Living near a glacier is like having a helpful but unpredictable neighbour. As the climate becomes warmer, the risk of unruly behaviour from these neighbours increases. A group of researchers wants to help communities living close to melting glaciers.

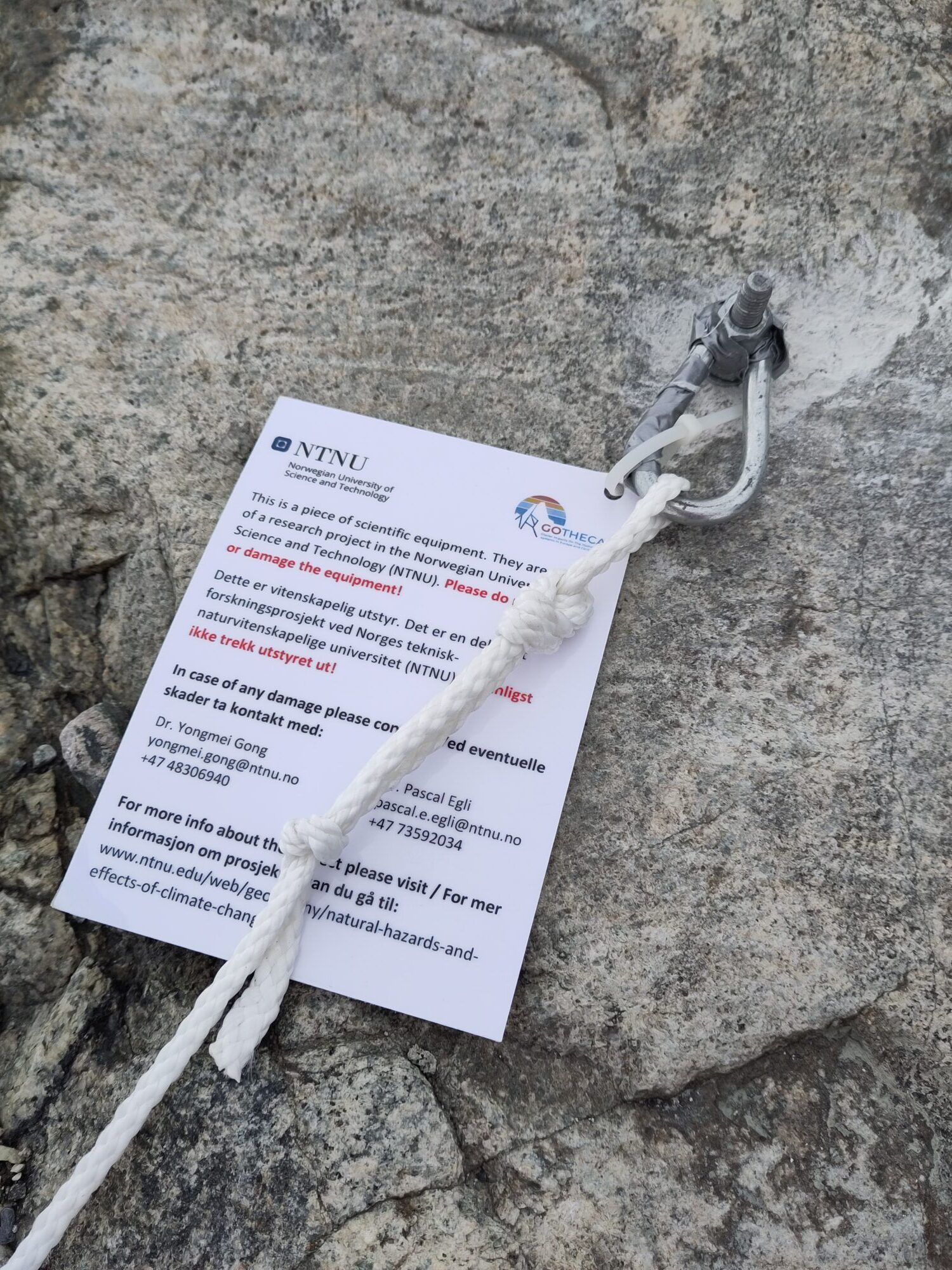

Photo: Yongmei Gong

The glaciers' warning

Av Sølvi Waterloo Normannsen - Publisert 13.10.2023

Mountain ranges are often described as the planet’s water towers.

Glaciers are enormous stores of fresh water in the form of densely packed snow and ice.

