Digital help might be better for children with OCD

For some children with obsessive-compulsive disorder, therapy via the internet and apps can be more effective than physically attending treatment sessions.

New research is good news for children and families who live far away from the nearest treatment centre – or if a new pandemic emerges.

“The new tools enable more flexible and varied ways of treating children who struggle with OCD. We see a lot of advantages in both the therapy and follow-up sessions, when the patient is at home or in their wider environment where the compulsive behaviour occurs. We can also reach many more patients this way,” says Lucía Babiano-Espinosa, a psychologist who recently obtained her doctorate at NTNU’s Department of Mental Health.

Lucía Babiano-Espinosa focused her PhD on how treatment with a webcam and an app (eCBT) can be just as effective in treating OCD for some children as physically attending treatment sessions. Photo: Sølvi W. Normannsen

Babiano-Espinosa is part of a project group that is developing technology-based improvements to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder. Through her doctoral project eCBT (Enhanced Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in Children and Adolescents), the researcher has followed 25 children and adolescents aged 7-18 over a three-year period.

Many patients overcame their ailments

All the project participants received treatment via webcam and a mobile app in addition to some meetings in person. The results are encouraging.

The patients liked the treatment, no one dropped out during the course of treatment, and the therapists found the methodology easy to use.

And most importantly: Many of the youngsters eliminated their OCD symptoms.

The researchers compared the results of the 25 patients with the results of 269 patients who had previously received traditional treatment with physical sessions. It turned out that 68 per cent of the patients who received online therapy responded to treatment, compared to 60 per cent in the other group. Furthermore, the eCBT group reduced their symptoms by 64 per cent, compared to 53 per cent in the group that received traditional therapy.

Often discovered around age 11

Some obsessive-compulsive disorders involve an extreme urge for order and symmetry. Photo: Colourbox

The patient group that Babiano-Espinosa followed consisted of both boys and girls – quite ordinary children and teens from villages and towns – who share a diagnosis of OCD.

According to the psychologist, between one and three per cent of the population develops obsessive thoughts and behaviours. Obsessive-compulsive disorder affects both boys and girls, and occurs in all countries and ethnic groups. Often the first symptoms appear when children are around 11 years old. For many, the disorder can control everyday life completely, and it can become a major strain on the family.

Symptoms can vary considerably. One symptom that many people have heard of is a fear of bacteria, where patients try to avoid infection by washing their hands frequently, intensively and for a long time. Others believe that certain behaviours can help them achieve something they want – or the opposite, that they can avoid illness or disaster by performing specific actions.

Behaviours to achieve – or avoid – situations

“These ideas can become an obsession, and the actions become a way of dealing with them. They develop into rituals that are repeated, such as: If I turn the light on and off 11 times, then we’ll win the football match next week. Or, if I open and close this door seven times, mum and dad won’t get cancer and die,” says Babiano-Espinosa.

“The behaviours provide a short-term reward, in the form of anxiety relief. But in the long term, they cause the anxiety to intensify.”

The therapists work with the children to teach them to accept that much in life is scary, that things can happen outside of our control. They do this using exposure therapy, where they gradually expose patients to things that they experience as unpleasant.

Treatment sessions where behaviours occur

The patients had several face-to-face meetings with the psychologist in the office setting. The meetings via webcam took place while the children were at home or at school.

“These places are often where the OCD behaviours take place. It’s easier for patients to show us their rituals where they actually do them than to recreate them in the office. And it’s easier for us to get a picture of what they’re telling us,” says Babiano-Espinosa.

Some therapy sessions only last a few minutes. For example, pupils can connect from school, in front of the student’s neatly organized bookcase. The therapist might ask: “What happens if you move that book over a little bit?” or “What if you place it perpendicular to the others?”

A patient who can’t stand anyone touching his bed can show the therapist around his room and the therapist could suggest: “What would you think about letting your mum come in and just touch the very edge of the bed, really quickly?”

“The method also means that we don’t need to interrupt the treatment during holidays and the like. I met some patients via webcam while they were abroad, and they were able to show me that they were working on themselves, like touching their fingers on the ground,” says Babiano-Espinosa.

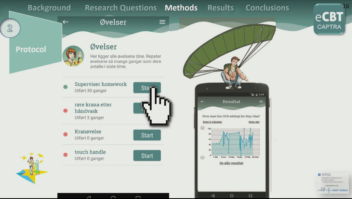

App with exercises and rewards

Between therapy sessions, patients used the mobile app where they have their own personal room, including a list of symptoms. They can also enter symptoms themselves, and enter numerical values for how stressful they find the various obsessions.

The app also contains videos, such as Tom (13) talking about his battle with walking over cracks and lines, Liv (15) who talks about dance, OCD and bacteria and Jan (17) who talks about strange thoughts and troublesome numbers. There is also a mother who shares how OCD affects the whole family. The children’s guardians also have the app, but some information remains confidential between the patient and the therapist.

The therapist enters exercises to be repeated a certain number of times, like leaving pencils criss-crossed on top of each other on the desk, or holding a doorknob for 10 seconds.

The therapist enters exercises to be repeated a certain number of times, like leaving pencils criss-crossed on top of each other on the desk, or holding a doorknob for 10 seconds.

When the exercises are completed, they go from red to green on the task list. Along the way, patients receive small digital rewards and encouragement. If they want, they can also describe how it feels to do the exercises.

Hope the research makes a difference

“Technology and apps are the home ground for youth. They’re digital citizens. It’s a good idea to use the tools that the new generations take for granted,” says Babiano-Espinosa.

Other possible advantages of eCBT are that it takes less time and cost to travel. For some people, seeing a psychologist can be a stigma, which becomes less with digital treatment.

“All of these reasons, plus the fact that Norway is a country with widely scattered settlement, mean that online treatment can be useful for reaching children who live far away – or in the event of a new pandemic,” says the psychologist, who hopes that the research and methods can eventually be put to use in hospital.

Babiano-Espinosa defended her doctorate on 13 January 2023.

eCBT: Online treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder

- eCBT stands for "Enhanced Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) in Children and Adolescents."

- Lucía Babiano-Espinosa's PhD on the topic is based on four peer-reviewed articles and a cover letter (summary).

- In an article published in 2019, the research group had found only six international studies that dealt with online treatment of children with OCD. A few more studies have been published since then.

- To date, the eCBT project has published data through six months following treatment.

- Work is now underway to add the most important functions of the eCBT app to the app HelsaMi.

- The project group is now working on a study of patients who received 100 per cent online treatment during the COVID pandemic.

Watch a video that summarizes the article:

Reference:

Lucía Babiano-Espinosa, Gudmundur Skarphedinsson, Bernhard Weidle, Lidewij H.Wolters, Tord Ivarsson, Norbert Skokauskas.eCBT versus standard individual CBT for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development (2022)

Watch this video where Babiano-Espinosa explains her research at Trondheim’s TEDx 2021.