforts to educate the public, both by officials and by private individuals.

A leader in this area is Ola Hunderi, a physics professor at NTNU.

“Seeing a loved one slowly melt away from you is not easy. It weighs you down with a grief that is impossible to describe. She’s still here!”

The quotation is taken from ”Into the Home of the Mist”, the book Hunderi has written about life with his wife Inger Anne, who as a 55-year-old was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Here he describes candidly the insidious symptoms at the start and her slow evolution into becoming fully dependent on others.

“All her ability to communicate and move was gone. The last form of contact was through her eyes. In rare and brief glimpses, I was

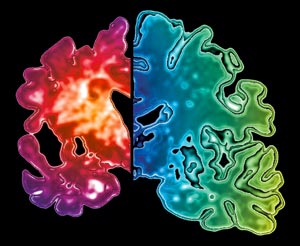

Cell killers

Two proteins, amyloid and tau, work together in Alzheimer’s disease to destroy the brain. The proteins clump together and create insoluble tangles. This creates errors in the biochemical signal transmission between nerve cells, and subsequently leads to cell death.

Photo: Science Photo Library/Scanpix

convinced that there was someone in there. No one can know how the patient experiences this phase. I speculate that dementia may not be the worst end of life … Maybe it is worse to die of cancer with excruciating physical pain,” Hunderi says.

The resourceful professor was able to take on his wife’s care until late in the disease. When his wife finally got a place in a nursing care facility, he moved into the same room.

“It was a win-win situation for both us and the health professionals,” he says. “For Inger Anne, it made the move less dramatic, and she felt safer having me there. Despite the circumstances it helped to normalize my life. I could do my work and could do things more freely, without fear of what might happen at home. I was assured that she was in good hands. And the nursing staff got welcome relief.”

Hunderi is upset that most media stories about caring for those with dementia are horror stories and descriptions of abject misery. “I was witness to an impressive effort that gave me an insight I never will forget,” he says about the experience.

Psychological pressures

Inger Anne Hunderi had what is called early onset Alzheimer’s. Its symptoms are similar to the more common version of Alzheimer’s, which occurs in the elderly, but the disease can sometimes progress much faster.

Early onset Alzheimer’s represents a relatively small category of dementia-related diseases. Yet it is this variation that we hear and read most about. It may be because resourceful individuals like Hunderi stand up and share their personal experiences. He travels far and wide to give talks and is always willing when someone wants him as a speaker.

In his book he makes it clear that it is not only the patient who is affected by a diagnosis of dementia. Life also changes radically for any partners.

That fact is important, because more than half of all elderly patients with dementia live at home, and that figure is expected to rise. Most people want to live at home as long as possible.

This aspect of dementia care is largely unexplored, and there is little literature on the subject.

Bente Nordtug is a nurse specializing in dementia disorders who defended her PhD in June 2011 at NTNU’s Department of Neuroscience. She studies the burden of care for the one partner when the other partner gets dementia and continues to live at home. As far as she knows, no one has done similar studies in Norway.

Nordtug has come up with several sobering findings – among other things, that 60 per cent of the people who live with individuals with dementia have a high incidence of psychiatric symptoms.

“If they had been examined by a psychiatrist, they would have been given one or more diagnoses,” Nordtug says.

Her investigation includes different stages of the dementia process. She has found that the impact is relatively modest at first, but increases rapidly as the disease worsens. The less self-reliant the ill person is, the greater the impact.

“In cases where the dementia is aggressive, the burden of care is even greater. There is much to suggest that affected families reach far, often too far, in trying to offer care, and that they look for nursing home places too late,” she says. “This is unfortunate for several reasons. First, because there are long waiting lists and it is hard to get a place. This increases the wear on the caregiver, who is already exhausted. And patients with more advanced cases of the disease find it harder to adjust to the new surroundings.”

Gender and Care

The study shows interesting gender differences in what affects the burden of care among relatives.

