Scientists are revealing the secret lives of bees using sensors

Bees do more than just pollinate plants. They are also nature’s own warning signal. Placing sensors in their hives allows researchers to see when the bees need help doing their job.

When bees are doing well, they produce a lot of honey. When they aren’t doing well, their production drops. Femke B. Gelderblom, a senior research scientist at SINTEF, explains how straightforward bees’ signals can be.

A digital scientist who works with agriculture? You bet: this project also involves acoustics, sensors and artificial intelligence. Gelderblom and project owner Beefutures are helping bees with technology so advanced that the bees will never understand it – and most people won’t either.

Nature’s own sentinel

Bees do more than just pollinate plants. They also serve as nature’s own sentinel. A bee colony’s daily foraging trips can cover up to 700 hectares. Along the way, the bees create millions of data points that modern sensors and artificial intelligence can capture for scientists to analyse what is happening. Bees are thus an important key to monitoring the environment.

Bees and hobbits

- HoBBIT stands for Honey Bee monitoring with Bioacoustics and Imaging Technology.

- HoBBIT is a project that will develop methods for using sensors and artificial intelligence to better understand bees and the environment – with the help of bees.

- Project owner Beefutures, SINTEF and NINA – the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research – are collaborating on the project.

- The project will last until 2029 and is supported by The Research Council of Norway.

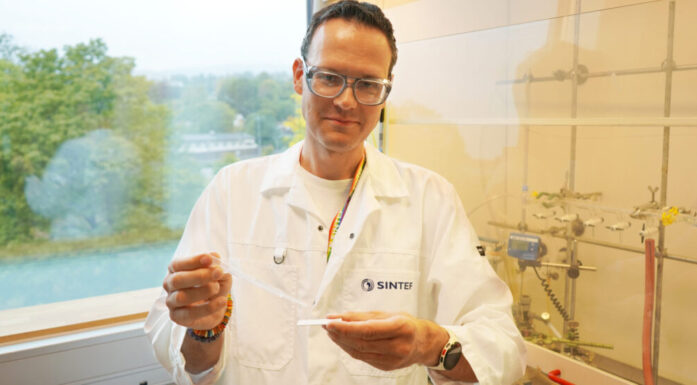

Gelderblom mainly works with artificial intelligence and sound. Bees make different sounds when the hive is without a queen, for example. Photo: SINTEF

The bees’ behaviour quickly reveals when they are not feeling well. They produce less honey, but they also move differently and make different sounds. Sensors installed in the hives enable researchers to see when the bees are struggling and to intervene before the consequences become serious.

No bees, no food

Gelderblom’s concern for the bees is about more than survival. They need to be able to do their job, too.

“Bees are extremely important for the food supply. Agriculture needs bees that ‘work on assignment.’” So farms have one type of honeybee that has been domesticated, which does the job that agriculture wants and pollinates what they grow. We need to know the effect of agricultural practices on the bees,” she says.

“Everyone understands that when the bees are on site, you shouldn’t spray with insecticides. But then there are a number of other chemicals, like fungicides. Apples, pears and plums in particular are treated with fungicides to prevent them from starting to rot. The chemicals aren’t supposed to be harmful to the bees. But is that really the case? We will study this,” says Gelderblom.

Data stream that sees, listens and weighs

Gelderblom and her collaborators conduct this research using a special sensor platform that they mount under ordinary hives. The platform has a camera, microphone, scale and sensors that monitor humidity and temperature.

Researchers don beekeeping equipment to check that everything is in order in some hives in Drøbak. Photo: Femke B. Gelderblom

The result is a continuous stream of data. Videos indicate whether the bees are scratching because they are being attacked by mites. Microphones reveal how the sounds in the hive change when the queen is missing. Temperature measurements tell whether the bees are able to maintain a stable ideal temperature of 35 degrees in the hive.

“We’ve seen videos where the bees come in and start busily scratching themselves, an indication that they have an infection from a mite,” says Gelderblom. Usually it’s the Varroa mite, a common parasite with the dramatic Latin name Varroa destructor.”

“We can also see on the camera when the bees seem a little confused. Then we listen to them with the microphones. When the queen is gone, for example, the entire colony becomes less efficient, and they also make different sounds,” she Gelderblom.

The researchers have come a long way with their sensors, and they use artificial intelligence to analyse the large amount of data that comes in.

- Here you can see when the camera films the bees and records how they behave.

“The temperature and how much honey the bees produce are clear indicators, but not necessarily the first signs. We would prefer to detect when something is wrong as soon as possible,” says Gelderblom.

Connecting AI and beekeeping

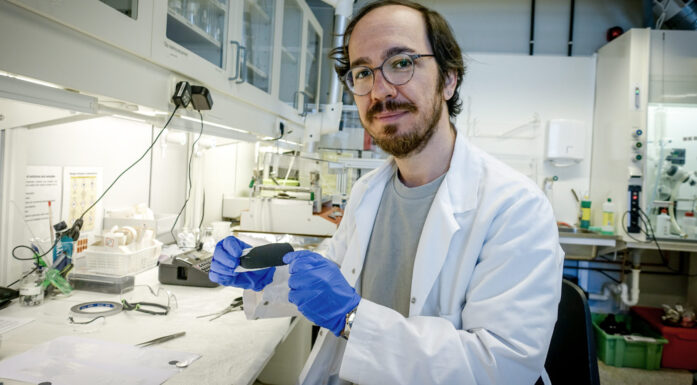

Christophe Brod is the general manager at Beefutures, and he says that sensors that monitor the bees are nothing new.

Solar cells and mobile networks ensure that the monitoring work can be carried out continuously. The light grey base below the green beehives is the platform that contains the sensors. Photo: Femke Gelderblom

“Soon we’ll celebrate our 20th anniversary. But bees are dying faster than ever, and digital beekeeping has not yet fulfilled its promises,” notes Brod, who left his career as an engineer to focus on beekeeping.

Today the company is based in the Oslo Science Park.

Brod wonders, “Maybe technology’s contribution should not primarily be to manage bees more efficiently, but rather to help us find the reasons for why there are fewer bees? And helping us understand what environmental stressors mean for the ecosystem.

He is a great believer in artificial intelligence, which can now monitor audio recordings and video continuously. Audio and video from the beehives can be sent out for AI analysis using solar energy and a connection to the mobile networks that are now found in almost all places where there are beehives.

“We can monitor traffic from the hive entrance, listen to the surroundings and track how the bee colonies react to climate events and human activities. We can also look at what is happening around the hive area in terms of flowers, birds and invasive or harmful species. Each beehive can become a monitoring station for the local ecosystem,” says Brod.

- Read more on the HoBBIT project page