Choking on their own growth

The population of the world’s cities is growing by 60 million people a year. What can urban planners do?

KEY FACTS: The world’s cities are growing faster than ever, and most rapidly in developing countries. Almost the entire global population increase over the next decades will take place in the cities of the south. The population in cities has increased fivefold since 1950, increasing by 60 million a year, according to UN figures. This kind of growth is the equivalent of adding a city like Trondheim, with its 170,000 residents, to the population of cities – every day. By 2050, there will likely be well over nine billion people on Earth, 70–75 per cent of whom will live in cities.

Cities have grown rapidly before: Consider London in the 1900s, or New York just after the Second World War.

Urban planning in the south

Urban ecology as a discipline goes back to the 1980s. Since then, a large number of students and teachers from NTNU have travelled to developing countries to study urban design and planning there.

Photo: Haining Chen

But London took 100 years to grow from one million to nearly ten million inhabitants. Asia and Africa’s major cities will grow much faster than that. The population in cities such as Lagos, Delhi, Mumbai and Dhaka is increasing by more than 300,000 residents a year. In a few decades, Mumbai is expected to become the world’s largest city, with more than 35 million inhabitants. Over half of them will probably live in informal settlements, known more commonly as slums.

Is it possible to plan, if not control, these developments? Or will these 21st century megacities choke on their own growth?

Two visions

Great, says the optimist. Strong, vibrant cities have always been synonymous with economic, social and cultural growth and development. Cities make it easier to provide basic services such as water, education and health in than in the countryside. Urban development has helped lift millions out of poverty.

But the pessimist points out that sprawling cities, which expand unchecked and ever outward, greedily gobble up soil and water and other scarce resources. Cities are divided, socially and geographically, where the wealthy wall themselves inside protected enclaves and the rest of the population is left to fend for itself. These same cities make a huge contribution to increased CO2 emissions, adding to climate change that will cause problems for the poor.

No more rural Africa

We’ll come back to all that. But first let’s go to Africa, and the Ugandan capital of Kampala. Africa is the world’s least urbanized continent – but that is about to change. Africans are flocking to cities at a pace no continent has seen before. In 1950, all of Africa’s cities combined had a population of 33 million. But that number may grow to as much as 1.3 billion by 2050, according to estimates from the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, also called UN-Habitat. That means a 40-fold increase over 100 years.

Uganda and Kampala are no exception. Uganda’s population of 35 million is expected to triple by 2050. That could mean an increase in the capital’s population by five-fold at the same time.

“I once asked the Minister for Urban Development in Uganda about how they prepare for this growth. They do not,” says Hans Skotte, an associate professor in NTNU’s Department of Urban Design and Planning.

“Urban planning in the south has been a disaster at times. The way it has been conducted, it has either been useless or downright harmful,” he says.

Unprepared for growth

“I once asked the Minister for Urban Development in Uganda about how they prepare for this growth. They do not,” says Professor Hans Skotte.

Photo: Anne J. Bruland

Traditional planning can be problematic because it does not take into account how the majority of the residents in rapidly growing slums actually live, thus contributing to their marginalization and increased divisions between rich and poor, to paraphrase the UN-Habitat programme.

“This is a problem in countries with weak institutions where laws are ignored. Plans are made, but the countries lack the resources to implement them, both from a personnel standpoint, and financially. Corruption leads to enormous waste. Traditional Western planning is impossible. We have to find other approaches,” adds Skotte.

Dumped in the slums

When traditional top-down urban planning does not work, what do you do? That’s exactly what a group of NTNU students who were dumped in the Kisenyi district in Kampala last autumn had to figure out. Kisenyi is a slum of about 25 000 inhabitants, located in central Kampala.

Here, students in NTNU’s urban ecological planning course conduct a two-month-long field study with a challenging mandate: Find out what’s happening in the area, what makes the wheels go ‘round. And based on that, find a project that will benefit the people who live there, and that can be implemented.

“It was the first time I had encountered Kampala, and everything seemed chaotic,” said Ida Mosand.

