Moonwalkers three

Just 12 Americans have set foot on the lunar surface, and of those, only six are still alive. Three—Buzz Aldrin, Charlie Duke and Harrison “Jack” Schmitt — will be in Trondheim at the Starmus Science Festival to talk about the future of humankind in space.

When a New York Times reporter asked former astronaut John Glenn what it felt like right before a launch, Glenn had a quick, but admittedly non-serious answer.

“How do you think you’d feel if you knew you were on top of two million parts built by the lowest bidder on a government contract?” he quipped.

Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, was at the forefront of the iconic space race initiated by US President John F. Kennedy in May 1961. His non-serious answer hints at the complexity of the effort that enabled astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin to step into history in July 1969 as the first men ever to walk on the Moon.

It’s easy now, in retrospect, to believe that there was something inevitable about reaching Kennedy’s goal. But even a brief look at the history of manned spaceflight shows just how incredible an achievement it was.

Everything had to be engineered from scratch, from the serious business of choosing a landing site and developing the rockets and spacecraft that would enable this feat, to the mundane details of how the American flag could be deployed in an airless wasteland. The schedule was so rushed that less than six months before Apollo 11, the lunar module had yet to be tested in its manned configuration.

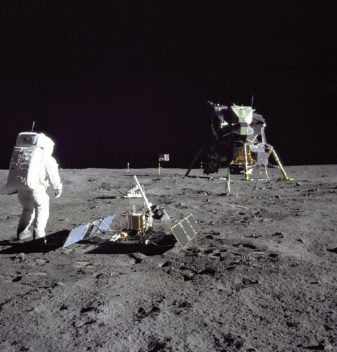

The Apollo astronauts left many bootprints on the Moon. Now they hope the nations of the world will send others to follow in their footsteps. Photo: NASA

The effort was anything but smooth. Early on, NASA sent a series of rockets to take pictures of the Moon’s surface and transmit the images back so they could find potential landing sites. Several of these reconnaissance rockets failed outright. Two overshot the Moon completely, one by 20,000 nautical miles. In the end, five managed to send back enough pictures so several landing sites could be selected.

There was also a terrible disaster, when astronauts Edward White, Roger B. Chaffee and Virgil Grissom died in a fire during a test of the Apollo 1 command module on 27 January 1967.

In its coverage of the Moon landing, The New York Times called the event “the realization of centuries of dreams, the fulfilment of a decade of striving, a triumph of modern technology and personal courage, the most dramatic demonstration of what man can do if he applies his mind and resources with single-minded determination.”

Sending humans to the Moon, our nearest neighbour in space, seemed an impossible task when US President John Kennedy first proposed the idea in 1960. In 1969, Apollo 11 achieved this goal. The photo shows the Moon from Apollo 13. Photo: NASA

And yet, the landing was preceded by just four other manned Apollo flights, where astronauts practiced the different manoeuvres that would be needed to send a man to the Moon and bring him back.

Apollo missions would continue for only 3 more years after Armstrong and Aldrin’s achievement. Even then, success was not guaranteed: Apollo 13 had to be aborted after one of its oxygen tanks exploded, although the men were brought home safely.

All told, just 12 men have set foot on the lunar surface; of those, only six are still alive. Three—Buzz Aldrin, Charlie Duke and Harrison “Jack” Schmidt — will be in Trondheim this June to talk about the future of space flight and the possibility of putting a man on Mars.

But as these octogenarians talk about their visions of the future, it’s hard not to wonder: What kind of person willingly, eagerly sits atop “two million parts built by the lowest bidder on a government contract”? What kind of a man does that?

