Ebola’s deadly toll on healthcare workers

Ebola’s deadly effects on the Sierra Leonean healthcare community not only has repercussions for the delivery of health care now, but on the training of future health care providers involved in an innovative Norwegian surgical training programme.

Since its first outbreak in Guinea in December, 2013, Ebola has hit West African healthcare providers disproportionately hard. At least 240 workers have been infected, more than half of whom have died, according to the World Health Organization.

Those grim statistics hit home for CapaCare, an innovative Norwegian-created surgical training programme in late August with the death of one of the programme’s two-dozen students, Joseph Heindilo Ngegba.

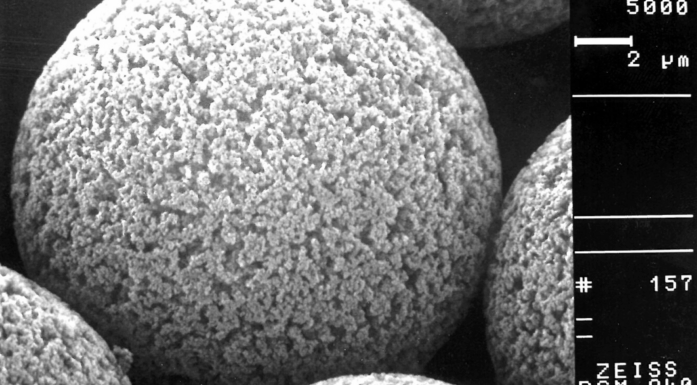

One of the biggest challenges facing health care workers in Sierra Leone is providing emergency surgical care to pregnant women. CapaCare provides this training. Photo: CapaCare.org

“Health care workers are Ebola’s collateral damage,” said Håkon Bolkan, a Norwegian surgeon and head of CapaCare, the non-profit organization he helped establish in 2011 to train community health officers in Sierra Leone to perform life-saving surgeries. “There are fewer health care workers, and the health care system is collapsing.”

- Read more: When the doctor is out

Shortly before he contracted Ebola, Ngegba himself wrote on CapaCare’s blog of the stress of working with the disease as a constant threat.

“The Ebola epidemic is having a negative impact on my daily life, with regards to my work in the wards, and the surgeries we perform, because you don’t know if the people you are working with have been exposed or not,” he wrote. “It’s really stressful…The attitude of people towards the Ebola outbreak is negative, because most people don’t believe there is Ebola. They think health workers are killing their people.”

A system under stress

Sierra Leone already has among the worst doctor-to-patient ratios in the world, with less than 150 doctors for its 6 million residents. That’s one doctor for every 45,000 people, according to the WHO, compared to one doctor per 410 people in the US and roughly one doctor per 270 people in Norway. In 2008, the country had 10 surgeons to serve the entire country.

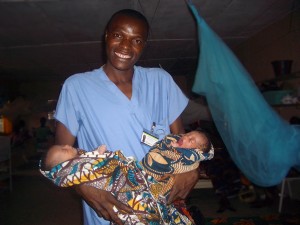

Samuel Batty, left, and Mohamed Kamara are community medical officers in Sierra Leone and students in the CapaCare surgical training programme, which is headed by NTNU surgeon and PhD student Håkon Bolkan. They came to Norway in September 2014 for additional training. Photo: CapaCare.org

Samuel Batty and Mohamed Kamara are community health officers in Sierra Leone and CapaCare trainees who came to Norway in early September for additional training.

Both men said they were under pressure from their families to stop working in the health care system for fear that they, too, might be infected. But they made it clear that they were committed to continuing their work.

“Health care workers have to help in the fight,” Batty said. “We have to be cautious not to contract the disease, but we are at war with this disease and we want to do our part.

Fear keeping patients away

Bolkan is also a PhD candidate at NTNU’s Faculty of Medicine, and is looking at the effectiveness of CapaCare’s training in expanding medical services provided to Sierra Leone, especially in more remote areas for his dissertation. He said that fear of Ebola was also driving patients away from Sierra Leone’s health care system overall.

“The mortality in pregnant women and other patients who are not coming in to seek care is most likely far greater than the mortality caused by Ebola,” he said.

As a result, the number of patients that the CapaCare trainees were able to help had dropped precipitously.

CapaCare

- A surgical training programme that trains community health officers in Sierra Leone how to do lifesaving emergency surgeries, such as Caesarean sections.

- Started in 2011, based on a previous charitable group called Friends of Masanga Norway.

- Headed by NTNU PhD and surgeon Håkon Bolkan and headquartered out of St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim.

- Nine of the largest hospitals operated by international non-governmental organizations in Sierra Leone with experienced surgeons and obstetricians are partners in the training program.

- All candidates are initially trained 6 – 9 months at Masanga Hospital, and are later posted to other surgical and obstetrical hospitals on 6 months rotations, before the final exams after two years of training.

- The training is followed by one year surgical and obstetrical housemanship. The program is conducted in partnership with the Ministry of Health and Sanitation.

- website: https://capacare.org

In another CapaCare blog post, trainee Hassan P. Vandy explained how this drop in numbers was playing out in his hospital.

“The hospital used to be a busy one since my arrival from Masanga Hospital. The daily outpatient flow has been ranging between 70 – 100 per day and 8-10 surgeries per week including emergencies,” Vandy wrote on 27 August. “Since two weeks back, the flow has dropped from the above figure to 10-15 outpatients per day and only 3 surgeries in two weeks.”

Hard not to help

Bolkan said that all these factors had led to CapaCare stopping its clinical rotations for their trainees for the moment.

“Given the crisis, we have to find new solutions, more online training,” he said.

Sierra Leone has one of the lowest doctor-patient ratios in the world, according to the WHO. Photo: CapaCare.org

Kamara, who came to the CapaCare programme after he had essentially taught himself to do Cesarean sections and other life saving surgery, said he felt frustrated that he couldn’t do more to help.

“It is very difficult when you see the suffering, you want to help,” he said.

On Thursday, 4 September, WHO director general Margaret Chan called the Ebola outbreak “the largest, most complex and most severe we’ve ever seen,” and said it would take 6-9 months to control at a cost of USD 600 million.

See a video of one of the first CapaCare trainees, Emmanuel Tommy: