True crime in 19th century Norway

People have always been fascinated by real-life crime mysteries. True crime has become a popular genre in films, TV series, podcasts and books. The 19th century also had its own way of cultivating the genre.

Gjest Baardsen was one of Norway’s most notorious criminals in the 19th century and inspired a number of songs that many a Norwegian has heard or sung:

“And come if you want to hear a song about Gjest

It isn’t made for sheriffs and priests.”

Baardsen spent a lot of time in prison, but he was good at escaping. He was often compared to Robin Hood because he is said to have been concerned with the weak and poor, and was seen as a non-violent gentleman thief.

NTNU researchers Silje Haugen Warberg and Even Igland Diesen have examined Gjest Baardsen’s own evidence of his crimes. They have also studied songs about another of the 19th century’s major criminals: Ole Olsen Sevle, known as Sevle-guten.

He was a predatory murderer who was executed in 1834 after being on the run from the authorities for two years.

Songs about crimes and criminals originated in the heyday of the broadside ballad in the 19th century. The function of these songs was to convey stories, events and news to the common people. The genre was very popular.

NTNU has embarked on an extensive research project on Norwegian broadside ballads. Siv Gøril Brandtzæg is heading the project, the first of its kind to examine the significance of the songs for Norwegian cultural heritage.

Norwegian broadside ballads 1550 – 1950

- Norwegian broadside ballads have been disregarded in research and reduced to a footnote in literary history. This has in turn led to the texts having an unclear place in our national cultural history. The project shows that the broadside ballad is Norway's oldest mass medium, with a history that stretches back to the 16th century.

- In the early modern period, the texts functioned as an important source of news and entertainment, especially for the common people.

- The broadside ballads are part of Norway’s cultural heritage and are also among the oldest printed matter preserved in the Nordic countries, with a circulation history that stretches back to the 1550s and up to the 1950s.

- The impressive spread of the broadside ballads – in terms of their distribution, extensive duration spanning 400 years, and geographical spread from north to south and across the Scandinavian borders – also makes them one of the most popular genres ever to exist in this country.

You can read more here: https://skillingsviser.no/

Stomped the beat and sang his way to the scaffold

Silje Haugen Warberg is associate professor in the Department of Language and Literature and Even Igland Diesen is associate professor in the Department of Teacher Education, both at NTNU.

The researchers have examined a large amount of material in their work on the Sevle case, concentrating on the criminal stories about the Sevle-guten and the misdeeds he was responsible for. Ole Olsen Sevle gave his name to the Sevlen folk song.

The story goes that he must have written the song himself, and that he sang and stomped to the beat of the tune as he walked towards the scaffold.

Master thief Gjest Baardsen also wrote poems about himself, but often it was the prison chaplain, who prepared the condemned for punishment and death, who composed poems about the perpetrators and their crimes.

Fact or fiction?

The crime song genre encompasses a wide range of characters. They range from ambivalent fascination for a murderer like Sevle to the cultivation of a Robin Hood-like figure like Gjest Baardsen.

What the crime stories have in common is that they all contain an unclear distinction between what is fiction and what is fact.

The songs often dwell on precisely the parts we actually know the least about:

- What were the killer’s motives and thoughts?

- How did the victim experience his last moments?

- How did the condemned face the punishment?

True crime then and now

Accounts of true crime cases have fascinated audiences for hundreds of years.

“The development of crime fiction via folk literature’s crime stories to the modern true crime genre is an obvious thread to look at,” says Warberg.

True crime is a fact-based genre in literature, film, radio, podcasts and TV. In this genre, the writers or filmmakers investigate a real crime case and explore the circumstances and actions of people connected to the case.

The genre has become very popular all over the world and often deals with well-known and high-profile murder cases.

The genre relates to crime incidents from real life, but often uses narrative techniques with elements of fiction, such as conveying what the perpetrator was thinking.

Truman Capote‘s “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood (1965) is often considered the start of the true crime genre.

More about True crime

- Accounts of true crime cases have fascinated audiences for hundreds of years. In Great Britain, hundreds of pamphlets about murder were published in the years 1550–1700.

- In step with increasing literacy and more efficient printing methods, the pamphlets became more professional. Some of the pamphlets bore the stamp of sensationalism, while others had a more moral message.

- The pamphlets were particularly popular among the middle and upper classes, since the lower classes had neither the time nor the money to read them.

- The pamphlets continued well into the 19th century in Great Britain and the United States, until modern journalism took over.

- Over the years, stories, songs and ballads have also been composed about real criminal cases, including in Norway.

- From 1889 and in the decades that followed, the Scottish barrister William Roughead wrote and published histories of major famous British court cases. He is often considered the originator of the modern true crime genre.

- An American true crime pioneer was Edmund Pearson, who in the years 1924–36 published a series of books about various criminal cases. Several of the cases were also printed by magazines and weeklies such as The New Yorker and Vanity Fair.

- Truman Capote's “non-fiction novel” In Cold Blood (1965) is often considered the start of the modern literary true crime genre that made true crime books popular and profitable.

Source: https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/True_crime

Sevle-guten’s career

Documents from the trial and minutes from newspapers tell the story of Ole Olsen Selve, as do the broadside ballads that were composed in connection with his arrest and trial.

The available material says that Sevle-guten killed the itinerant peddler Toleiv Gjermundson Kittilsland, better known as “Sølv-Tollef.” Sevle-guten was also convicted of killing his own grandfather.

The grandfather, called Storen, lived on the family farm when Sevle-guten took it over in 1829. The grandfather had a farm pension contract which included the right to use property and other benefits.

A disagreement is said to have arisen after the grandfather remarried and wanted access to this entire pension amount. Sevle-guten and his father did not agree.

In 1830, the grandfather was found drowned in a pond.

Rumours quickly arose in the village that the grandson was behind the death.

Killer’s mind blackens

One of the songs describes the prelude to the murder, without emphasizing the financial motives that both the court report and later criminal narratives highlight.

In the song, however, the grandfather “chastised Ole and shamed him” when they were in a boat on the water. Ole’s mind darkens. This turn of mind is intensified by a clichéd weather metaphor that marks the prelude to the murder itself.

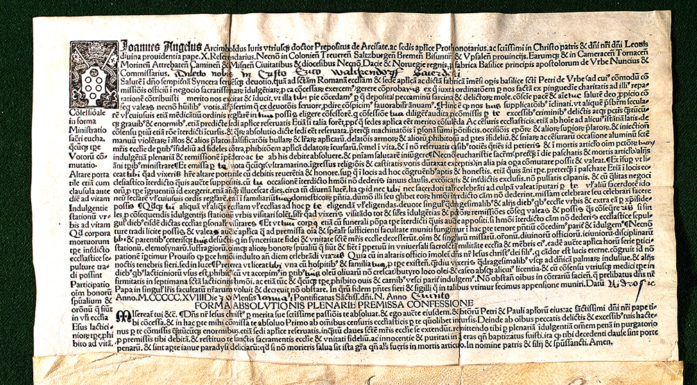

This image from the crime novel about Selve-guten was retrieved from the National Library of Norway.

The killer is described as both reckless and cold-blooded, and the story is rounded off with the omniscient narrator searching the killer’s mind.

Criminals’ childhoods are often held up as having been innocent, while their criminal career path is attributed to bad choices in adolescence.

In the Sevle song, however, the first stanza already establishes that he was inherently immoral and was “devoted to vice from his earliest years.”

Lack of remorse

Comparing the various representations in the Sevle songs, both with each other and with other texts about the case, it becomes clear that the representations mix rumours, information from the newspapers, established literary motifs and free poetry.

“Roughly speaking, the songs follow the information that was known about Sevle’s upbringing. Upon taking a closer look, however, we quickly discover that the view differs from the facts of the case on some minor, but significant points,” says Warberg.

Previous research into Scandinavian broadside ballads has concluded that the songs rarely provide completely reliable information about the cases they deal with.

“The songs have several parts that are obviously fictionalized, such as when we gain insight into Sevle’s thoughts. The fictionalized parts focus on Sevle’s intentions, motives and lack of remorse,” Warberg said.

Changed gender from male to female

To shed light on this complex relationship between fact, fiction and folksong tradition, the researchers took a deep dive into a Sevle song that was composed close to the event happening.

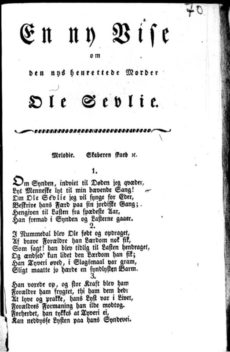

The text “En ny Vise om den nys henrettede Morder Ole Sevlie” (A new song about the recently executed Murderer Ole Sevlie) is part of the Norwegian Folklore Archives.

The content gives reason to believe that the song was originally composed on the occasion of Sevle’s execution in 1834, perhaps to advertise the event or even to be performed in connection with the execution.

The show opens with a direct appeal to its audience, who are asked to listen to the song about Sevle’s life as he “walks forward in Sin and Vice.”

In the course of twenty stanzas, the poem gives a comprehensive, condensed and simplified presentation of Sevle’s criminal career.

One element that illustrates the fiction in the story is that the victim is not called by his real name of Tollef, but is given the name Hellik.

Other changes from the facts are that a central witness has changed gender from male to female, as well as extended fictionalized sections that describe Sevle’s thoughts and pieces of dialogue, including between victim and perpetrator.

“We find this slightly fictionalized form of representation, where a lot is almost correct and the rest is made up or has been given a more dramatic touch, in many of the songs we’ve studied,” says Warberg.

Large collection of broadside ballads

The criminal tunes do not form a single category of broadside ballads. They can be divided into a number of thematic and genre subcategories, including:

- news songs released close to the time of the events

- narrative songs composed from a greater time distance

- farewell songs composed in connection with executions

- prison songs

The material on criminal songs from the 18th and early 19th centuries is dominated by execution songs. The last civil execution took place in 1876, changing the content of the songs.

The material that has been analysed was taken from the broadside ballad collection at the Gunnerus Library in Trondheim, the Norwegian Folklore Archives and the National Library of Norway’s digital collection.

Female criminals condemned, males treated like heroes

Most of the crime songs – and broadside ballads in general – are about men. When women are the focus of these songs, it is usually because they have killed their newborn infant or less often, their husbands or parents.

Women murderers are unequivocally condemned.

“In representing male criminals, we often find an ambivalent approach to the criminal, a figure who is both repulsive, fascinating and impressive. When his exploits are recounted in criminal songs and other traditions, the ambiguous hero figure is created,” says Diesen.

“This unclear relationship between fantasy and reality that characterizes the broadside ballad tradition is precisely what has contributed to keeping the stories of criminals like the murderer Ole Olsen Sevle and master thieves Gjest Baardsen and Ole Høiland alive,” he says.

Reference: Silje Haugen Warberg, Even Igland Diesen. Forbrytelsens fascinasjon og fiksjonalisert (selv)- framstilling i 1800-tallets forbryterviser. The fascination with crime and its fictionalized (self)-presentation in 19th-century criminal songs.