From programming a calculator to activist professor for gender equality

Letizia Jaccheri has won a Norwegian award recognizing her efforts to bring more women into the tech industry. She’s been instrumental in helping increase the number of women in leadership positions at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), where she herself is a professor of computer science.

If you ask Letizia Jaccheri what got her interested in computer science as a young girl, she has two ready answers: The first is Pisa, the town in Italy where she was born. Here, engineers built Italy’s first home-grown computer, supported by entrepreneur Adriano Olivetti.

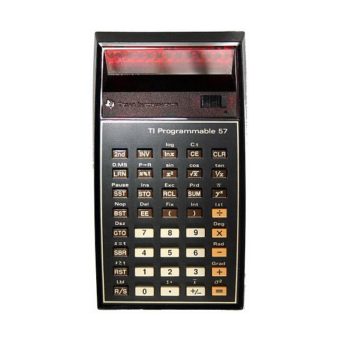

The second was a math teacher who taught her, as a 16-year-old, to program a simple handheld Texas Instruments calculator. It was such an important milestone that she even remembers the model number of the little machine, a TI-57.

The little programmable calculator that started it all, the TI 57. Photo: Wikimedia Commons, monster1000

“I have, over the years, reflected a lot about this journey,” Jaccheri said. But she has done more than simply reflect. Over the decades, along with her work as a professor of computer science at NTNU, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and as an adjunct professor II at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, she’s founded and nurtured a number of initiatives to bring more women into the tech industry.

On Friday, Jaccheri was selected as the 2021 winner of the Norwegian Oda Award Woman, which recognizes exceptional women who have made concrete contributions to increase diversity in the technology industry.

“Letizia Jaccheri is an impactful professor and role model. Through her work in academia and computer science she inspires female academics and young technology enthusiasts to take action,” the judges wrote. “Letizia inspires to lead the change. She is recognized for her ability to coach other women to take on bigger opportunities.”

The non-profit organization, which has more than 10,000 members and is supported by 50 different industry partners, says the winners of the award are “are good ambassadors for the values of ODA: Inspiration, Bravery, Empowerment and Passion.”

Creating an inclusive academic community

Anne Borge, NTNU’s rector, congratulated Jaccheri on her award.

“I wholeheartedly support the jury’s reasoning. As NTNU Rector, I would like to add that Letizia is one of our very best role models as a visible, brave and above all an outstanding scientist in a subject area that has traditionally been dominated by men,” Borg said.

Jaccheri’s own start in academia was at the University of Pisa, where she took a master’s degree in informatics and where nearly half of all her fellow students were women. She also had an exchange year at NTH, one of NTNU’s predecessors in 1989.

“Many of the professors, at least the young ones, were also female,” she said of her time at the University of Pisa.

When she was employed by NTNU in 1997, she found a university that wanted to improve its gender diversity and that had set up a number of programmes to ensure that more women were welcomed into technology-related fields.

“NTNU stated clear goals, employed an advisor for gender equality who worked full time for gender equality in academia,” she said. “NTNU started projects like The Girl Project Ada, which has been conducted for more than 20 years by several excellent project leaders and a generation of female students.”

Letizia Jaccheri shows girls that computer science isn’t just staring into a screen during a 2010 event to recruit girls to computer science. She’s showing them a coat she had developed that was connected to an Arduino processor, sensors and actuators. Photo: Private

The Ada project recruits female students for studies in computer science, communication technology, cybernetics and robots, electronic system design and innovation, informatics and mathematics. There’s early outreach for high-school girls, networking, and support to make sure that girls who are accepted to one of these academic disciplines don’t drop out.

Borg acknowledged Jaccheri’s positive effect on female recruitment via the ADA project.

“She has contributed greatly to encouraging many more girls to study ICT subjects than just a few years ago, both as a role model and through her active work in the ADA project,” Borg said.

Jaccheri herself has started and is involved in initiatives to increase diversity in the technology industry, including the IDUN Project, funded by Research Council of Norway and NTNU, Trondheim ACM’s Women in Computing Chapter, the European Network for Gender Balance in Informatics (EUGAIN) with participants from 38 countries, and the “Code Trail (Kodeløypa)” where young people learn about programming.

Why it matters

All these efforts have paid off.

“I have observed at my own Department of Computer Science the number of female students has grown from 6% in late 1990s to more of 30% master students and 50% PhD students in recent years,” Jaccheri said.

Across Europe, those numbers are less encouraging, she said. The European research project she’s leading, EUGAIN, shows that more than 80% of students enrolling or graduating with a bachelor’s degree in informatics are male; when it comes to PhDs from all but a handful of European countries, less than 25% of the graduates from ICT programmes are women.

Science and technology affect us all

Jaccheri said that it’s critical that society include women in all areas of research, but especially science and technology, because it makes a difference in people’s lives.

Making development processes more inclusive will result in more inclusive and powerful software products.

“My topic of research is software engineering. If the goal is to provide software that will improve the life for everyone in society, everyone has to be involved in the creation of the software requirements and the implementation, testing, deployment of software,” she said. “In technology, there are a number of examples of technology that provide solutions for men that do not work for women. We are changing this.”

Jaccheri’s own research is currently focused on how IT processes have to be changed to include more women.

“Making development processes more inclusive will result in more inclusive and powerful software products,” she said.

And even though Norway is making progress on meeting the goal of having women make up 40 per cent of the ICT workforce, Jaccheri says there’s much more work to be done, both in her adopted country and internationally. The two large research projects, IDUN and the European-wide project EUGAIN, should help with that.

“We have to evaluate the actions we are doing in the different countries, to compare, collate and develop efficient tools for speeding up the inclusion processes in computer science,” she said. “It is part of my plan to give back, not least to Italy, for the good education and the good start in life I have been so lucky to get.”