Finding ways to fix the climate before it’s too late

Scientists and policymakers rely on complex computer simulations called Integrated Assessment Models to figure out how to address climate change. But these models need tinkering to make them more accurate.

We know that greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels and other economic activities are warming the Earth and changing the climate.

The North Pole provides just the latest disturbing evidence of this fact. Right before New Year’s, the International Arctic Buoy Programme recorded temperatures there that were right around freezing, or more than 30 degrees C. warmer than usual.

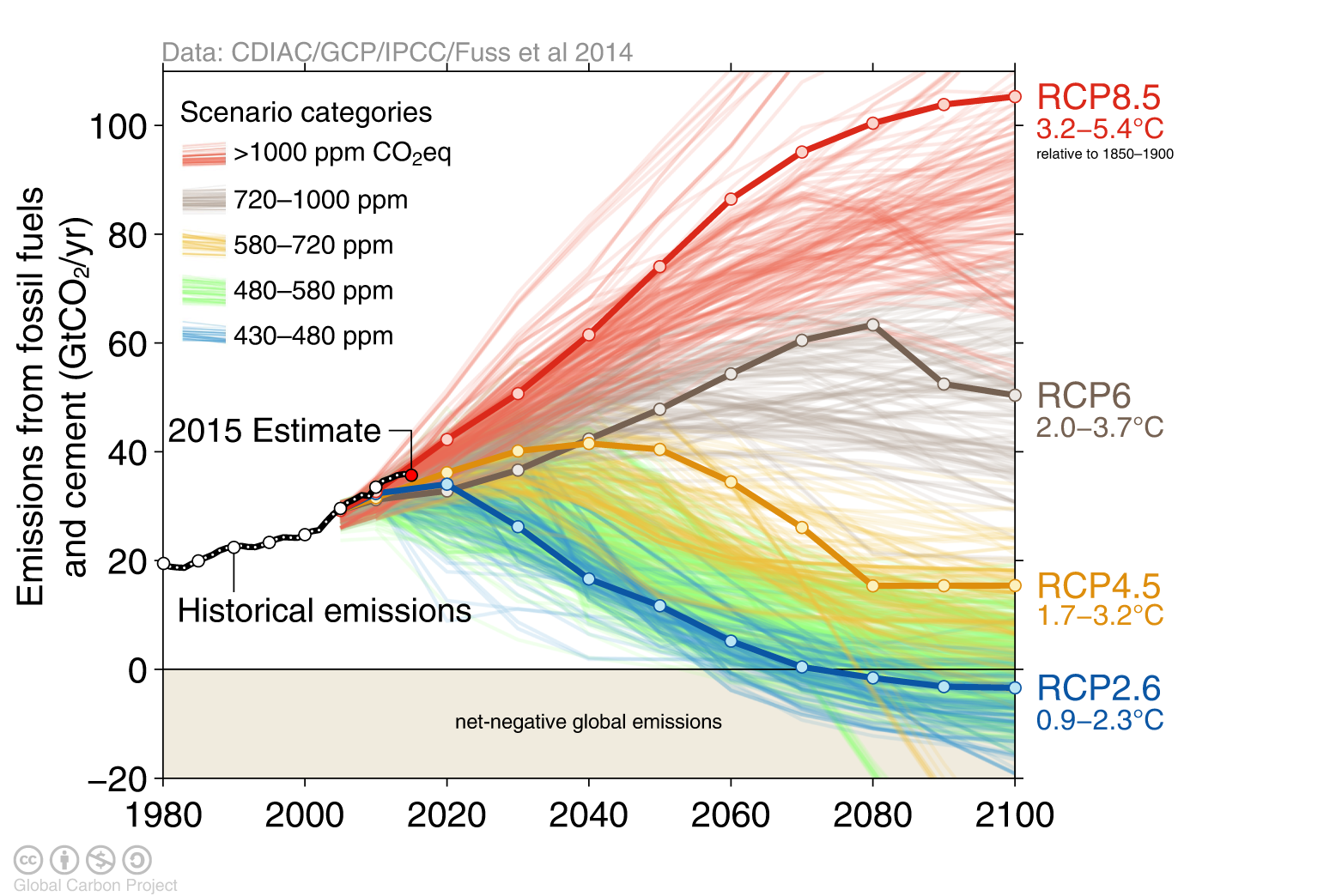

This graphic shows approximately 1200 different future scenarios of what the climate will look like, with each scenario a different mix of technologies and government policies. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, relies information like this to see how different combinations of technologies and government regulations will affect global climate until 2100. Graphic: Global Carbon Project

Deciding which large-scale economic and social changes to make so we don’t overheat the planet is not easy, however. Researchers around the globe have built complex computer simulations, called Integrated Assessment Models, or IAMs, that give them a view into possible futures. The models predict what would happen to the climate over the next 80 years based on different mixes of government policies and technologies.