Buzz Aldrin

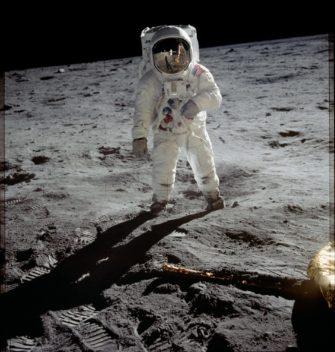

This interior view of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module shows Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., lunar module pilot, during the lunar landing mission. This picture was taken by Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, prior to the moon landing. Photo: NASA

Nineteen minutes after Neil Armstrong first set foot on the Moon, Air Force Col. Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin joined him, hopping off the ladder of the bug-shaped lunar module the last meter to the Moon’s powdery surface.

Decades later, when Aldrin was on a 2014 NASA panel to talk about his moon landing, he recalled “when it was my turn to back out, I remember the check list said to reach back and carefully close the hatch, being careful not to lock it.”

But perhaps his most famous statement is his description of the landscape around the lunar module, which he called “magnificent desolation.”

Aldrin seems almost to have been pre-ordained to become an astronaut. His father, Col Edwin Aldrin Sr., studied physics with Robert Goddard, recognized in the United States as the father of modern rocketry. Aldrin Sr. knew Orville Wright. And Buzz Aldrin’s mother’s maiden name was Marianne Moon.

Aldrin, born 20 January 1930, followed his father into a career with the military, and graduated third in his class at the United States Military Academy in West Point. He joined the budding US Air Force and was a fighter pilot during the Korean War, after which he took his PhD in astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His dissertation was on orbital rendezvous, and in October 1963, he was accepted in the third wave of astronauts recruited by NASA.

In a Life Magazine profile of the crew of Apollo 11 that ran just after the Moon landing, Aldrin was characterized as the “best scientific mind in space,” with one of his colleagues commenting how he had even carried a slide rule with him when he flew on Gemini 12. In fact, Aldrin had use for that slide rule. The radar on Gemini 12 failed, and Aldrin was able to manually calculate the manoeuvres the mission had been designed to test, a feat that helped win him the moniker “Dr. Rendezvous.”

The same Life profile also quoted an unnamed astronaut’s wife as saying that Aldrin was something of a “square.” “If Buzz had his way,” the unnamed wife told Life reporter Gene Farmer, “the code names for the spacecraft on Apollo 11 would be Alfa and Bravo.” Instead, the astronauts flew in the Columbia command module and the Eagle lunar module.

Aldrin proved to have a cool head. After their moonwalk, the astronauts discovered they’d managed to knock a piece off the circuit breaker that controlled the ascent engine — which was their ticket home. As he wrote in his autobiography, Magnificent Desolation, Aldrin realized a possible solution was riding in the shoulder pocket of his space suit.

“I had a felt-tipped pen in the shoulder pocket of my suit that might do the job. After moving the countdown procedure up by a couple of hours in case it didn’t work, I inserted the pen into the small opening where the circuit breaker switch should have been, and pushed it in; sure enough, the circuit breaker held. We were going to get off the moon, after all.”

Aldrin left NASA in 1971 and continued to work with the Air Force as an officer and later as a civilian manager. But he struggled with depression and alcoholism, which he candidly wrote about in “Magnificent Desolation”. In a 2009 interview with the New York Times, he said, “I inherited depression from my mother’s side of the family. Her father committed suicide. She committed suicide the year before I went to the Moon.”

Now 87, Aldrin has been outspoken about the need for the US to lead an international effort to establish a human colony on Mars. “Our Earth isn’t the only world for us anymore,” he wrote in an opinion piece in 2013. “It’s time to seek out new frontiers.”