Mosand, an architecture student, took urban ecological planning as a semester course.

“The message we were given when we arrived was to go out and make ourselves known. No one really told us what we should do, what we should contribute. We had to find out for ourselves. So in the beginning I felt lost, I didn’t understand what I was doing there,” she said.

Fellow student Daniel Kaddu is from Kampala. He was educated as an urban planner at Makere University in Kampala, and is taking his master’s degree in urban ecology at NTNU. But he had never been in Kisenyi before. He had the same initial reaction as Ida.

Local resources

“Instead of asking what does not work, we have to start with what they can get,” says Professor Hans Christie Bjønness, NTNU.

“Everything seemed chaotic. And I thought like a traditional urban planner, with ready-made solutions to what I perceived as the main problems. But what we first thought was most important to people in the area, proved to be far down on their priority list. Their top priority is more secure property ownership and tenancy,” says Kaddu.

Build something nice…

“When we first went around the area, we saw lots of open space,” Mosand said. “We thought that maybe we could help to build something nice in these areas – a playground or something. But we quickly found out that the open area was from a house that had been recently demolished. Hundreds of people had been thrown out into the streets. This kind of uncertainty was everyday life for most people. Why they should devote time and money to improve the local environment, if they risk being thrown out the next day?”

“Ownership is often unclear,” said Kaddu.

Landowners who want to earn a lot of money often choose to sell to property developers who mow down existing houses so they can build something new and more lucrative, Kaddu said.

“Some of us almost got beaten up when we walked around, because people thought we were investors who were buying up property,” said Mosand.

To make a long and complicated story short: the NTNU students worked on two projects with a local organization and students from Makere University, which involved increasing the housing density of residents and moving people to a new area. The objective of both projects was to give people safer living conditions.

“These were the residents’ own solutions. Our role was to provide professional knowledge,” Mosand said.

Interaction

World’s youngest capital

A Norwegian architect team is participating in the UN-Habitat program in Juba, the new capital of war-torn Southern Sudan. The city spreads uncontrollably in areas without infrastructure, and without people being permitted to settle there. In cooperation with local authorities, architects are developing planning tools, with the hope of creating a joint architecture educational programme with Juba, Oslo, Trondheim, the Norwegian Refugee Council and UN-Habitat. The team consists of Anna Skibevaag, Sigrid Vesaas and Sven E. Svendsen, all of whom have connections to NTNU.

Photo: Anna Skibevaag

The methods the students used were different from what Daniel Kaddu had learned when he studied urban planning at Makere University.

“The big difference is the interaction with people. You have to talk to people to figure out the core issues. It’s time consuming, but it also makes it much more likely that the plan will actually be implemented,” said Kaddu. He will return to his teaching job at Makere University in Kampala to share his new insights.

The government and politicians have to be involved in these interactions, he stressed. And the government must accept and recognize the informal sector.

“Before I went to Kisenyi, I thought of informal settlements as something that had to go. That view has changed. Kisenyi is a city within a city, with its own social networking and jobs,” he said.

Sixty per cent of the jobs in Kampala are in the informal sector. Without this activity, the formal economy simply wouldn’t work. If we tear down slums, we only create new problems: People lose not only housing, but also employment and social networks. This kind of planning creates criminals before the night is over.

Insight, knowledge, confidence

Hans Skotte travelled to Kampala with the students as their teacher. Or, as he says himself: Someone had to take on the boring job of organizing and money issues. As for teaching – the students teach themselves.

“They were self-motivated and learned from their own decisions. It’s not enough to have knowledge, insight is equally important – an understanding of what is happening, why and how. Without that, knowledge is worthless,” he said.

Skotte and some of the students were back in Kisenyi in the spring, to open an exhibition that showed the results of their efforts, including a full-scale model of a residential unit for slum dwellers, which the students hoped would be built as a multi-storey complex.

“The event was inaugurated by the home minister. We were on national television on several occasions, and in the press, both in English and in the Luganda language. We were on the national and local radio. Pretty exciting,” Skotte wrote in an enthusiastic email from Kampala.

