Digital care

If a car tilts, a sensor beeps, and our mobile phones alert us when the battery gets too low. But who gets notified if grandma falls? Or who checks her blood pressure daily?

I am doing very well and managing nicely at the moment with my security alarm and telephone”, says 91-year old Ellen Owesen in Trondheim. Like many others of her age, she enjoys living alone. Her home is built to universal lifespan standards. It’s easy for her to get out with her wheeled walker, and during the bright summer days she often takes a stroll down to the local grocery store.

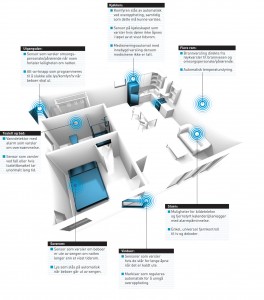

Greater security at home

This is how a comprehensive security system using smart house sensors might look like.

Graphics: Ivar Gaasø/VG

And 75-year old Astrid Nøklebye Heiberg, former professor, doctor, State Secretary at the Ministry of Social Affairs and President of the Norwegian Red Cross, is certain that many elderly people would prefer to live at home for as long as possible, if they could only have a little day-to-day help and someone to keep an eye on them. Speaking for herself, she says she is an enthusiastic fan of technology.

“If I fall on the bathroom floor and can’t get up, I want someone to be notified. And I’d rather have a GPS or sensor around my neck than to get lost when my memory goes,” she says.

She knows that to use this technology, you have to get informed consent from the individual concerned, but believes the norwegian Directorate of Health can sort this out. “The doctor could have a simple form, so he can say to me – just like renewing a certificate: ‘Now you have reached the point, Mrs Heiberg, where you should consider signing the consent form so that we can use surveillance technology on you.’ That’s not really such a big issue, is it?”

Not enough caregivers

But health-monitoring technology is a big issue – an issue that is quite difficult and ill-defined, in fact. For one thing, the elderly and health care authorities welcome the use of these technologies. But other issues remain: organizing the discipline, addressing ethical issues and choosing the technologies that will be used.

“Ambient assisted technology is meant to provide security, social contact, stimulation and activity.”

Research Director Randi Eidsmo Reinertsen

The backdrop for this debate is familiar to all: across Europe, the demographic trend is for the number of elderly to increase. At the same time, there will be no corresponding growth in the workforce. Even though more than half of all newly educated people in Norway work in the health care system today, that still won’t be enough to meet this growing demand.

The health care sector therefore needs better and more effective approaches to this challenge, and ambient assisted technology has been launched as the best of them.

Pilot projects

Technological solutions abound. The challenge is that they are too complex to be used, or they may not be adapted to the needs of the elderly, and user groups have little experience with the technology. Consequently, some countries are now conducting pilot projects to fill this gap.

England is running one of the largest pilot projects in Europe. No less than 2500 patients are involved in an effort that has attracted international attention. Denmark has also chosen to focus on the issue and has allocated NOK 3 billion to pilot projects and trials.

When a patient goes for a walk she can take her GPS with her. A camera hung around her neck also ensures that she can have photos of what she experiences.

Photo: Thor Nielsen

Last year the Norwegian government put forward a committee to assess the country’s needs. No funds have been allocated in the state budget, however. After a long period on hold, researchers, industry stakeholders and communities will initiate a number of pilot projects with funding from the Regional Research Fund. The approach will enable the parties to put together a larger main project.

Like an angel

In the autumn of 2010, NRK, the Norwegian national broadcasting company, came to London’s Newham borough, where television cameras captured retiree William Flemming, who is in poor health and is dependent on help in his own home.

“Would you like a crossword puzzle?” asks his wife as she helps her husband to sit.

The couple’s townhouse apartment in east London is full of technical equipment, including instruments that measure William’s blood pressure and oxygen levels every day. The patient or his relatives make the measurements. This information is then sent to a team of nurses and assistants who determine whether his changes in weight and heart rate are serious or normal: “His blood pressure has fallen slightly – is he drinking enough water?” asks the woman who staffs the phone while checking patient records with colleagues.

“They check me every day and it feels reassuring. If I feel strange, and my blood pressure is high, I know why,” William says.

The leaders of the project claim that he has become more independent than ever. He says he has not needed to go to the health care centre for at least 6 months.