Charles Duke

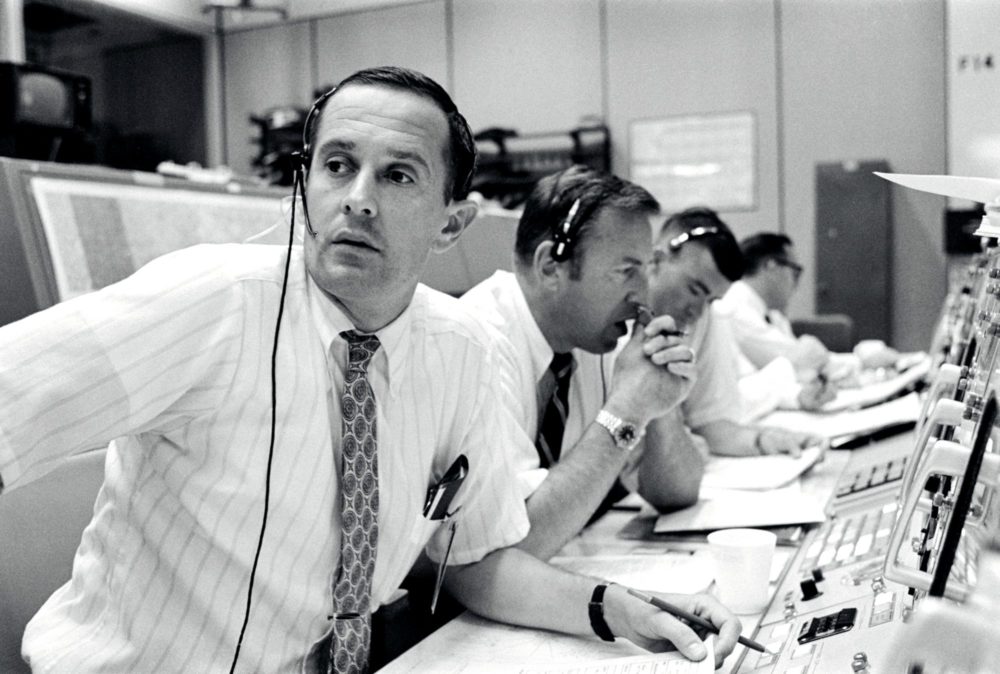

While most people can name the first two astronauts who walked on the Moon, the names of subsequent moonwalkers are less well known. Charles “Charlie” M. Duke Jr. was the tenth person to walk on the Moon in 1972, but he is almost certainly more well known for being the voice of Mission Control at Houston during the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Charlie Duke may be as famous for being the voice of Houston during Apollo 11 as he is for having walked on the Moon during Apollo 16. Photo: NASA

When Neil Armstrong announced the safe arrival of his spacecraft by saying “Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed,” it was Duke who replied: “ Roger Tranquillity, we copy you on the ground. You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Duke also unwittingly contributed to staffing changes for the ill-fated Apollo 13. He was the backup lunar module pilot for Apollo 13, and caught German measles from a friend’s child, which ended up exposing the main crew to the disease.

As a result, NASA doctors pulled Ken Mattingly from the main crew because he was the only one who was not immune to the disease, and sent Jack Swigert in his place. In the end, Mattingly and Duke worked together in the spacecraft simulator at Mission Control to develop a step-by-step procedure to safely bring the crippled spacecraft back to Earth.

In an oral history recorded by NASA’s Doug Ward in 1999, Duke said he had wanted to be an astronaut as soon as the US began sending men into space in 1961. He was a fighter pilot in the Air Force, which sent him to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for an advanced degree. After that, he went to fly at the Air Force Test Pilot School.

“Two months later there was an ad in the paper that said, ‘NASA’s looking for more astronauts,’ you know, ‘Please apply,’” Duke remembered. So he did.

“I love exploration and I love adventure,” he said in a video filmed when he was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame. “I volunteered just for the thrill of it.”

By the time Duke finally got to fly to the Moon with Apollo 16, the Apollo programme was being phased out, and the technical aspects of space flight seemed as if they had been worked out. The technology had advanced to the point where, starting with Apollo 15 in July 1971, the astronauts took their own 210 kg “moon buggy” or Lunar Rover Vehicle, with them on the flight.

Nevertheless, NASA nearly had to abort Apollo 16 an hour before the astronauts were scheduled to land on the Moon because of problems with engine vibrations in the command module, piloted by none other than Ken Mattingly. At this point, the command module, code named Caspar, with Mattingly, and the lunar module, code named Orion, with Duke and mission commander John Young, were already separated and several kilometres apart.