“There are plenty of idealized models that arise from well-meant, but misguided, attempts to plan a way out of the problem. What we did was to go to the level of the people who actually had housing problems while simultaneously implementing solutions. But they cannot do it alone. They must be supported by strategic public housing initiatives. That’s what we tried to show,” he said.

“The solution is thus either bottom-up or top-down,” said Skotte, and described what he calls a bottom-top perspective: Those at the top need to ensure that those at the bottom can use their own resources. But that requires confidence in the government.

“Without these kinds of connections, and this confidence, we’re stuck in a vicious circle, where world development organizations offer good suggestions, while inequality grows, and distrust and corruption continue,” he said.

Building on local strength

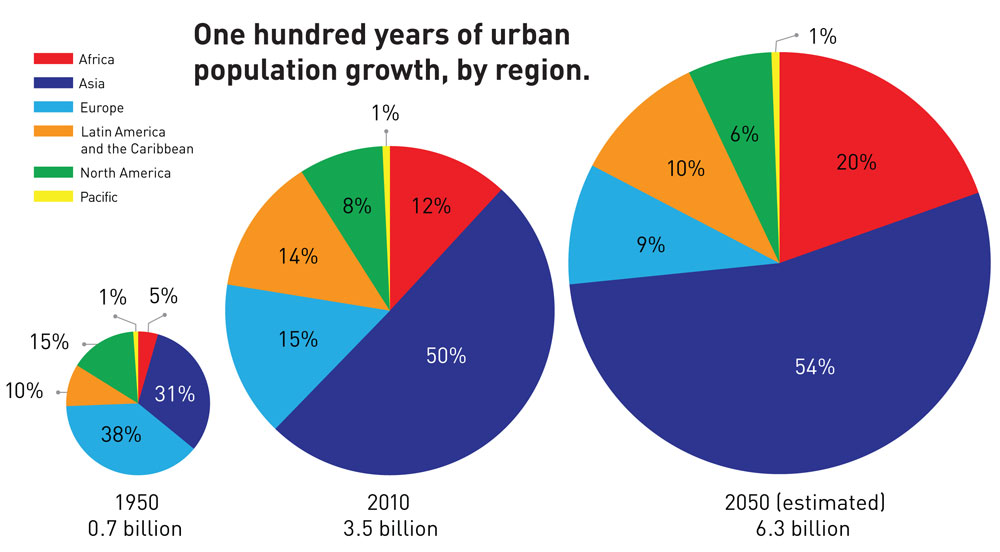

• In 1950, the world’s cities had 700 million inhabitants, 53 per cent of which were in Europe and North America.

• In 2010, 3.5 billion people lived in cities, half of them in Asia.

• In 2050, the world’s cities are likely to have 6.3 billion residents, according to UN estimates. Fifty-four per cent of them will live in Asian cities and 20 per cent in Africa. Europe and North America’s share of the world’s urban population will have dropped to 15 per cent.

Source: UNDESA

Methods that were first used in Kathmandu have been proven over time. The Urban Ecological Planning programme dates back to the 1980s. Hans Christie Bjønness, a professor in the Department of Urban Design and Planning, NTNU, travelled with two colleagues and six students to the Nepali capital of Kathmandu to study informal, unplanned settlements.

“We started with the traditional formal data. Those data showed that people living in Kathmandu’s slums actually should not have water at all. So instead of paper studies, we went out and asked people how they got the water they needed. That enabled us to use their own solutions as the basis for improvement,” Bjønness said.

The same approach has been used in other areas.

“Instead of asking what does not work, we start with what they have, and build on local resources. We have to build on their strengths, not their weaknesses,” says Bjønness.

There have been many trips back to Kathmandu, and later to the slums of Delhi with both Norwegian and foreign students. In 1999, Urban Ecology became the first international master’s programme in the Faculty of Architecture. Most students come from developing countries.

The programme works with Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, the College of Architecture in Delhi and Makere University in Kampala. The University of Tibet is also involved in a collaboration on a multidisciplinary doctoral programme, which includes NTNU’s Department of Hydraulic and Environmental Engineering and the University of Kathmandu.

