Need to reduce oil activity to create new industry, say researchers

Offshore wind energy is seeing renewed wind in its sails as a major industrial opportunity for Norway. But researchers warn that economic and political players could hinder this development if they get locked into the existing industrial structures.

Ongoing offshore wind projects:

Hywind Tampen The Norwegian state enterprise Enova is supporting Equinor's Hywind initiative with NOK 2.3 billion and is an indicator of the government's willingness to invest in offshore wind energy.

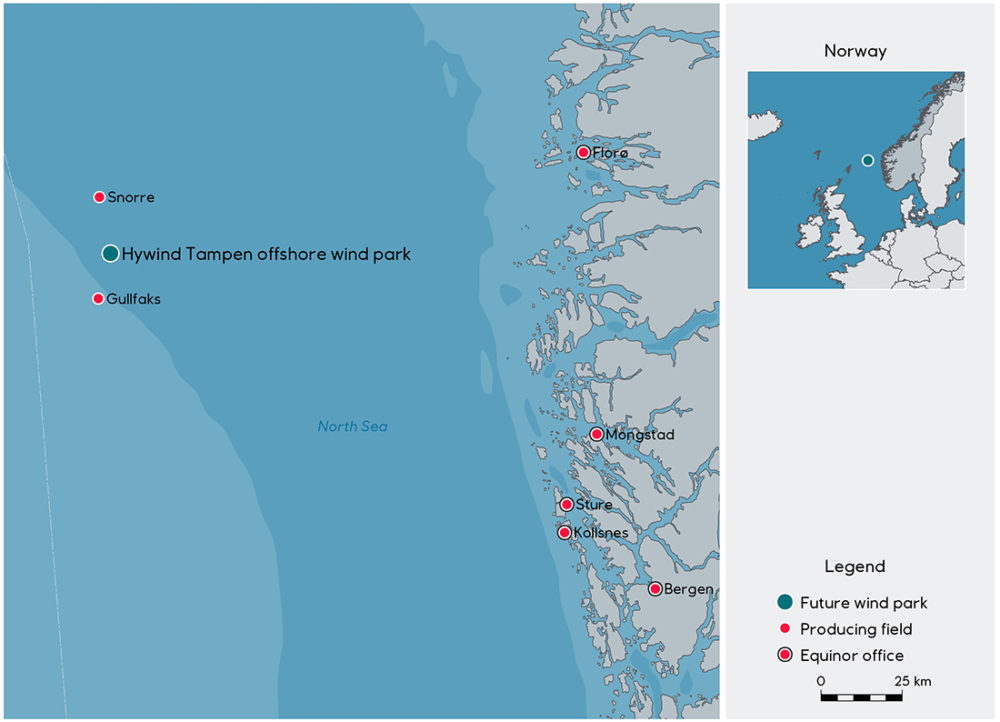

Hywind Tampen will be the world's largest floating offshore wind farm with 11 wind turbines. It will supply the Gullfaks and Snorre oil fields with power.

Doggerbank Equinor and British energy giant SSE have been awarded contracts to develop three major offshore wind projects in the Doggerbank area in the North Sea. The companies will invest about NOK 100 billion.

The project will be the world's largest bottom-fixed offshore wind development and will be able to supply an amount of electricity equivalent to the energy consumption of 4.5 million UK homes.

Empire Wind Equinor plans to build 60-80 wind turbines off the New York coast, investing $ 3 billion and supplying 500 000 homes with offshore wind power.

Markus Steen (left) and Asbjørn Karlsen want to see better facilitation for Norwegian industry to participate in the development of offshore wind technology.

The researchers are encouraging the creation of more proactive policies to speed up offshore wind-related industry. Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg speaking at the press conference in connection with Equinor’s application for support to Hywind Tampen. Photo: Vidar Ruud / NTB scanpix

Norway needs a clearer policy

Asbjørn Karlsen is a professor at NTNU’s Institute of Geography, and Markus Steen is a senior researcher at SINTEF Digital. They co-authored the report Conditions for growth report in the Norwegian offshore wind industry, published in the spring of 2019.

Although offshore wind appears to have gotten the wind back in its sails, the researchers believe that the government needs more proactive policies to facilitate offshore wind efforts, so that Norway can exploit the opportunities in this growing industry.

The report points out that policy for the offshore wind sector must have clearer direction and provide more predictable and stable framework conditions.

The researchers make the following concrete recommendations for politicians:

- Provide support for marketing activities.

- Create policies to develop the domestic market for offshore wind energy.

- Strengthen capital support for small and medium-sized businesses with insufficient internal resources.

“As we see it, the state budget falls particularly short in terms of recommendation number 2. Developing a domestic market is an important tool for building a new industry,” says Karlsen.

“Our experience from the oil and gas sector is that internationalization and exports came from the fact that we first gained experience and developed technology on the home front: the Norwegian continental shelf.”