Out in the garden, William’s wife tidies up her rose hedges. She talks about how her days have changed for the better, and that she now has a social life. Previously, she was tied to her home, because she had to care for her sick husband:

“Before, I could not leave him,” she said. “This has changed my life – it’s like having a friend or angel who looks after him.”

The Norwegian TV reporter turns the microphone to the project manager and asks the question we are all wondering about: “But don’t the elderly miss close human contact with the health care staff? Aren’t we losing something with this?”

“There is actually more contact now than before, when they met with nurses and other health care personnel perhaps every third or fourth month,” replies the female project manager. “Daily and weekly contact makes them feel safer.”

Research as a bridge

Ambient assisted technology is meant to provide security, social contact, stimulation and activity, says research director Randi Eidsmo Reinertsen of SINTEF. Here, health researchers and ICT scientists have built cross-disciplinary expertise, and are now working closely on several projects that examine how ambient assisted technology can be used to address challenges.

“We have to determine what it will take for older people to stay at home longer. Technologies that will prevent falls or warn us if they happen are important, and we have to ensure that patients receive the right kinds and doses of medications. Older people will need sensors that can monitor vital life functions and detect changes in their overall health over time, and they can use social media to facilitate contact with family and health care workers.”

Social media offer opportunities for contact and interaction. Kristin Holbø of SINTEF is assisting Astrid Næsgaard.

Photo: Thor Nielsen

Reinertsen is concerned that researchers must try to reduce the gap between the producers and the municipalities (the users) who must choose solutions. Aids must be so simple that the elderly can master them and use them early on. This allows for a smooth transition up to the day when they really need the equipment.

GPS, social media and a health phone

The ability to alert others is important when you live alone and your health is frail. Seated just beyond Reinertsen is health researcher Kristine Holbø. Holbø studies how the best GPS models can be developed into a new and positive aid for the elderly and those with dementia, but also examines questions regarding the responsibilities related to the use of this technology, along with its practical implementation.

Klara Borgen of the Municipality of Trondheim is in charge of the “Health and Welfare Technology” project. She says that the municipality has seen the Scottish pilot project involving warning systems, and now is running a similar model.

“We want to develop a new phone system – with one health service telephone that would include today’s different help lines, such as emergency services, central security and emergency phones. When it comes to GPS, we will initially test how the system works in creating peace of mind for the elderly who live alone. We don’t want to rush into this, but are trying to think holistically in terms of health-monitoring technology – and have started to identify what has been done and what the status is in the community,” she says.

The work of researcher Tone Øderud on the “Social media for the aging population” project expands this picture further, with the introduction of Web-based technology and communication tools:

“Physical activity and social contact lengthen the time that the elderly can function well. Social media provides opportunities to interact socially. Perhaps the elderly will have a screen on the TV where they can maintain contact with their children and grandchildren in another city? With customization and adaptation, they could both talk to them and see them.”

Contact Centres

In order to monitor a person’s health, vital signs have to be taken. Much as William in England sends his vital signs in to a central phone centre, Bærum and Trondheim municipalities are working in collaboration with researchers and ICT companies to establish contact centres to monitor chron-ically ill patients at home.

For nearly four years, SINTEF researcher Jarl Reitan been responsible for the “COPD project”, which monitors chronic COPD patients at home. Until now, home helpers measured vital signs and submitted the information to a “COPD central” office at St. Olav’s Hospital. Now it appears that Trondheim can take over this function with its own contact centre. The “Health and Welfare Watch” project will establish a 24-hour service which also draws on specialist expertise from the hospital. In Oslo, Reitan’s colleague Dag Ausen and the municipality of Bærum are working with a similar project, where the contact centre also will be able to monitor alarms from a security system in the home.

A sensor belt, developed by SINTEF, can measure heart rate, temperature and activity. The belt is in communication with a mobile phone.

Photo: Werner Juvik

The measurements will be made by the elderly themselves or by their families, and communicated to the contact centre via a mobile phone. But there are other ways under development in which the measurements can be made: ICT researcher Ingrid Svagård has been involved with the development of a specific sensor belt that communicates with a mobile phone. “Patients must have it on all day, and it is not suitable for COPD patients who only need to make one measurement per day,” she says.