“Thus, we have also contributed to South-South cooperation between Tibet and Nepal,” Bjønness says.

NTNU is a partner university with UN-Habitat, which has as its main objective to promote sustainable urban development. NTNU admin- istrators have also discussed the possibility of making sustainable urban development into one of NTNU’s multidisciplinary strategic areas. There are certainly enough issues to address, whether dealing with water, transport, buildings, health, planning or policy. It is perhaps precisely the combination of these disciplines that can contribute to some technological and social development advances.

“This is about our social contract as a university. And our moral responsibility to promote development that balances social, economic, cultural and environmental issues, not just for now but for future generations,” says Bjønness.

Sustainable – for all

Perhaps most importantly: Sustainable urban development must involve everyone, not just a wealthy minority living in well-planned, green oases, surrounded by visible and invisible walls that block out the unwashed masses.

The optimist we first met at the beginning of the story was right: Throughout history, growing cities have been synonymous with economic activity and growth. The greater the degree of urbanization, the stronger the economy. Europe and the US have an urbanization rate of nearly 90 per cent. China passed the tipping point of having 50 per cent of its population as city dwellers in January 2012 and will probably exceed 70 per cent by 2050.

People go to cities and towns to find happiness, or at least a job. It is in cities where they can meet others and form networks that provide the foundation for innovation. The old rule that increased urbanization means economic progress still applies, UN-Habitat said in its 2010/2011 report on the state of the world’s cities. Even in most slum areas, people have larger incomes and are able to consume more than in the villages they left.

WHAT IS A SLUM?

UN-Habitat defines slums as a household that lacks one or more of the following:

• Access to sufficient clean water without spending a disproportionate amount of time and effort to obtain water.

• Access to sanitary facilities, either in the form of private toilets or a public toilet shared by a reasonable number of people.

• Security in ownership or tenancy. Documentation that provides secure housing, and protection from eviction.

• Housing of adequate, permanent quality, built in a place that is not dangerous for residents and that protects inhabitants from rain, heat, cold or moisture.

• Adequate living space. No more than three people to each room.

Photo: photos.com

Divided cities

While nearly everyone likes the prospect of increased prosperity, UN-Habitat warns of a trend toward divided cities, where a large part of the population does not have access to basic services such as water, health, education, housing.

From 2000 to 2010, the proportion of people living in slums decreased from 39 to 32 per cent. More than 200 million people have better housing, water and sanitation, mostly in China and India, the UN-Habitat report estimates.

While this sounds like good news, the probem is the population in cities has increased so much that in absolute terms, the number of slum dwellers has actually increased, even though the percentage is reduced. Without much stronger measures, nearly 900 million people will live in slums in 2020, the UN-Habitat report says.

The United Nation’s children’s fund, UNICEF, focused its 2012 report on children in cities. These children have generally better health and are better educated than their peers in rural areas, the statistics show. But average figures camouflage differences within the cities. Where there is more detailed data, the numbers show the huge differences in children’s chances of survival, in nutrition, health, educational opportunities and access to other services. The increasing number of children who grow up in informal settlements are deprived of access to basic services to which they are entitled, the UNICEF report says.

Social and geographical fragmentation is accentuated when cities spread out in an uncontrolled manner over large areas. Uncontrolled sprawl is now a global problem, and is a symbol of the divided city, the UN-Habitat report says.

“Internal inequality is a major cause of many problems in rapidly growing cities, when it comes to health, safety, transportation and other infrastructure,” states Skotte.

Rights are key

It’s essential that the rights of poor people in slum cities are recognized and respected if we want to slow the progression toward sprawling, divided cities. Investment in basic infrastructure is also necessary if urban growth is going to contribute to economic prosperity, says Rolee Aranya.

Aranya is from Delhi but is now an associate professor in NTNU’s Department of Urban Design and Planning.

Half of Mumbai’s 15 million inhabitants live in slums. But they occupy only five per cent of the land area. They are easily overlooked in the city planners’ land use plans.