“Our hearts sank. If your heart can sink to the bottom of your boots in zero gravity ours did, because it was—I mean, there we were, you know, 2 years of training, 240,000 miles away, an hour before the landing on a orbit you can look down at your landing site, 8 miles beneath you, and they’re about to tell you to come home,” he said in the oral history interview. “And that’s what we thought was going to happen because it was, according to Mission Rules, abort.”

Once again, however, Mission Control managed to figure out a workaround, and the mission went ahead as planned, although delayed by 6 hours.

Apollo 16 was the second of Apollo’s so-called “J” missions, which involved a three-day stay on the moon and three different excursions on the lunar surface. All told, Duke and Young spent 20 hours and 14 minutes on their moon walks, collecting 95.8 kg of moon rocks, compared to Armstrong and Aldrin’s 2 hours and 31 minutes, during which they collected 20 kg of material.

Duke eventually retired from both NASA and the military; by the time he left, he was a brigadier general in the Air Force. He also became a born-again Christian.

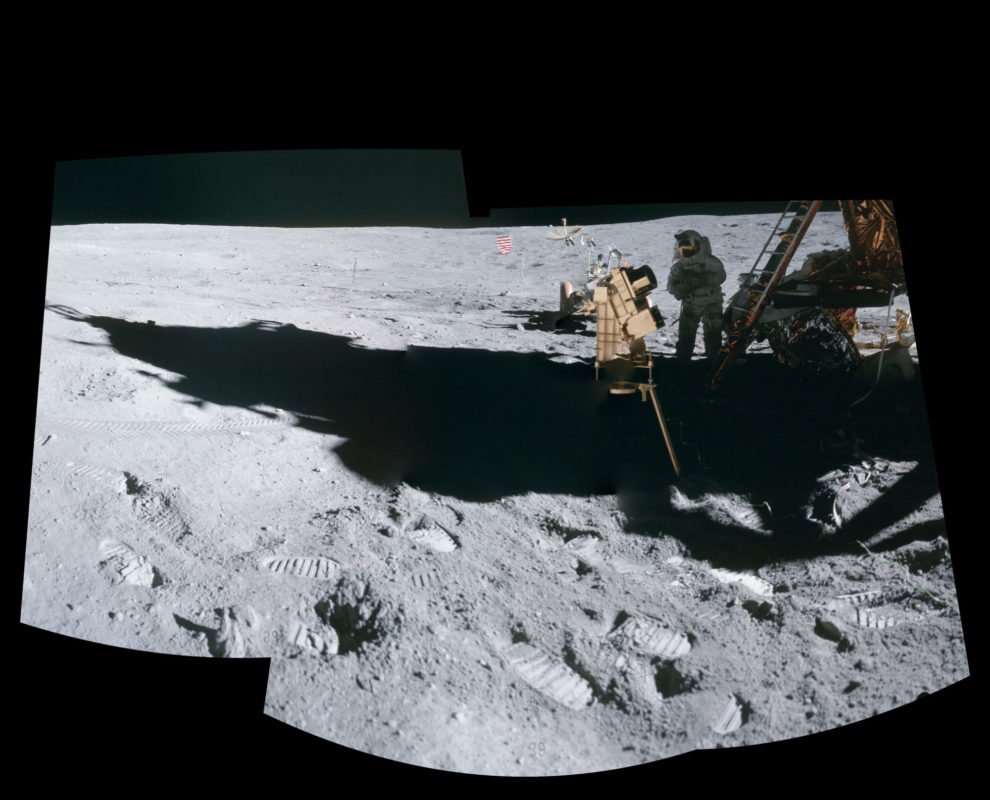

Apollo 16 included a Lunar Rover as part of its payload, which allowed astronauts to explore more of the Moon’s surface. Photo: NASA

He has continued to talk about the power of his experience, not only in visiting the Moon, but in seeing the Earth at a distance. During his lunar journey, 16,000 miles (26,000 km) away from the Earth, it suddenly floated into his window in the command module.

