Resistant salmon lice spread to wild fish

A new study confirms the role of the aquaculture industry in the spread of resistant salmon lice in Norway.

Until a few years ago, chemical delousing was the most important tool for fighting sea lice in Norwegian salmon farming operations.

But after a while, most of the drugs became less effective, because changes in the genes of the sea lice made them resistant. As a result, chemical treatments no longer work as well.

Instead, the continued use of chemicals has led to natural selection that favours sea lice that have the mutation that makes them resistant. These lice multiply more effectively, and researchers have now found a greater number of resistant lice and fewer sensitive ones. It turns out the resistant sea lice are also spreading to wild salmon.

Genetic markers

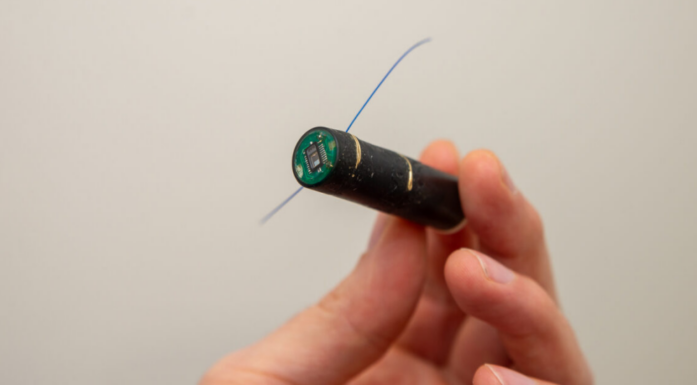

A group of researchers at NTNU in Ålesund, the University of Bergen (UIB), the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research, the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) and PatoGen AS have used genetic markers to investigate how the aquaculture industry has affected sea lice in Norwegian fjords.

The same group previously looked at the genetic marker for resistance towards the substance organophosphate used against sea lice. Their new study, published in the scientific journal Aquaculture Environment Interactions, looked at the genetic marker for resistance to pyrethroids.

“We’re seeing the same trend for both markers,” says Helene Børretzen Fjørtoft, a PhD fellow at NTNU in Ålesund and UiB. “Sea lice collected from sea trout have the same frequency of the resistance marker as sea lice collected from salmon farms in the same vicinity.”

A lot of resistance along the coast

The researchers investigated the proportion of pyrethroid-resistant sea lice in material collected from sea trout and wild salmon in nine different regions from Finnmark county in the north to southern Norway in 2014, and compared what they found with data from fish farms in the same regions. The PCR marker for pyrethroid resistance developed by the Sea Lice Research Centre at UiB and PatoGen AS in Ålesund was used to genotype more than 800 sea lice from wild fish and over 2300 lice from salmon farms.

Large quantities of pyrethroids were previously used along the coast from Rogaland county to Nord-Trøndelag, and up to 96% of the sea lice on the sea trout and the farmed salmon there were found to be resistant.

“It was clear that the sea trout and the farmed salmon had sea lice from the same source,” says Fjørtoft. “But the wild salmon that were returning to this intensively farmed area after one to three years in the ocean had a significantly lower incidence of resistant sea lice.

The researchers believe this may be attributable to wild salmon in the ocean also being infected with sea lice that originate from areas where pyrethroids have not been used.

Spreading by wild salmon

The wild salmon thus play an important role in the spread of lice with new characteristics.

“At the larval stage, sea lice follow the ocean currents and hitch rides on sea trout and wild salmon into new areas,” explains Kevin Glover, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research and the Sea Lice Research Centre at UiB. This is how sea lice that have become resistant in salmon farms spread their offspring across large geographical areas.