They are vital sources for local communities, hydropower, agriculture and tourism.

Glaciers around the world are now melting.

The ice is retreating, causing floods.

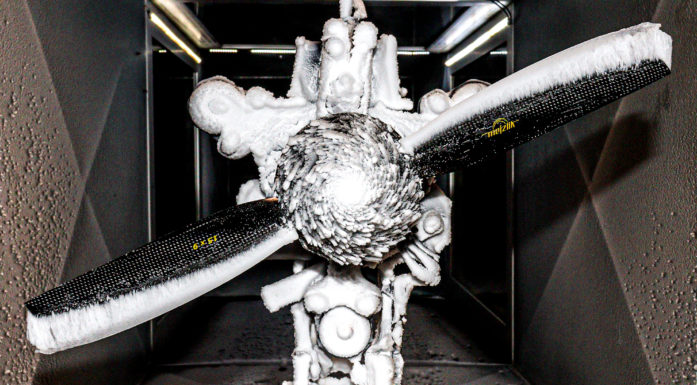

Video: Yongmei Gong

Interaction between climate, glaciers and society

Glacier-dammed lakes are lakes that are dammed by glacial ice and filled with meltwater and precipitation. They often form in the side valleys of a glacier, between the ice and the bedrock.

The water level in glacier-dammed lakes can vary rapidly and greatly. Sometimes, a glacial lake can be completely emptied in just a few hours. If a glacial lake is large, this sudden discharge of water can lead to catastrophic glacial flooding. These types of outburst floods are called jökulhlaups.

“A jökulhlaup can threaten and destroy communities located downstream. In Norway, the danger is not as great as in other parts of the world, but devastating glacial outburst floods have also occurred here,” says Yongmei Gong, a researcher at NTNU’s Department of Geography.

She is a glaciologist and head of the GOTHECA-NOCK project. The project monitors three glacial systems in Norway and one in the Karakorum region located between China, India and Pakistan.

The aim is to understand the interaction between the climate system and changes in glacier-dammed lakes, and how this affects local communities and infrastructure.

THIS IS GOTHECA-NOCK (2022-2025):

Glacier impacts On The Hydrological systems in Europe and Central Asia - A pilot study of drivers and societal impacts of freshwater discharge from glacial systems in Norway and the Chinese Karakoram.

The project takes a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to the interaction between climate, glaciers, water cycles and local communities.

The goal is better risk assessments and advice for adaptation to climate change in glacial areas.

The work includes modelling of ice dynamics and subglacial hydrology, monitoring of glacier-dammed lakes, hydrology in the catchment areas, and meteorological measurements.

Human geography and planning, use of natural resources, and natural hazards and geohazards are also included.

An additional goal is to develop common methods and systems that can be used on a large scale – in Norway, in Europe and in Central Asia.

Funded by the Research Council of Norway’s Programme for Young Research Talents.

A total of six researchers at NTNU’s Department of Geography and two researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences are participating.

Partners from the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences and GRID Arendal also have one researcher each participating in the project.

One reason why the risk of violent flooding is not so great in Norway is that floodwater flows into reservoirs and is used to produce hydropower.

In some places, tunnels have been built through the mountains that drain or divert the water away.

The biggest concerns in Norway are related to whether climate change could threaten power production.

The biggest threats are excessive flooding that can destroy power plants and infrastructure, or from hot and dry summers that don't provide enough water to meet electricity demands.

Photo: Shutterstock

Melting glaciers affect people’s lives

The changes stress the economy and ecosystems.

New melting patterns affect both the availability and quality of fresh water. Local tourism can be affected, and fluctuating runoff water impacts seasonal agriculture and people’s livelihoods.

As glaciers retreat, they become harder to reach, they can collapse, and become more dangerous for researchers and tourists.

The researchers are monitoring these glacial systems and collecting data to create models that can describe and predict the behaviour of glaciers and glacial lakes.

Gotheca-Nock combines natural and social sciences.

The researchers are interested in how the local population views what is happening.

Local communities must be equipped to assess and manage the risk that these glacial systems pose.

The authorities must be helped to ensure they make the best possible decisions.

Everyone must adapt, tolerate, and cope with what is coming.

Photo: Pascal Egli

All of the glacial systems the researchers are studying have glacier-dammed lakes.

They have all caused devastating outburst floods.

There is a risk of this happening again.

Photo: Ursula Enzenhofer

Jökulhlaup and flooding

A jökulhlaup is a sudden discharge of large amounts of water from a glacier.