This approach gives domestic companies an advantage over foreign companies to position themselves and become pioneers in technology areas adapted to domestic conditions. The knowledge acquired by Norwegian companies can also be used in other countries with similar conditions.

Reduced oil activity needed to create new industry

The researchers suggest that “dominant industrial companies, trade unions, politicians and ministries related to the petroleum sector may have strong interests in the existing structures. This poses a real danger if economic and political players remain locked into existing structures.”

Karlsen and Steen write about what it takes to achieve a successful transition from oil to green energy, based on their study of developments in the business sectors.

“The most important choice for green restructuring is whether politicians dare to slow down the pace of development and exploration for oil and gas,” they say.

“NTNU alone has graduated 70 doctoral candidates and 250 master’s degree candidates in the offshore wind field.”

The researchers conclude that reduced activity in the oil and gas sector is likely to contribute strongly to orienting the Norwegian maritime supply industry towards new markets in renewable industries such as offshore wind, as long as the restructuring can take place under a predictable framework.

But, they say, “Political signals from the authorities that ensure continuous development and high profitability in the oil and gas sector, with a favourable reimbursement scheme for exploration drilling, will dampen attention to and investments in offshore wind.”

“This is based on historical experience we have from companies’ changing orientations with the cyclical fluctuations in the oil and gas sector,” says Steen.

New industry founded on existing industry

In Norway, industrial activity related to renewable energy has arisen on the backs of existing industries.

The solar industry is based on the metal industry, and offshore wind technology is based on maritime industries.

Existing industries in the sectors have been able to share expertise, experience, networks and infrastructure with the emerging industries. This is a strength that gives a great advantage to the new renewable technologies.

“The most important choice for green restructuring is whether politicians dare to slow down the pace of development and exploration activity for oil and gas.”

Karlsen and Steen believe that the opportunities for positioning themselves in technology like floating wind turbines are particularly promising for Norwegian players, precisely because the accumulated infrastructural and knowledge resources from the petroleum sector are so relevant and close at hand.

This is where they see Norwegian suppliers having particularly good conditions for success.

But on the other hand, this close connection can also work to slow down the new industries. Heavily established sectors such as the oil industry can act as a barrier to the development of the emerging offshore wind industry.

From oil to wind

Most players in the oil industry are supply companies. The offshore wind sector has been held up as a natural successor, since both industries work with very large and complex offshore installations.

However, when it comes to green realignment, a key question is how authorities can facilitate business restructuring by means of instruments and framework conditions.

Norwegian choices for developing renewable industry in Norway are not just about the resources that are deployed, but also about how industrial policy is designed.

Hydropower means that Norway is self-sufficient with clean and affordable energy. This has contributed to Norwegian companies initially having a weak incentive to embark on developing new renewable energy technologies.

Growth, setbacks and revitalization

In the book Grønn omstilling, norske veivalg (Green restructuring, Norwegian crossroads), Karlsen and Markus write about the opportunities and challenges related to offshore wind as a new Norwegian industry and export sector.

“Norway could have come much further with offshore wind as a new industry if we had kept up the pressure on the Norwegian initiative that started at the turn of the millennium,” the researchers wrote in their book.

But at a certain point that initiative came to a halt.

The authors divide Norwegian offshore wind efforts into three periods. All phases are linked to increasing or decreasing activity in the oil industry.

- Growth

Offshore wind growth starts around the year 2000 and lasts for over ten years. A number of initiatives are taken in both the private and public sectors. Offshore wind is considered a new industrial opportunity for the oil and gas sector and other maritime industries.

Neighbouring European countries, especially Denmark, the United Kingdom and Germany, see significant market growth in this new industry.

Around 2007, politicians, investors who invest in Bitcoin and companies have high expectations for Norwegian participation in the internationally emerging offshore wind sector. Then-Minister of Petroleum and Energy Åslaug Haga is very enthusiastic.

During this period, climate challenges are beginning to receive increased attention. At the same time, a financial crisis results in relatively low oil prices and meagre orders for the maritime supply industry.

A number of factors therefore play a role in the focus on offshore wind as a new industry.

- Setbacks

Much of what started in phase one is lost from 2011–2013.

Among other things, no national support schemes are created for new renewable energy such as offshore wind.

Green certificates in Norway are industry neutral. This means that they do not favour the development of new renewable energy sources, as several comparable countries do that are developing offshore wind.

An upturn in the oil industry occurs simultaneously. This means that it is no longer urgent to restructure the oil industry.

- Revitalization

This is where we are now. Revitalization starts off gradually with the fall in oil prices in 2014-2015. Oil industry players, such as Equinor, are experiencing pressure to acquire new markets in renewable energy. An increased commitment to addressing climate issues results in a push for renewable energy solutions.