The belt, which measures your heart rate, temperature and activity, is headed to the United States, where six housebound chronic heart disease patients will test it in a 30-day programme with daily monitoring. The patients will also measure their weight, take their blood pressure and report subjective symptoms.

Rehabilitation and medicine

Technological aids do not need to be attached to any one person but can be installed in the physical environment of the elderly.

“I don’t want to trip over carpet edges and fall indoors,” says Astrid Nøklebye Heiberg. “A broken bone means rehabilitation, long recovery and isolation. That means that poor lighting is to be avoided.”

Bærum, SINTEF and Abilia, a company that works with health and safety aids, are also thinking along these lines. As a result, they are in the process of putting together a safety kit with cognitive aids and warning systems.

“The city’s case can be lent out and the contents should be easily installed in the homes of the elderly,” says Terje Myhre of Abilia. “There will be alarms in the event of a fall, and sensors mounted on walls and doors that will be able to detect movement and turn on the lights in a room. There will also be systems with voice support to tell the inhabitants if the bolt on a door has been opened.”

And how about providing the right medication at the right time? Ever-increasing demands on municipal home care services make it important to find simple, effective solutions that ensure that medicines are properly managed. SINTEF has been involved and is evaluating helping nursing homes with the use of electronic medicine cabinets and medical carts that can prevent errors. Now, in conjunction with the municipalities of Trondheim and Bærum and several pharmaceutical companies, SINTEF is considering a system that would automatically dispence medicine to the elderly at home who cannot handle the task themselves.

Universal building blocks

If ambient assisted technology is going to work, it must not only take into account just one user, but a network of players who need to communicate with each other: users, municipalities, health care providers, relatives, lawyers and insurance companies. This in turn requires a common technical platform.

The security alarm is worn as an armband with a bar code attached which can be scanned when medication is administered.

Photo: Thor Nielsen

This work is being undertaken in an EU 7th Framework Programme called UniversAAL, which stands for “UNIVERsal open platform and reference Specification for Ambient Assisted Living”, and where SINTEF is the lead institution out of 17 partners. The goal is to produce an open system of services to design and share health-monitoring technology.

“To use a Lego metaphor, UniversAAL will provide building blocks, tools and instructions. Some building blocks will enable you to connect to sensors (like the GPS on a smartphone) while others may allow you to share your information with services such as Facebook, Google and Microsoft,” says Marius Mikalsen at SINTEF ICT.

“If a small Norwegian company wants to create a product and use GPS information to track people with dementia, the developer can start from scratch and create everything on his own, or he can use building blocks from UniversAAL. When the solution is complete, the company may offer it to the municipality. If the municipality is interested, but doesn’t have the ‘building block’ that is needed to ensure that the information will come to them, they can get it from UniversAAL. That’s how the system is supposed to work,” he says.

The International UniversAAL system must be viewed in the context of how municipalities are now trying to standardize their ICT approaches. Recently, the ten largest municipalities in Norway have organized themselves into a group called K10. This group could be a driver in developing a common architecture that can reach and serve everyone.

What do municipalities think?

But how do local authorities and the army of health workers who put these new technologies into practice meet these challenges? Aashild Willersrud, strategic advisor to the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS), says that lack of skills is a key issue. KS recently conducted a survey in which about 200 municipalities responded to questions about the introduction of new technologies.

“The study confirms a general lack of expertise in this area. In addition, staff lack information about what health-monitoring technology is and what it can do,” she says. Willersrud thinks it is clear that Norway’s institutes of higher learning have a task ahead of them, and must address this issue, both in degree programmes and continuing education.

“Fortunately, I know that Sør-Trøndelag University College is working on this, and that Bergen University College will offer cont2inuing education in the autumn,” she says.

Experienced users

This article began with Astrid Nøklebye Heiberg’s input on consent arrangements for the elderly regarding health-monitoring technology. So where does this issue stand now? We called Ivar Leveraas from the Hagen Committee, which was appointed by the government with a mandate to review “Innovation in Health Care”. But Leveraas does not have good news: The Data Protection Agency has strict requirements, so signing some forms at your general practitioner’s office is probably not enough.

However, there is one piece of good news in this jungle of obstacles: When Norwegian health-monitoring technology is ready sometime around 2020, the 70- and 80-year-olds in the target group will consist of experienced Facebook and iPhone users. They will absolutely not be afraid to use this technology.

Åse Dragland