“These models are really important in shaping policy and our current understanding” of how different strategies will affect the climate, said Anders Arvesen, a researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in the Industrial Ecology Programme.

But Arvesen and colleagues say there are ways to make the models even better, an approach they describe in an article in Nature Climate Change, published online on 4 January.

“Since we only have one Earth to experiment with, we need some kind of test field to study and test the impact of different strategies before we implement them,” said Stefan Pauliuk, a researcher at the University of Freiburg and the study’s first author. “IAMs are the most important test field we have…but how robust are these scenarios, how much can we trust that the technological mix calculated will actually lead to the outcome envisioned by the model?”

The opening ceremony of the Fortieth Session of the IPCC, in Copenhagen, Denmark, 27 October 2014. Approximately 450 participants attended IPCC-40, including government representatives, authors, representatives of UN organizations, members of civil society, and academics. Photo: IPCC

Scenarios can help decide policies

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, commonly called the IPCC, was established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988. Its mandate is to provide the world with a clear scientific view on the current state of knowledge on climate change and its potential environmental and socio-economic impacts.

Over the decades, the panel has published a series of reports and assessments for policymakers and the public. The most recent report, the 5th Assessment, was finalized in November 2014 and included many different scenarios based on IAMs.

The fact that the IAMs are so influential is why Pauliuk, Arvesen and his colleagues decided to give them a hard look, Arvesen said. “They (IAMs) have been successful and provide useful insights, which is exactly why it is important to improve them.”

The Nature Climate Change perspective describes how the models could be improved using approaches drawn from industrial ecology, where researchers study the flows of materials and energy through society to understand the costs and impacts of societal choices.

Steel, other metals, cement and chemicals

One area where the researchers say industrial ecology might help improve the IAMs is with materials. For example, the production of steel, other metals, cement and chemicals (including plastic) account for roughly 50 per cent of all industrial greenhouse gas emissions.

Recycling of aluminium and other metals can make a difference in greenhouse gas emissions, but today’s climate model scenarios don’t always take this into account when they make their predictions. Photo: Thinkstock

But recycling of scrap metals, once done to reduce costs, also reduces greenhouse gas emissions, which should be factored into the IAMs, says Konstantin Stadler, one of the paper’s co-authors and a researcher at NTNU’s Industrial Ecology programme.

“This is one of the paths that is not considered in the IAMs yet, but maybe we need this to have a full understanding of how we can reduce CO2 emissions,” Stadler said. “What policy options do we have, and what kind of consequences would it have if we implement them?”

If the IAMs could be fine-tuned to include this perspective, you could improve the scenarios that the models predict, the researchers said. Alternatively, you might miss out on some significant actions that could make it easier to meet emissions targets, Arvesen said.

“If you do not account for the full spectrum of mitigation options or possible constraints in that part of the system, then you miss out on something that is potentially important,” he said.

No answers — yet

It will be difficult to limit global warming to under 2 degrees C, experts agree. But higher global temperatures will lead to increased droughts, more severe storms and higher sea levels. Photo: Thinkstock

The researchers don’t actually know yet how including more detailed representations of the industrial ecology into IAMs will affect scenario outcomes — but they hope their article will encourage researchers to consider the idea. It is already clear that doing so will enable IAMs to consider a wider spectrum of climate change mitigation options, including recycling and material efficiency, than is the case today.

“What we propose is basically a new line of research where we suggest the two groups work together,” Stadler said. “We identified a problem that needs fixing and suggest how it might be done.”

Reference: Industrial ecology in integrated assessment models. Stefan Pauliuk, Anders Arvesen, Konstantin Stadler and Edgar G. Hertwich. Nature Climate Change. Published online 4 Jan. 2017. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3148