Dissolving cholesterol crystals may help treat heart disease

An American mother’s hunch might result in new treatments for patients who can’t tolerate conventional cholesterol-lowering drugs.

An American mother with twin daughters with a rare incurable disease may seem like an unlikely partner in cholesterol research. But when Chris Hempel read about the role of cholesterol crystals in heart disease in 2010, she immediately thought of her daughters Addison and Cassidy, whose cells are unable to get rid of cholesterol.

Perhaps the experimental drug that was being used to treat her girls could also treat people with heart disease? She contacted Eicke Latz, the University of Bonn researcher behind the study, and suggested he look into the idea. Latz is also an assistant professor at NTNU’s Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR).

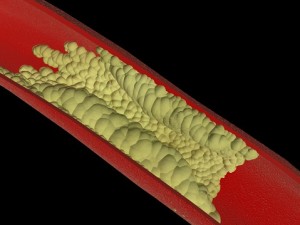

Too much cholesterol can create plaque along the insides of arteries and can result in hardening of the arteries. In the worst case, arteries can be completely closed off by plaque buildup, or they may become so narrow that a blood clot can form, causing a heart attack or a stroke. Photo: Thinkstock

Six years later, Hempel’s hunch has been confirmed: in a paper published in early April in Science Translational Medicine, Latz and an international team reported that the drug cyclodextrin can dissolve cholesterol crystals so they can be excreted by the body. The drug also changes the way the body’s immune system responds to the presence of cholesterol crystals, reducing inflammation in artery walls. Hempel is listed as one of the co-authors.

Although there already are different medicines on the market that can treat high cholesterol, some people experience side effects from these drugs. Cyclodextrin thus offers a potential new therapy for cardiovascular disease, Latz and his colleagues say.

Disappearing plaque

Your body needs (and makes) cholesterol in small amounts, but too much cholesterol can lead to hardening of the arteries, or atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is when artery walls are coated in plaque, which is made of a mix of cholesterol, calcium and other substances. The plaque makes arteries less flexible and causes them to narrow, thereby reducing blood flow. Eventually the arteries may be completely closed off by a blood clot, which can cause a stroke or heart attack.

In the 2010 study that caught Hempel’s attention, researchers reported how cholesterol crystals were found to cause inflammation in arteries, which then led to atherosclerosis. When Latz and his collaborators, including Terje Espevik, head of CEMIR, heard Hempel’s idea to test cyclodextrin, they “jumped on it,” Espevik said.

- You might also like: Good cholesterol is getting even better

Tested in mice and in human plaques

The researchers tested cyclodextrin in mice that were fed a cholesterol-rich diet and that were prone to develop atherosclerosis.

“We saw that cyclodextrin prevented plaque formation. It even reduced the existing plaque the mice had in their arteries,” Espevik said.

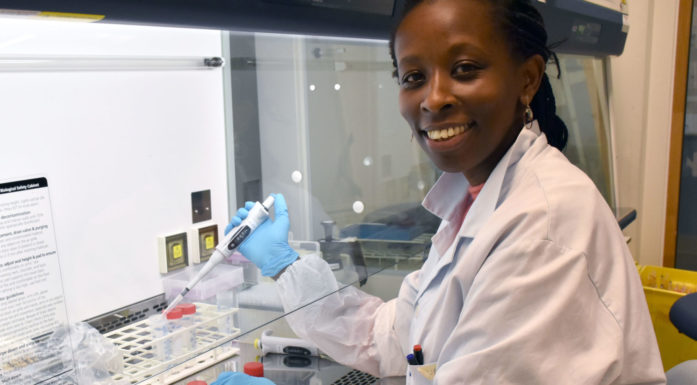

To see if the drug would also work in human tissue, CEMIR postdoc Siril Bakke was given access to a biobank, collected by Bente Halvorsen from the University of Oslo, OUS Rikshospitalet, with plaque biopsies taken from human carotid arteries. When Bakke examined biopsies of plaques treated with cyclodextrin, she found that the cholesterol was removed from the plaques. The cells in the plaque were also reprogrammed so they were in a reduced inflammatory state.

- You might also like: Mirror, mirror, will I have a heart attack?

Soaked up cholesterol and removed it

Another positive effect of cyclodextrin was that it reprogrammed macrophages, immune cells in the body that remove foreign or bad substances, Espevik said.

“What cyclodextrin did was to reprogram the macrophage so it didn’t create such a big inflammatory response,” Espevik said. That meant the macrophage could soak up excess cholesterol and remove it, while reducing the inflammation in the artery walls and thus reducing the likelihood of causing a plaque to form.

That means that cyclodextrin works via two mechanisms, Espevik said. The first is to dissolve cholesterol crystals so the body can excrete them, and the second is to reduce the inflammatory response in artery walls when macrophages soak up cholesterol crystals.

Promising therapeutic approach

The findings were so positive that the research team is now hoping to find funding and an industrial partner to conduct clinical trials in humans, Espevik said.

Latz estimates it will take approximately EUR 1 million to do the trials. One potential drawback is also one of the most positive aspects of cyclodextrin: the substance, which is a type of sugar, has already been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in humans. But because it has been in existence for some time, it cannot be patented. That makes it harder to get a drug company interested in developing cyclodextrin to treat heart disease, but it also will make it easier to get the drug approved to treat heart disease if the clinic trials support the research findings.

In addition to Latz and Espevik and their colleagues at the University of Bonn and NTNU, scientists from the University of Oslo/OUS Rikshospitalet and from Australia, the USA, Denmark and Sweden contributed to the research.

Reference:

Cyclodextrin promotes atherosclerosis regression via macrophage reprogramming. Sebastian Zimmer, Alena Grebe, Siril S. Bakke, Niklas Bode, Bente Halvorsen, Thomas Ulas, Mona Skjelland, Dominic De Nardo, Larisa I. Labzin, Anja Kerksiek, Chris Hempel, Michael T. Heneka, Victoria Hawxhurst, Michael L. Fitzgerald, Jonel Trebicka, Ingemar Björkhem, Jan-Åke Gustafsson, Marit Westerterp, Alan R. Tall, Samuel D. Wright, Terje Espevik, Joachim L. Schultze, Georg Nickenig, Dieter Lütjohann and Eicke Latz. Science Translational Medicine 06 Apr 2016:

Vol. 8, Issue 333, pp. 333ra50

DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6100