“Traditional top-down planning does not solve the problems of the informal sector. The core issue is land rights. Too often slum dwellers are left to themselves. This just maintains and reinforces inequalities,” she says.

The Dharavi district in Mumbai is Asia’s largest slum. A project was launched to build high-rises for people who lived there, using public-private financing.

“But the offer was effectively only for individuals who owned housing. The many people who were only tenants had neither the financing or right to move in,” says Aranya.

Formalizing the informal

If there is to be any hope of gaining control over development, and make life more liveable for slum dwellers, governments will have to accept informal settlements. They need to find a way to formalize informal, undocumented forms of property. They must also invest in social institutions and infrastructure such as water and sanitation.

“There are positive examples, such as in Brazil. Public investment and formal rights for the residents of favelas also mean that they can actually risk investing in their homes,” says Aranya.

Curitiba in southern Brazil has invested aggressively in public transport from informal areas on the outskirts of the city. This investment helped create more jobs, because people can come into the city, while at the same time this has reduced CO2 emissions. Venezuela has made public investments in poor informal settlements in places, which has led to the investment of local resources and activities that contribute to improved living conditions for slum residents.

VULNERABLE TO FLOODS

• Climate change could force 200 million people to flee by 2050.

• In coastal cities in North Africa, a temperature increase of one to two degrees will expose 6 to 25 million people to an increased risk of flooding.

• By 2070, the vast majority of the most flood-prone cities will be found in developing countries, particularly China, India and Thailand.

• Today, 40 million people live in areas inundated by so-called one hundred year floods. By 2070 that number will increase to 150 million.

Photo: Hans Skotte

“This creates a kind of partnership between the government and residents. But everything is related to rights,” says Aranya.

But slum dwellers will not get their rights for free. They must fight for them. But here things are also happening. Slum dwellers themselves are coming together in many cities and organizing to create their own solutions. An international network, Slum Dwellers International, has also been organized to bring together local organizations for slum dwellers in 33 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

“The traditional solution, to mow down shanty towns with a bulldozer, is not as politically possible as it once was. Plus there are many slum dwellers, so they have the ability to be a political force. Many political parties in India are competing for their votes,” said Aranya.

Integrated Planning

At the same time, integrated urban planning is essential to address the long-term problems that such strong urbanization causes, says Professor Dag Kittang, from the Department of Urban Design and Planning.

“It is important to mobilize local resources, but that doesn’t need to prevent us from integrated planning. It is absolutely essential that rapidly growing cities have a structure that will also work over the long term. And that requires more and better urban planning and stronger institutions,” he said.

Sustainable urban planning has to make accommodation for more densely settled cities, with sensible coordination of land use, sustainable transportation and infrastructure development. Functional designs and structures are also important in enabling these areas to contribute to economic growth,” says Kittang.

“We need more compact cities, preferably with many centres,” agrees Aranya.

Mixed construction, without clear distinctions between commercial and residential areas, can also help reduce the need for transport.

“In traditional Western planning, industry was separated from housing because it was polluting. Much of today’s modern industry is not like that,” Aranya adds.

Sensible, comprehensive planning and land use require strong institutions that have the power to deliver results – like in China.

“But the Chinese are still stuck in a traditional Western planning paradigm, with suburbs and car-based land use. This approach is already about to collapse in several places. We see almost no bicycles in Beijing anymore.

Instead, cars are stuck in endless queues, and move much more slowly than bikes used to do,” says Kittang.

Climate change and growth

Rapid urbanization will also have consequences for climate change. Major cities in developing countries often have higher emissions of greenhouse gases per person than in rural areas (while the opposite is often true in developed countries). In addition, greenhouse gas emissions are increased by the production of materials for new buildings and infrastructure. Meanwhile, rapid urban growth results in more people living in vulnerable areas that will be harder hit by climate change. Failed policies will reinforce both problems.

Daniel Mueller is a professor at the Department of Hydraulic and Environmental Engineering at NTNU. He is one of 16 scientists who are working on a chapter on population, infrastructure and land use planning for the next assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which will be presented in 2014.

