Eight myths about your brain

Do we have a dominant brain hemisphere? Do we use our whole brain? Can we train our brains to be smarter? Does our ability to learn depend only on our genetic inheritance?

The brain is popular like never before and it’s become cool to be smart. But how much do we really understand about how our own brain works? (At the end of the article you’ll find a quiz about the brain.)

NTNU researcher Fride Flobakk-Sitter in the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning has recently published the book Pedagogikk og hjernen (Pedagogy and the Brain), in which she looks at our common misconceptions about the brain. She is a postdoctoral student at NTNU and is researching the link between pedagogy, cognitive psychology and brain research.

Here she shares eight common myths about the human brain.

Myth #1: We only use a small part of our brain

The idea that we only use about 10 to 20 per cent of our brain is a classic brain myth, according to Flobakk-Sitter.

“It’s somewhat enticing to think that we have a large and ‘unused’ brain capacity that could potentially make us even smarter. But this is wrong. We use our whole brain,” says the researcher.

The brain is the organ in the body that requires the most energy. It is also limited in size due to the skull, so it makes sense to use its resources as efficiently as possible.

“The idea that we have 80 to 90 per cent unused brain capacity is completely absurd on the basis of what we know about the brain today,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

You may like to read more about this in Educational Research: Neuromythologies in education by John Geake

Myth #2: The brain develops only during the first years of life

It is commonly assumed that the brain changes a lot during the child’s first year of life, but that development stops at some point. Recent research debunks this notion. The brain is plastic and changeable throughout our lives.

“Our nerve connections and structures can change throughout our lives,” says Flobakk-Sitter and elaborates:

“As infants we have far more connections in the brain, because we’re born with a lot of synapses. During the first years of life, the number of these neural connections is drastically reduced.”

She explains that the brain has hedged its bets by having lots of connections from birth. Then the environment determines what’s needed and not needed. The connections that don’t get used become weaker.

As young children, for example, we can distinguish between phonological sounds in all languages, but if we don’t encounter them in our own environment, we gradually lose the ability to perceive them. That’s why older Japanese can’t distinguish between the sounds of r and l, whereas Japanese toddlers can hear the difference.

“A lot of people think that this is something negative and that we have to maintain these neural connections. But that’s a myth, says the researcher and compares the brain to a computer:

“If we have all the programs up on our computer, it’ll work more slowly. The brain would use a lot of energy unnecessarily if it maintained lots of unused networks.”

In other words, it’s good that the brain saves its forces by shutting down the pathways that aren’t in use.

You may like to read more about this in the Centre for Educational Research journal: Most learning happens in the first 3 years

Myth #3: If you lose a neural

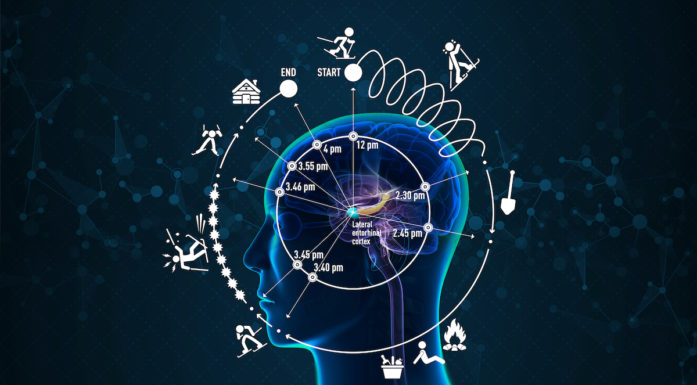

The brain changes according to the parts you use. Taxi drivers can train parts of the brain related to our sense of space and place. Illustration: Colourbox

pathway, you never get it back

It isn’t true that you can’t retrain a neural pathway that has been damaged. Deactivated neural connections can be restored and developed further.

“Only very few connections cannot be restored,” says Flobakk-Sitter. In other words, we have plenty of opportunities to learn something new even as we age.

- You may also like: Juggling enhances connections in the brain

Myth #4: You have the brain you’re born with

One common assumption is that our brain capacity and learning ability are shaped only by our inheritance and genetics. According to this myth, our genes determine how smart or stupid we are.

This is wrong too, according to the researcher.

“Inheritance and the environment both have a great influence on learning ability. We inherit some things from our parents that we’re predisposed to, but the environment also plays a major role.

Flobakk-Sitter refers to a study done among taxi drivers in London, which showed that the experience of navigating through the city streets led to structural changes in the part of the drivers’ brains that is linked to navigation and spatial memory.

You can read more about this study here: Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi or taxi drivers

“How we interact with the environment plays an important role in how our brain develops. Our genes contribute by forming the basis for how the nerve cells communicate with each other, for example. But genes don’t define who we are,” says the researcher.

Myth #5: Creative individuals have a dominant right hemisphere, and rational people have a dominant left hemisphere.

The idea behind this assumption is that our brains are either right dominant or left dominant and that this will define key characteristics of us as humans. The left brain is often associated with logic, reasoning, language, and more academic skills. The right brain is linked to creativity, emotions, imagination and artistic qualities.

