Making it harder to be a social media bully

Researchers have developed an approach that makes it easier to block abusive and hateful messages on the web.

The use of social media, online forums and blogs has exploded. Over four million Norwegians have a profile on social media. More and more people are exposed to hateful online comments, such as racist or sexist remarks or other bullying.

“Our main motivation is to make it easier to weed out harassment and bullying on the web. I’m thinking especially of vulnerable young people. Too many of them are subjected to online bullying and abuse,” says Ramampiaro. He is an associate professor in the Department of Computer Science at NTNU.

- You might also like: An app to help you stay safe

Works for all languages

Several solutions on the market eliminate unwanted text messages.

Ramampiaro and his colleagues at the Norwegian Open AI Lab have developed an approach that differs from existing solutions by analysing recurring user patterns in addition to text. This means that the software looks at individuals’ tendencies to use offensive language in previous postings.

The method is based on machine learning. It is trained to detect the offensive language tendencies and then it weeds out individual words and sentences. It can be used to filter out hateful messages before they are published.

The new method can be used to filter out hateful messages before they’re published,” says Ramampiaro. Photo: Kai Dragland, NTNU

Ramampiaro points out that his method is language independent and can be trained to handle any language.

- You might also like: Improving migraine treatment with an app

Tested on tweets

The researchers have tested the method on 16 000 Twitter messages and found that it successfully distinguishes racist and sexist comments from normal text.

“This method does a better job at identifying offensive utterances and singling them out from normal or neutral comments than existing state-of-the-art methods,” says Ramampiaro. He believes that this makes their approach more efficient than any other solution available today.

The researchers have focused on making it possible to integrate the method into a system that can classify text streams like Twitter messages.

Can save labour

Ramampiaro has seen that the method can be used to good effect, both in social media and in online news discussions.

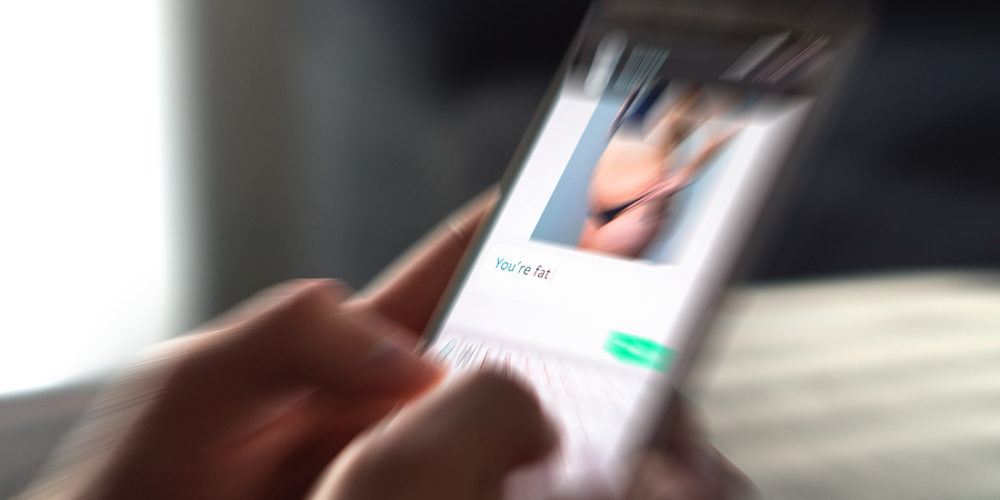

Too many young people are experiencing cyberbullying and harassment,” says Ramampiaro. Illustration photo: NTB scanpix

Today, Norwegian media houses rely on human beings to weed out hate speech after it shows up in their comments. What gets eliminated is subjective and, not least, very time consuming.

“For media houses that have had discussions ruined by hateful comments, the consequence is sometimes that the discussion has be closed down,” says Ramampiaro.

“If debates are silenced because of this kind of agitation, it can become a democratic problem,” he said.

- You might also like: Improve your Norwegian with a tailor-made app

Ethical dilemmas

It is efficient to use a technological method like this to track users who are inclined to spread racist and sexist statements, but at the same time it triggers ethical dilemmas.

One question is whether software can make correct judgements in terms of freedom of speech and censorship.

Ramampiaro thinks that a human being needs to be responsible for whatever is being filtered out. Even if a machine is able to do it, it’s not appropriate. “But when the system administrator has classified something as offensive, our method can remove it,” he says.

Tweets in dialect

Another challenge is that hateful comments or tweets often use abbreviations, slang or dialect.

Social media in Norway

According to Ipos, just under 3.5 million Norwegians over the age of 18 have a profile on Facebook, and 83% of them are on FB daily.

Over 1.8 million Norwegians have a profile on YouTube.

2.6 million Norwegians have a Snapchat profile.

2.2 million Norwegians use Instagram.

Almost 1.2 million Norwegians have a profile on Twitter

Statistics Norway states that 80 per cent of Norwegians between 16 and 79 years use social media. Among those between 16 and 24 years old, nine out of ten spend time on social media daily or almost daily.

“English tweets can be difficult on a purely linguistic level, because they use abbreviations and slang. But Norwegian is actually even more complex, because we have so many dialects. And it’s quite common to write tweets in dialect,” says Ramampiaro.

The researchers are continuing to collect an even larger foundation of data and plan to test the method in several languages.

They also want to expand the method to include speech, which will broaden the software’s scope. But this will happen sometime down the road.

“Right now we’re doing basic research that has an application aspect,” he says.

“Up to penal code to apply sanctions”

Toril Aalberg, head of NTNU’s Department of Sociology and Political Science, has spent time on political communication. She believes that the intent of the Open AI Lab method is good, but points out that several ethical issues need to be considered.

“Freedom of expression was introduced precisely to protect opinions we don’t like, while the penal code bears the responsibility for applying sanctions against people who publicly express discriminatory or hate speech. It can quickly become problematic if only users with communication patterns that are pre-approved as “normal and neutral expressions” reach the public,” says Aalberg.

She points out that it wasn’t that long ago that debate arose about Facebook’s pre-censoring of the unpleasant yet historically important picture of the naked «napalm girl» in Vietnam.

“The intention was good, but the result was completely wrong. Another equally important issue is that technological censorship solutions won’t remove the hatred itself, which may then well be expressed through other channels,” says Aalberg.

Can save lives

Ramampiaro says the researchers are aware that several ethical dilemmas exist. He thinks it’s challenging to look into a crystal ball and describe the consequences their software will have, but he knows one thing for sure:

“I hope the method allows us to more efficiently detect abusive language that harasses people. Being exposed to hate speech, racism and sexism can be very burdensome for individuals and in the worst cases can result in fatal consequences. There are examples of vulnerable youngsters who have ended up taking their own lives due to cyberbullying,” says Ramampiaro.

“So if we only save a single life, it’s worth it,” he says.

Reference: Pitsilis, G.K., Ramampiaro, H. & Langseth, H. Appl Intell (2018) 48: 4730. Effective hate-speech detection in Twitter data using recurrent neural networks