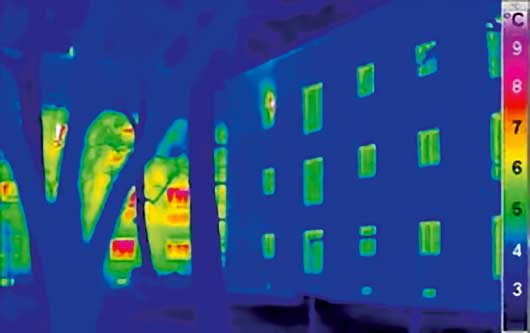

Passive houses save lots of energy

Housing is the easiest sector to change if we are to reach the climate targets.

By 2050, 7 million people will live in Norway instead of the 5 million that live here today. In spite of this growth, Norwegian energy consumption for housing could be 75 per cent lower than it is today, which would drop carbon emissions from the sector by as much as 70 percent.

So says Stefan Pauliuk, a postdoc in the Industrial Ecology Programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

Pauliuk estimated how Norway could reduce its emissions and energy consumption using several different scenarios as a part of his doctoral dissertation.

One-third of the power

The housing sector today represents about one-third of the country’s energy consumption, or about 35 terawatt hours out of a total of 112 terawatt hours. As a result, it is indirectly one of largest contributors to Norway’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“The so-called ‘green power’ we produce could be better used for other things than heating houses. We could use it for electric cars or the metal and oil industry and replace a lot of the fossil fuels we use today. If the UN and we are to reach our climate targets, and show the world that we are serious about this, this is a good place to start,” says Pauliuk.

New models

Pauliuk calculated different scenarios for the industrial sector, the transport sector and the housing sector to estimate conditions in 2050. With fellow student Karin Sjöstrand and supervisor Professor Daniel Beat Müller, he estimated how much we could save in energy consumption if the Norwegian housing stock was built according to, or upgraded to, a passive standard. A passive house is one that is designed and built to use very little energy for space heating or cooling.

Pauliuk and his colleagues also included variables in their model such as population growth, technical disadvantages, energy needs, different heating systems, different ways of living and greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental influences during, building, demolition and rehabilitation.

“No one has previously published models that include all these variables,” Pauliuk says.

What if this or that

A passive house is designed to not consume much more energy than what the sun, electrical appliances and humans themselves contribute. A house like this works because of passive measures such as insulation, high density, good windows, utilizing solar energy and heat recovery in the ventilation – and hence the name.

Pauliuk has estimated how much energy housing in Norway will consume during the next 40 years if Norway does nothing, if we build and renovate houses as is currently done, if the entire housing stock is torn down and reconstructed, if everything is build according to passive standards or renovated to these standards, if the living space per person is reduced, or if everyone uses efficient electrical appliances and water heating.

A combination of the three last measurements gives the best effect, also when you consider what happens during construction and demolition and the estimated increase in the population of about 50 percent. In this case, the yearly energy consumption of Norway’s housing sector will then be reduced from 34 TWh to around 10 TWH by 2050.

Pays off over time

Very few houses in Norway today are built according to passive standards.

“Tearing down all of our houses is probably not an option. It is not the most energy efficient solution anyway because of the emissions from demolition and building anew,” says Pauliuk. “But completely renovating the housing stock is possible. There will of course be cons to this approach. It will require 40 years of commitment and large investments. But considering future prices on carbon emissions and an increased pressure on the energy market it is likely that these measures will be cost efficient.”

The easiest sector

The UN’s climate targets mean that global greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced by 80 per cent by 2050. Norway’s goal is to be climate neutral by 2030.

“Norway is one of the richest countries in the world and housing is the easiest sector to change if we are going to reach the climate targets. It is technically possible and economically profitable. If we can’t do this we have no right to accuse other nations of not contributing,” Pauliuk says.