“It seems that men put most emphasis on the need for breaks, with time for themselves. It means a lot to them that their partner can be left alone for a number of hours, or that he gets help, and a break from having to provide care. But uninvited help is experienced paradoxically as a burden. The men in the survey want to ask for help themselves, and want have control over the situation. Even if friends and family pull away, this has little impact on the burden of care for men,” says Nordtug.

She finds that the picture is quite different for women. Women find it difficult that family, friends and neighbours keep their distance. This type of withdrawal is common. It may be due to the fact that dementia carries a stigma, but also due to the fact that close friends and family simply do not know how to cope, what to say and how they can be of help.

“Women talk a lot about the loss of having someone to discuss things with, to hug, share feelings with, to do things with. They want a response to their emotional reactions and see this as positive,” says Nordtug.

“The women’s approach is to ask ‘How do you do that?’ They are out there, finding out what works well and what doesn’t, reflecting on why things work and are constantly evaluating the situation. They have a wait-and-see attitude, and try to fend for themselves as long as possible. It is common for women to wait longer than men in similar situations to seek a place in a nursing home or care facility,” she says.

It would seem that Nordtug’s findings reflect traditional gender role patterns: women react emotionally, men are more rational. This may be one explanation for why men seem to get help more quickly from the system of care when they ask for it.

Nordtug believes that the strengths and weaknesses of the gender differences she has found should be exploited in a positive way: “The conclusion is that family members who provide care are an important group to educate and support, and that this should also be emphasized in the training of health care workers.”

Technology for dementia

Many believe that new technologies will give people with dementia a better life. Others are afraid that technology could be used as a crutch and will reduce patient access to human contact and care.

One of the most difficult discussions centres on equipping people with dementia with tracking tools such as GPS. Sceptics frame the discussion around ethical issues, and are concerned about privacy, among other issues. Supporters believe that it is more important that GPS can give people with dementia greater security and a better quality of life, because they will be able to move more freely.

SINTEF is involved in several projects related to technological aids for people with dementia. One of them relates to social media. The project has as its starting point the fact that social media are playing an increasingly important role in modern society. Social media are important venues for social contact and communication. This creates new opportunities for how we interact socially.

Older people with dementia are groups that traditionally have not used computers and social media. By customizing and adapting the technology, it may also be possible for this group to use social media.

A project called Alma’s House is designed to examine how assistive technology and well-being technology can be integrated into a larger holistic programme of care for people with dementia. This research is being conducted in collaboration with the municipalities of Drammen, Bærum and Oslo, along with Livework Nordic AS.

A pilot project will be launched in 2011 in partnership with the City of Oslo, SINTEF, the National Centre for Ageing and Health, the Oslo University Hospital and the Department of Computer Science at the University of Oslo.

Someone who cares

Psychologist Kjersti Wogn-Henriksen is a strong advocate in arguing that society must open up and become more inclusive and generous to people with dementia. This would make it easier both for those who are ill as well as their relatives.

Experience suggests that quality of life increases with the degree of openness.

“Those who are able to talk openly about what it is like, gain more space in which to live and move. But it is not always easy in a society that values the ability to be quick and dynamic and intellectually productive,” says Wogn-Henriksen. “The opposite approach is to try to keep the illness hidden and struggle to live life the same as before. For these people, the feeling of powerlessness must be great, and I fear they live a lonely life.”

The psychologist hopes that her PhD thesis will help to shake up some old prejudices and provide a more nuanced view of dementia as more than just an assemblage of deficiencies.

“There is a real need to change attitudes, based on knowledge and understanding and a willingness to see the individuals behind the dementia. And we have to have a different perspective on care. What is forgotten is uninteresting. What is important is what is remembered, what is still perceived as meaningful, and if there is someone who cares,” she says. “To have dementia is not the same as ceasing to live as a human being.”

By Synnøve Ressem