The 16 authors will review and summarize all available research literature on the topic.

“Urbanization has not been covered in this way in previous IPCC reports. Now there’s a chapter on urbanization in both the sub-report on emissions reductions and in the chapter on adaptation,” he says.

His starting point is the study of material and energy transfers in the community, or society’s metabolism, as he calls it.

“It’s a bit misleading to talk about cities as sustainable systems on their own. They rely on outside resources for their metabolism. They are thus partly responsible for the emissions from the production of goods and services they consume, even if emissions are produced in a completely different place. If cities are going to be made more sustainable, it is not enough for them to reduce their own emissions, the main thing is that they have to contribute to reductions in the total emission levels,” says Mueller.

Steel and cement

“We must analyse material flows to understand the relationships between different sectors. If not, we risk creating the problem that emission cuts in one area lead to increased emissions elsewhere,” says Mueller.

Mueller uses steel and cement, the main raw materials for buildings and infrastructure, as an example. Production of these two substances alone account for more than 40 per cent of emissions from all industries, and is as large as all urban transport.

“If, for example, we replace existing buildings with more energy-efficient structures, we will need more steel and cement. Emissions from their production must also be taken into account,” he adds.

In addition, the recovery of several important metals and minerals has become more expensive and more energy-consuming over time, because the percentage of metal in the ore is generally lower than in the past. Thus, more energy is needed to produce a given amount of iron, for example, which in turn results in increased CO2 emissions.

“Developed countries have the ability to recycle materials that are already in use.

In the US there is more iron in use than is available from known iron reserves. Much of the iron is found in buildings and infrastructure that should be replaced. Geologists can actually ‘prospect’ for metals in these buildings. Tomorrow’s mines will be found above ground,” says Mueller.

Cities in industrial countries thus have large amounts of CO2 embedded in infra structure that has been built over the last hundred years – a kind of CO2 bonus built into their buildings. Recycling scrap metal requires less energy than mining and refining metal from ores, which means that CO2 emissions from recycling are lower.

Incompatible with 2-degree goal

Developing countries are in a much more difficult situation than their developed counterparts. They have to build their infrastructure from scratch, and are dependent on primary sources of materials. These materials are becoming ever more expensive, require more energy to produce and result in higher CO2 emissions than in the past.

“We have attempted to calculate how developing countries can build the urban infrastructure they need with minimal emissions of greenhouse gases. We found that just the urbanization we now see is incompatible with the goal of limiting global warming to two degrees,” says Mueller.

But developing countries can at least try to learn from our mistakes and do things smarter, he said.

“We need urban systems that give residents viable offerings, with less material use and emissions. We have attempted to calculate an optimal density for cities. Los Angeles is located at one end of the scale. It is the epitome of sprawl, and has gobbled up a lot of infrastructure. But settlements may also be too dense. If you want to make settlements really dense, you have to build up, and that requires more steel. We’re trying to figure out what’s the ideal,” Mueller said.

Pricey adaptation

But we also have to assume that the temperature will rise, which intensifies the need for adaptation, especially in developing countries. The way the world is now is very unjust, because the people who have contributed the least to cause climate change are also the ones who will be most affected by it.

“Adaptation to climate change will take a lot of resources,” says Mueller.

At the same time, strategies for adaptation and emission reductions have to be coordinated, so that adaptation in one area doesn’t cause emission increases elsewhere, he says.

The world’s largest aid organizations believe that climate change and rapid urbanization will play an ever-greater role in shaping humanitarian crises in the coming years, according to a survey conducted by the Alertnet news service in 2012. Most organizations have emphasized the need to focus more on preventive measures to create more robust and resilient settlements. One dollar of prevention can save four US dollars in emergency aid, the International Red Cross Federation has estimated.

The problem is financing these measures. It is less sexy for donors to fund drainage systems than the handing out of food rations to flood victims, as one aid organization has said.

Climate refugees

More than 40 million people in Asia were displaced by extreme weather in 2010 and 2011, the Asian Development Bank ADB wrote in a March 2012 report. The report looks at the relationship between climate change and migration.