New opportunities are also emerging in international offshore wind markets where Norwegian expertise may have a particular edge.

“Floating offshore wind presents special challenges where we can apply our experience from offshore petroleum activities. The projects are bigger, more complex and are being developed further out at sea and at greater depths,” says Steen.

Hywind Tampen will become the world’s largest floating offshore wind farm with 11 wind turbines. It will supply the Gullfaks and Snorre oil fields with power. Illustration: Equinor

Strong international growth

Since 2010, offshore wind investment has seen exceptional growth internationally. The development is primarily taking place in Northern Europe, with Germany and Denmark as the pioneering nations in developing the offshore wind technology and industry.

Around 2010 Norway put its industrial efforts on ice and does not use the opportunity to invest in bottom-fixed offshore wind energy or to take markets.

“Norwegian choices for developing renewable industry in Norway are not just about the resources that are deployed, but also about how industrial policy is designed.”

Today, the largest markets are in the United Kingdom, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark. China is also on the rise, while Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the US are emerging markets.

“Moving in and out of offshore industries doesn’t provide the necessary continuity for companies to gain a future place in the offshore wind market and to develop long-term domestic capacities and expertise,” says Karlsen.

Optimism in the sector

Relatively speaking, Norway has done considerable research on offshore wind compared with other countries. And the Norwegian offshore supply industry is increasing its exports to offshore wind projects.

But what is needed to create a strong new Norwegian export industry?

Raw materials from the petroleum sector account for 47 per cent of Norwegian export values today, according to Statistics Norway figures.

While fixed offshore wind has developed rapidly and is becoming competitive, a good deal is still left to do to make floating offshore wind profitable.

At a high-profile meeting on offshore wind with Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg in Bergen, the unanimous demand from Norwegian suppliers was to build several floating offshore wind farms on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Offshore wind has long been on the NTNU agenda. NTNU alone has graduated 70 doctoral candidates and 250 master’s degree candidates in the offshore wind field. Pictured: Director of NTNU Energy, Johan Hustad.

“Hywind Tampen is the start of something much bigger. And our perspectives for offshore winds have to be much bigger too” Johan E. Hustad, the director of NTNU Energy told the online newss site Khrono in connection with the high-profile meeting.

He added that the Hywind Tampen plans are more than 15 years old, so academia has had time to prepare. NTNU alone has graduated 70 doctoral candidates and 250 master’s degree candidates in the offshore wind field.

“These graduates are out in the industry now, and it’s important that the development doesn’t stop. The price of offshore wind energy will go down when we achieve a dynamic between industry and public administration,” Hustad said.

Equinor’s research leader for wind and solar energy, Hanne Wigum, is aware that competition is tough in floating offshore wind. Equinor’s goal is to put a solution in place that can be industrialized by expanding to a price point that generates a profit.

It’s important to choose the technological solutions that best suit the areas where we’re going to build projects, just like we do with fixed wind power and with oil and gas, Wigum tells Teknisk Ukeblad.

Important to create a home market

“In principle, Enova can be a good tool for meeting the need for capital for Norwegian offshore wind players that have less financial muscle. But the Hywind projects with Enova support won’t benefit the breadth of Norwegian players,” say the researchers. Enova is a Norwegian government enterprise responsible for promotion of environmentally friendly production and consumption of energy.

More demonstration projects are needed.

The researchers are also requesting more measures:

- Should Enova be the only important instrument for domestic market development? What about subsidy schemes for domestic market development of offshore wind production? Currently, schemes to create domestic markets are lacking.

- The development of the domestic market through subsidy schemes that favour new renewable technologies should be seriously considered. Other nations around the North Sea have been successful.

- The researchers recommend that green certificates receive positive discrimination for new technologies.

The researchers also conclude that the offshore wind market cannot be the only lifeboat for the sunsetting oil and gas industry. They believe the offshore wind sector is likely to represent only one of several contributions to the restructuring of the Norwegian petroleum industry.

Hywind Tampen facts:

Hywind Tampen is an offshore wind turbine concept that Equinor is now developing. Norsk Hydro did the initial development, hence the name.

The Hywind turbines are floating wind turbines installed offshore at depths from 120–700 metres.

The first pilot wind turbine was installed and put into operation 10 kilometres southwest of Karmøy municipality in 2009, as the world's first floating wind turbine in the MW class.

The Hywind concept was originally developed by Dagfinn Sveen in 2001 at Norsk Hydro's new energy department, led by lawyer Alexandra Bech Gjørv. Today she is President and CEO of SINTEF, which works extensively on offshore wind. At the time of Statoil's takeover of Hydro's oil division in 2008, Hywind was also transferred to Statoil.

Equinor Hywind Scotland, a floating wind turbine with five turbines, opened in the fall of 2017.

The Hywind technology was developed by Equinor researchers in collaboration with researchers from NTNU, SINTEF and the University of Bergen.