“You could see the whole circle of the Earth, it was the most awesome sight I had ever seen, it was breathtakingly beautiful,” he recalled in a 2009 talk. “A photo does not capture the emotion you have when you realize you are looking at the whole of the Earth, the circle of the Earth. ….It was just that jewel of Earth, suspended in the blackness of space.”’

Harrison “Jack” Schmitt

Scientist –astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt may be the only astronaut whose interest in space was fuelled when he was a student in Norway. In 1957, Schmitt was a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Oslo when the Russians successfully launched Sputnik. “It really did get my attention about how important space almost certainly was going to be in the future of humankind,” he said in a NASA oral history interview from July 1999.

So in 1964, after he had completed his doctorate in geology at Harvard University and was working at the US Geological Survey, he decided to volunteer for the first group of scientist-astronauts to be selected by NASA.

Harrison “Jack” Schmitt inside the Lunar Module after having been out on the surface of the Moon during Apollo 17. The use of Lunar Rovers during the last two Apollo missions expanded the ability of astronauts to explore — but the vehicles kicked up enormous amounts of dust, which explains why Schmitt’s once white spacesuit is grey with dust. Photo: NASA

“I can remember feeling at the time that if I didn’t volunteer, no matter what happened to my application, that I’d almost certainly regret it when human beings actually went to the Moon,” he said in the oral history interview.

The Moon as a goal was first and foremost a geopolitical play: Kennedy’s challenge to his nation was mainly motivated by the perceived Soviet superiority in space. But for scientists, the Moon offered an intriguing window on the history of the Earth, and on the formation of the Moon itself. Its airless, lifeless surface is a perfect place to preserve rocks — making it a perfect place to send a geologist.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t certain that Schmitt or any of the six other scientists that had been selected for the astronaut programme in 1965 would actually be tapped for one of the Apollo missions. But when NASA cancelled the Apollo programme, making Apollo 17 the last mission to the Moon, geologists rallied behind Schmitt and successfully pressured NASA to put him on the flight.

Astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt with the American flag during Apollo 17, the last mission to the Moon. The Earth is the tiny blue marble in the background, 400 000 km away. Photo: NASA

As part of his astronaut duties, Schmitt had a hand in teaching the Apollo crews how to take rock samples on the Moon and make observations. He also was able to study the samples that came back from the Moon. In fact, he worked so diligently with the Moon rocks he reportedly was able to name them by number as he zoomed past similar rocks on the lunar rover.

Not surprisingly, the last two men on the Moon set all kinds of records: they drove the farthest in their lunar rover — 30 km — collected a record 110.4 kg of rocks, and at more than 22 hours, spent the most time out on the Moon’s surface. Schmitt and mission commander Gene Cernan also took time to play in the Moon’s one-sixth gravity, kangaroo hopping and pretending to schuss down a steep slope. Schmitt later sang a silly song while cruising along the lunar surface, collecting rocks.

Decades later, as he reflected on the Apollo programme, Schmitt remarked that its impact went far beyond the considerable geological findings that he and the other astronauts were able to contribute to, with their observations and samples.

“Apollo had really two major benefits to humankind,” he told NASA interviewer Carol Butler in 1999. “One is, it demonstrated that free men and women, when faced with a challenge, can meet that challenge and succeed in a political and technological race that had a lot to with the preservation of freedom on this planet.”

The second benefit, Schmitt said, remained to be realized, in as much as the Moon has resources that could some day be used by humankind. “It is in the same class of those unanticipated returns that came from Lewis and Clark exploring the Louisiana Purchase, and really has always come from any type of human exploration that we’ve undertaken.”

Schmitt left NASA to run for the US Senate, where he served for one term. He has since worked as a consultant and held a variety of government appointments. He too, looks forward to the day when men — and women — will stand again on Earth’s nearest neighbour.