The water may come from a glacier-dammed lake, a moraine-dammed lake, or water that was stored under or on top of the glacier.

In Norway, most of the jökulhlaups that occur come from glacier-dammed lakes.

Once water starts to flow beneath the glacier, melting and erosion quickly widen the channel so that the flow of water out of the lake increases rapidly.

The lake can be fully or partially emptied in a very short period of time leading to massive flooding.

These types of floods can cause major damage.

This is Rembesdalskåka, a glacier arm from the mighty Hardangerjøkulen glacier.

The glacier dams the Demmevatnet lake.

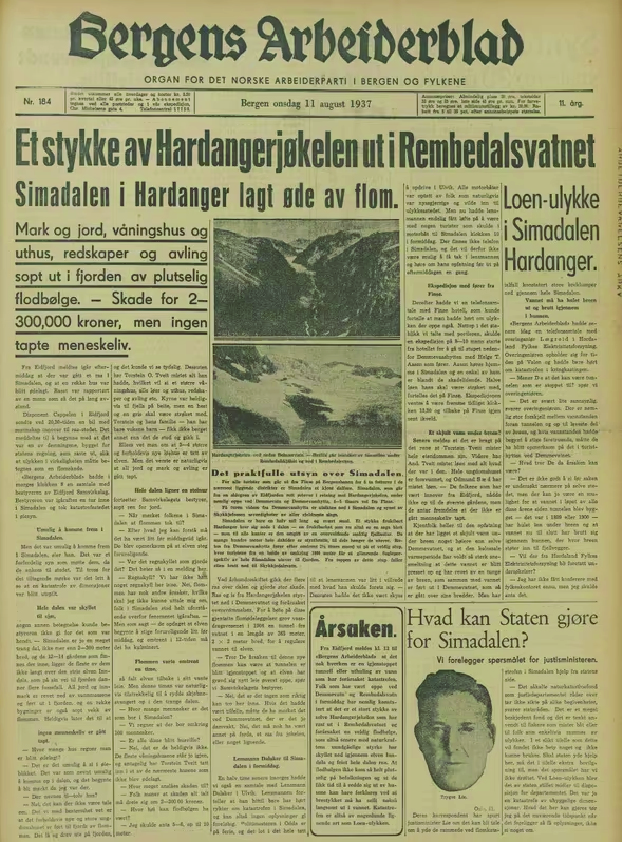

This is where Norway’s most destructive jökulhlaup occurred 86 years ago.

The natural dam gave way.

Huge amounts of water were discharged, gushing down Simadalen valley and destroying everything in its path.

Foto: Yongmei Gong

When the water lifted the glacier

There was no warning about the disaster waiting to happen up in the mountains above Simadalen valley on 10 August 1937.

No one saw the forces at work beneath the glacier-covered landscape.

The sun shone. The ice melted. The water rose and pushed its way forward. It made a channel and lifted up the glacier. Slowly, but with tremendous force, millimetre by millimetre.

Finally, the natural dam burst, and all the water gushed out.

NRK has described how the river, which was normally 30 metres wide, grew to a width of 300 meters in just a few hours. At several locations, the water level rose by 20 metres. The flood washed away bridges and roads, the landscape was razed, and all 20 farms in the village were affected. Incredibly, no lives were lost.

Jökulhlaups have occurred many times here throughout history. After a major flood in 1893, drainage tunnels were built through the bedrock. Their purpose was to prevent the water from rising so high that it lifted the glacier up again. Everything worked well, until the disaster in 1937.

Since then, Rembesdalskåka glacier and Demmevatnet lake have not caused any problems. Downstream, Statkraft has built Sima power plant. This is Norway’s second largest power plant, measured by output.

The lake empties itself every year. The water level can vary rapidly and greatly. Occasionally, an abrupt, complete discharge of water can occur in just a few hours.

Tunnels, reservoirs and power plants have kept the water masses in check and prevented flood damage.

However, something has started to happen again under the ice high up in the mountains. In late August 2014, a new jökulhlaup occurred from Demmevatnet lake as a result of the glacier’s retreat.

Almost overnight, two billion litres of water disappeared through the ice.

The lake was completely emptied.

The water had accumulated in Rembedalsvatnet lake further down the valley.

In 2015, a collaboration began between the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) and researchers from the Department of Geography at NTNU.

The researchers are monitoring the glacier system closely. They collect data and develop computer models that can show and explain what is going on.

