What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

How will a warming Arctic affect plant growth on Svalbard? Researchers encased plant plots in a thick layer of ice during the winter and used little greenhouses to heat up those plots in the summer. The surprise? The plants that got the harshest treatment did just fine.

For five Januarys starting in 2016, researchers and students from NTNU travelled to a small valley outside of Svalbard’s main city with big jugs of liquid water and an unusual goal: To encase selected plant plots in a thick cover of ice.

Their focus was a plant community dominated by the polar willow, a critical year-round food for Svalbard’s reindeer population.

They wanted to see what happens to these plant communities during winter weather extremes, where prolonged rain instead of snow can freeze the ground solid and encase plants in a thick icy cap – right until spring melt.

Over the five years, we don’t see any accumulated effect, which means that the community is actually very resilient to icing.

But to make the experiment truly reflect what will happen as the Arctic warms, some plant plots during the summer were encased in little open-top plexiglass greenhouses.

The greenhouses made the plots warmer than the environment around them, simulating the higher temperatures that are expected on Svalbard as the Arctic continues to warm.

You might think that being frozen in a block of ice followed by being warmed in the little greenhouses might mean the end for these plants.

But much to their surprise, the researchers found quite the opposite effect.

Summer warming counteracts effects of winter icing

“If you sum up what happened throughout the entire growing season, you actually had more above-ground production (in the frozen and then warmed plants) than plants in the control situation,” said Mathilde Le Moullec, a researcher at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and at NTNU.

She was the first author of a paper about their findings, just published in the Journal of Ecology.

So what does that actually mean?

Biologists here use the word production to describe everything a plant produces above-ground during the summer growing season, from leaves and branches, to flowers and seeds.

More production generally means that the plant is stronger, can make more reserves to survive another winter, expand the amount of ground it covers and produce offspring.

In this case, the plants that got encased in a thick covering of ice, along with extra warming in the summer – were the winners.

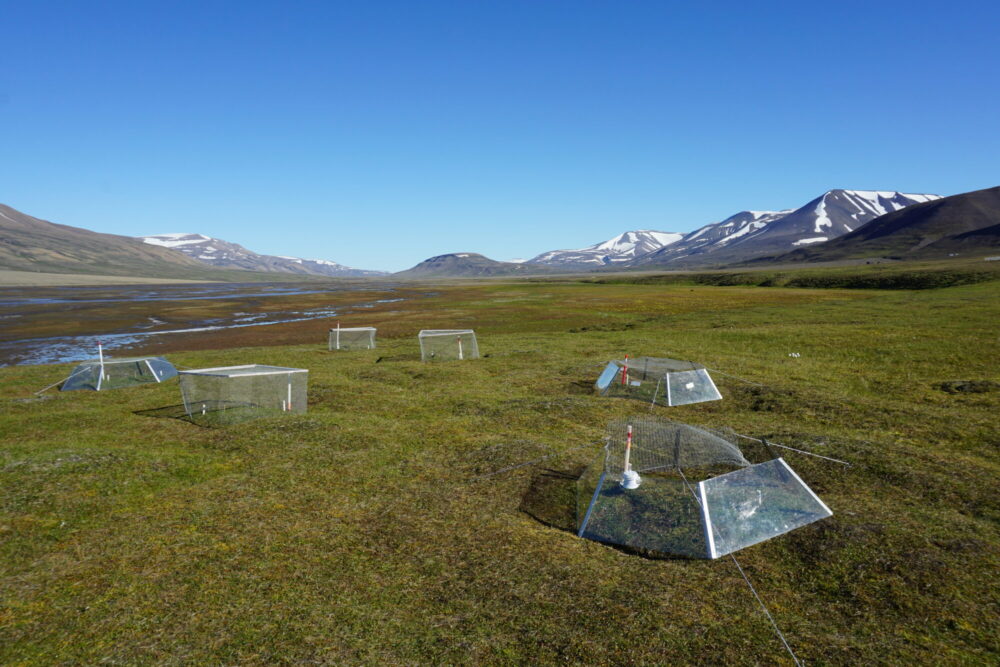

Here’s what one of the three experimental sites looked like in Adventdalen. The plexiglass frames around some of the plots were designed to simulate warmer temperatures. Plots that didn’t have the plexiglass enclosures were protected from grazing reindeer to prevent the animals from eating the scientific evidence. Photo: Mathilde Le Moullec

“More above-ground production also means more forage for reindeer in summer and fall, allowing them in turn to build up reserves to survive the winter. This also matters because winter ice can possibly encase these plants, which can make them inaccessible to reindeer,” said Brage Bremset Hansen, a professor at NTNU’s Gjærevoll Centre and a senior researcher at NINA, the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

The research set-up

Researchers wanted to compare two different known consequences of a warmer Arctic: freezing rain, which can cover plant communities in a thick icy cap that will persist until spring, and warmer summer temperatures, which could in theory stress arctic plants.