Climate refugees flee to megacities. And most of Asia’s megacities are already highly vulnerable to climate change, says the ADB report. Among them are cities like Guangzhou, Seoul, Dhaka, Kolkata, Mumbai, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Manila and Jakarta. Jakarta has an additional problem: The city is sinking ten times faster than the Java Sea is rising. The causes are many, from increased use of groundwater to a growing population, as well as larger buildings. Most of the new skyscrapers are actually pushing the ground down.

Urban flooding is a serious and growing problem for rapidly growing cities in devel- oping countries, according to ADB, which in February 2012 presented a special guidebook for flood prevention. It includes physical measures, such as drainage and green spaces; land use planning; and systems that can provide early warnings of flood damage.

“Urban expansion often creates poor neighbourhoods that lack necessary infrastructure, and thus become more vulnerable to flooding,” said the bank’s vice president, Pamela Cox, when the guidebook was presented.

“But rapid urbanization also means that we have the ability to do things right from the start, and achieve sustainable urban development that saves lives and money,” she added.

Vulnerable settlements

Let’s return to Kampala. Uganda’s capital lies on the shores of Lake Victoria, which means that sea level rise is not a problem. Nevertheless, the city has been subject to an increase in flood damage in recent years, mainly because residents in informal settlements are very vulnerable, says Musa Timbitwire.

Timbitwire teaches architecture and planning at Makere University in Kampala, and is now a candidate in NTNU’s master’s programme in urban ecology. He knew what his thesis topic would be even before he started: Vulnerability and adaptation to climate change in Kampala.

“Kampala is built on seven hills. The land is privately owned – and expensive. People who migrate to the city, end up in the low-lying, flood-prone areas between hills. It’s not a good place to stay, but they have no other choice,” said Timbitwire.

The large influx of people is causing the existing infrastructure to collapse. Drainage ditches are built over or filled with junk and blocked. Roads wash away.

Also vulnerability increases. In February 2012, eight people were killed after two days of heavy rain. The combination of more people in vulnerable areas and heavier rainfall is fatal.

“Everywhere is vulnerable: homes, livelihoods, infrastructure, health. The government sees these areas as little value and would rather not spend money to fix what is broken,” says Timbitwire.

But people continue to flock to the city and settle in vulnerable areas because they have no other choice. People who work in the informal market in the city, have to live within walking distance of the market, or they have to use half of what they make on transport. Therefore, they crowd together in the central settlements, perhaps by building a shed across a drainage ditch.

Rich countries have pledged to provide assistance to adapt to climate change. But efforts to create more robust, resilient communities must start at the grassroots level, Timbitwire thinks.

“We need action – at local, national and international levels. But we must take into account the community’s own resources and ideas. Some of these measures may be entirely local. For example, getting people to compost fruit peels and vegetable scraps instead of throwing them in drainage ditches. Actions on the national level must also be included. A national deposit system for plastic bottles will help to reduce the problem of drainage ditches that are blocked by trash,” says Timbitwire.

Because the condition of a drainage ditch can mean life or death the next time it pours down with rain in Kampala.

“Do no harm!”

But back to the question we started with: Can growth be planned?

Le Corbusier is dead. So is the vision of thoroughly planned cities, with big cities operating like well-oiled machines. Megacities live their own lives, they cannot be controlled by plans created at someone’s desk, and dropped down on the heads of people.

Planners cannot subvert urban development. But they might be able to influence its direction and pace.

“Sustainable planning is all about enabling people to create a better life, based on their own resources, in a way that does not destroy opportunities for others, born or unborn,” says Professor Bjønness.

“We can help planners with knowledge and understanding about the city’s diversity and dynamism. We have to do that with the people for whom the planning is being done. We have to start somewhere. Every problem can’t be solved at immediately. The goal is to create development together with those who need it most,” says Bjønness.

“We must never forget whom we are planning for,” says one of the slides he uses in a lecture on urban ecology. He also has another strong message, repeated on several slides. It is one of emergency medicine’s basic rules and says: “DO NO HARM!”