Since 2016, a jökulhlaup has occurred from Demmevatnet lake every single year.

Photo: Yongmei Gong

At the end of April, glaciologists from NTNU once again made their way to the Rembesdalskåka glacier.

This was the first of this year’s field trips.

Data capture was on the to-do list. This involved installing a webcam, a weather station, measuring snow depth, snow profiles and various other things to achieve the best possible monitoring of the glacial lake.

Fieldwork on glaciers involves long trips transporting heavy sledges.

The weather can be wild and changeable.

The work is hard, in challenging terrain.

Glaciologists Ursula Enzenhofer, Ronja Lappe, Sangita Tomar, Pascal Egli, Yongmei Gong and the others were rewarded for their efforts.

Photo: Yongmei Gong

Early discharge of water

Usually, Demmevatnet lake begins to empty in late summer. This year, however, things were different.

A few days after the camera was installed and the researchers had left, the glacier began to melt.

The water in the lake began to rise, and then it emptied abruptly.

Yongmei Gong said she was sitting in a café with a cup of coffee in one hand and her mobile phone in the other. She checked the webcam and almost choked on her coffee.

In just a few hours during the night between 21 and 22 June 2023, Demmevatnet lake had dried up completely.

This was the first time in 7 years that it happened so early in the year.

“We were incredibly lucky to be able to capture everything on camera,” says Gong.

This is Demmevasshytta cabin, one of the oldest cabins belonging to the Norwegian Trekking Association.

Next door is a simple but unique laboratory.

From here, researchers can monitor the movements of the Rembesdalskåka glacier.

According to NVE, the glacier retreated 380 metres from 1997 to 2020.

100 years ago, the glacier arm was right below the steps of the cabin.

Photo: Yongmei Gong

More unpredictable

The GOTHECA-NOCK project will run until 2025. Next year, NTNU researchers will conduct fieldwork in the Karakoram mountain range between China, India and Pakistan.

In this arid mountain region, the glaciers are primarily sources of freshwater. Several jökulhlaups have occurred here in recent years. Entire villages have been wiped out or completely isolated by sudden glacial floods.

“With more extreme weather on the way, you never know how big the floods might be,” says Yongmei Gong.

More dangerous or less dangerous?

As the glaciers retreat, the glacial lakes get bigger. The big question is whether they will become more dangerous or less dangerous.

Gong combines models of ice dynamics and subglacial hydrology with data on precipitation, wind and temperatures from global climate models.

This enables her to estimate how the geometry and shape of a glacier will change as a result of climate change, and how jökulhlaups develop beneath glaciers.

The models project what sort of flooding we can expect, depending on whether we do a lot, a little, or nothing to curb CO2 emissions.

What do people in the villages think about the glaciers disappearing?

How are they adapting?

What about the tourists who come to see and walk on the blue ice?

“Many foreigners are visiting Norway now to experience the glaciers before they disappear. There is a kind of last-minute tourism going on. It is interesting.

“A lot of young people actually tell us that the mountains are more important. If the glaciers disappear, the mountains will still remain.

“I sometimes wonder if foreigners romanticize the glaciers more than Norwegians do.

“People in the Alps are dealing with this in a completely different way. There, they are trying to save the glaciers by covering them with blankets and hold funerals for dead ice. I don’t know whether the people I have spoken to are unique optimists, but some of them simply say that we should enjoy the glaciers while they last.

And when the glaciers are no longer there, they will continue to hike in the mountains, Gong says.

There are just over 2500 glaciers on mainland Norway.

Svalbard has around 2100.

Although there are fewer glaciers there and not many settlements located close to the glaciers, most of the research has taken place in Svalbard.

"That's why we now are turning to the glaciers on mainland Norway. We want to contribute more practical knowledge that can help people and communities adapt to climate change," says glaciologist Yongmei Gong.

Foto: Ursula Enzenhofer

The researcher says she has the impression that people get depressed by all the warnings the scientists give.

"The fear that everything will melt and disappear can take away people’s hope for the future. Some people get depressed, some don’t believe us, while others become climate change deniers.

"As researchers, we have a great responsibility. I don’t want to simply press the climate change alarm button. I want to communicate that we are gathering knowledge that will allow us to adapt and continue our lives even if the glaciers disappear, Gong said.

Foto: Ronja Lappe

MORE NORWEGIAN SCITECH NEWS

LOADING CONTENT