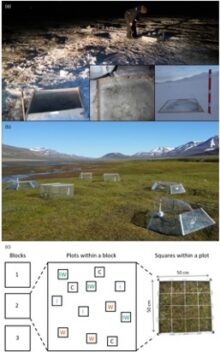

[caption id="attachment_87005" align="alignright" width="220"] The experimental set up in the Adventdalen valley, Svalbard. Overview of the field site (a) in the polar night, (b) in summer with the open top chambers simulating warming and net cages to prevent herbivory. (c) Experimental nested design C = control, I = icing, IW = icing × warming, W = warming. Picture credits: Ø. Varpe and M. Le Moullec.[/caption]

The experimental set up in the Adventdalen valley, Svalbard. Overview of the field site (a) in the polar night, (b) in summer with the open top chambers simulating warming and net cages to prevent herbivory. (c) Experimental nested design C = control, I = icing, IW = icing × warming, W = warming. Picture credits: Ø. Varpe and M. Le Moullec.[/caption]

So they established three research areas in Adventdalen, with each area or block containing a total of twelve 50x50 cm plots. The twelve plots in each block were divided into four different treatments, so that each treatment was applied to three plots:

The first treatment was to do nothing, and leave plots in their natural state. These are called controls, because they let researchers know what would happen naturally.

The second treatment was where plots had a 60cm by 60cm wooden frame around them, which was repeatedly filled with water in January to create a 13-cm-thick layer of ice.

The third treatment was where plots were encased with an open-topped plexiglass chamber after snow/ice melt to simulate global-warming induced warmer temperatures.

The fourth treatment involved icing the plots in the winter and encasing them in the plexiglass chamber in the summer.

Timing important, too

But what about timing – when plants produced their leaves, flowers and seeds?

Timing matters because arctic summers are so short, flowers and seeds that are produced too late in the summer will not help the plant reproduce. Here, the findings were mixed.

The polar willows that had only been encased in ice were delayed in opening their leaves, because it took longer to thaw the soil. But they eventually sped up their development. Nevertheless, they had smaller and thinner leaves than the control plants.

Here’s a look at the seasonal life cycle of female flowers of Salix polaris, the polar willow. From left, the plant has emerged from its winter dormancy with buds that are ready to open as the temperatures warm. Next, the leaves and flower buds emerge, and then the tiny flowers open, with the last two photos showing the red catkin and the long hairs that facilitate seed spread. Photo montage: Mathilde Le Moullec

The plants that had only been frozen also didn’t make as many flowers and were late with making seeds.

But the plants that had been frozen and then warmed – they were supercharged. Their production exceeded and was earlier than the controls. Their seed dispersal was also advanced, even more than the plants that weren’t subjected to freezing and were only warmed in the little greenhouses.

The main drawback, it seemed, for all the plants other than the controls was that they produced fewer flowers.

However, Arctic plants mainly reproduce asexually, through cloning or expanding rhizomes, so less flower production may not be that critical, as long as a few seeds survive and are dispersed at the right time, Le Moullec said.

Five years of consistent freezing

Researchers try to design experiments out in the field that mimic as closely as they can the environmental changes they’re trying to understand.

In this case, Le Moullec and her colleagues had to think carefully about the 50×50 cm plots that they planned to freeze. They had to hold the water in place as it froze somehow. In the end, however, they decided to surround the plots with 60×60 cm frames.

In real life, however, the layer of ice might be much more extensive than that and cover an entire valley. And the researchers knew that sometimes the ice could be much thicker than the 13 cm thickness they used.

Mathilde Le Moullec pours water into a plot where she and her colleagues were simulating what happens in Svalbard when rain freezes and encases the soil and plants in a thick layer of ice.

Photo: Iselin Helløy

That matters because plants do actually “breathe” – not like humans, of course, but they take in CO2 and release oxygen in the process of photosynthesis. In winter when there is no light and they’re not photosynthesizing, they need oxygen to maintain their cells in a healthy state. So if they’re frozen in an extensive layer of ice, they might be at risk of anoxia – suffocating.

Nevertheless, after five years of consistent freezing, they didn’t encounter this problem.

“Over the five years, we don’t see any accumulated effect, which means that the community is actually very resilient to icing,” Le Moullec said. “And when you see what we do to them, that’s a surprise.”

More to learn about a surprisingly resilient system

This is now the 11th year where researchers have visited Adventdalen in the winter with big jugs of water to simulate the effects of winter rain and frozen soil on Svalbard plants. Hansen says the plan is to continue to return to the plots and redo the measurements. The goal is to better understand potential long-term effects of a warmer Arctic on these plant communities.

Even as the Arctic warms, it remains an unforgiving environment for plants and animals alike.

“Arctic vegetation communities are exposed to a huge amount of variability, with lots of changes in when the spring onset is, and with winter conditions,” Le Moullec said.

The polar willow community, however, “ is a surprisingly resilient system,” she said.

Reference:

, , , , , , , , , & (2026). Towards rainy high Arctic winters: How experimental icing and summer warming affect tundra plant phenology, productivity and reproduction. Journal of Ecology, 114, e70234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.70234