“This is a classic and relatively tenacious brain myth,” the researcher says and elaborates:

“Although our brain can be anatomically divided into a left and right hemisphere, and although some functions are in one hemisphere, we can’t talk about right or left dominance in healthy people.”

We use different networks and several parts of the brain every time we perform a task.

“Some cognitive tasks can, of course, activate one half of the brain more than the other, but there’s no reason to assume that people are that different in terms of which side of the brain ‘d

ominates’ for different learning activities.

So the idea that left-handed people are more creative is wrong, too?

“Right, that’s part of the same myth. If you’re very creative and like to draw, you use both your right and left hemispheres. Big networks are working throughout the brain,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

- You may also like: Skill building the right way

Myth #6: We learn best by using our dominant senses

The notions of a dominant brain and dominant senses have gained a certain foothold among teachers, according to the researcher. This in turn has led to the idea of different learning styles.

“Healthy people generally don’t have dominant senses,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

The so-called VAK learning styles are based on the myth that some people learn by seeing (visually), some by listening (auditory) and some by touching (kinesthetic).

Some schools in the United States have gone as far as dividing students into groups according to their learning style. Sometimes the pupils even wear signs or t-shirts that show which group they are part of.

“Focusing that much on just one way of learning is doing children a great disservice,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

“It’s important to strengthen different brain circuits, and learning happens best when a child uses different ways of acquiring knowledge. The child needs opportunities to learn by listening, seeing and fiddling with things,” she says.

Myth #7: Children need enriched learning environments

Children who grow up under normal conditions will encounter the stimuli they need for normal learning and development. Photo: Colourbox

Another misconception is that children need special toys and activities designed to stimulate the brain.

Flobakk-Sitter says the idea that children need so-called enriched learning environments came from a rat experiment, where it was discovered that rats placed alone in empty cages had poorer cognitive development than rats placed in large cages with plenty of stimuli, such as exercise wheels, climbing poles and other rats.

“The study was incorrectly conveyed in a number of forums outside academia,” says Flobakk-Sitter. She points out that the rat study doesn’t say anything about how children respond to enriched learning environments, rather, it simply speaks to the rats’ reaction to a deprived – that is, poorer – learning environment.

“That has created a misunderstanding around what kind of stimuli are needed. The idea of enriched learning environments has led to a market for so-called ‘brain stimulating’ toys that purport to make your child smarter,” she says.

This is completely unnecessary, according to the researcher.

“Children are very teachable and skilful. But that doesn’t mean that parents need to be completely hysterical about giving the children the right ‘brain toys’ or start teaching them Japanese when they are small. The truth is that children who grow up under normal conditions will encounter the stimuli they need for normal learning and development,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

In the journal Nature you can read: Neuroscience and education: from research to practice? (article is behind pay wall)

Myth #8: You can train your brain to be smarter

The fact that it has become cool to be smart has created a market for books, programmes and apps to help us train our brains.

“Brain training has become a popular umbrella term for various cognitive tasks. You have brain training programs, books, various math tasks and brain training through physical movement. But training your brain to be smarter is only partially true – it’s a truth with qualifications,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

“It’s good to keep your brain active. But paying huge sums to solve brain tasks doesn’t generally give you higher intelligence. If you’re good at solving Rubik’s cube, you’re not necessarily good at solving math tasks or speaking French,” she says.

She encourages thinking about whether the exercises have a transfer value and long-term effect, and reminds us that brain training doesn’t necessarily make you smarter.

But can’t you train your brain?

“We actually do that every day. You use your brain every day, you do fine without buying these expensive programs. You might as well learn to knit or play football if you haven’t done them before. Learning something new and breaking the routine are good for the brain.

Academic doping

Some people go even further in the hopes of getting smarter – which is not always that smart. Smart pills and electro-doping are two questionable methods which, according to the researcher, are more widespread than we might think.

Medications intended for patients with ADHD, narcolepsy and Alzheimer’s, for example, fall into the category of smart pills, or academic doping. Many of these are classified as narcotics and should not be used by healthy people.

“We know way too little about the long-term effects of the various smart pills on a person’s learning performance. A ‘quick fix’ like a smart pill provides no guarantee for a deeper understanding and learning of academic topics. It can also be dangerous. And it’s also unethical,” says the researcher.

You can read more about this on Made for minds: The dangerous side effects of ‘smart drugs’

Current to the brain

Stimulating the scalp with small electrical impulses – known as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) – is based on the fact that brain cells use electricity to communicate.

“The idea is that if you send an electrical current through the brain, the brain cells will fire faster. This is scary. The side effects are unknown, and the likelihood of a positive long-term effect from this is very small. If you try this at home, you won’t be smarter half a year from now. But you may inflict burns, strokes or other long-term damage to the brain. Improper use of tDCS technology is downright dangerous,” says Flobakk-Sitter.

Want to know more?

- More information can be found in the journal News Medical Life Sciences: Experts warn about risks involved in home use of tDCS

- Fride Flobakk-Sitter’s PhD thesis from 2015: The Development and Impact of Educational Neuroscience

- Link to Fride Flobakk-Sitter’s book Pedagogikk og Hjernen (in Norwegian)

- Quiz about the brain