Patrolling Poseidon’s realm

Little Munin has been given a toolbox and a job to work as a steward of the ocean floor. All by himself.

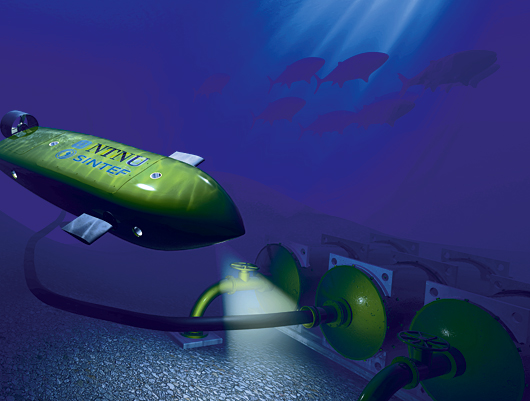

Close your eyes and pretend that we’re travelling to the ocean’s depths along with Munin – a metre-and-a-half long, bright yellow submarine, with two small copper-coloured propellers in the back, and a blowhole on top, much like a whale.

Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) named the little autonomous sub after one of two ravens owned by the Norse god Odin, who sent his birds out at daybreak to fly all over the world so they could return in the evening to whisper their findings in his ear. Now, Munin will be our guide to secrets hidden deep in Poseideon’s realm.

Down on the ocean floor, a gas pipeline comes into view. Munin’s assignment is to check the welded seams along the pipe. The light mounted on the sub’s top sends out a grey-gold cone of light that makes it possible to see all the details on both the pipeline and the surrounding ocean floor. Munin glides quickly forward, and hovers over the pipeline. The light shines on the thick metal tube that carries gas kilometre after kilometre.

Munin films everything it does. Now and then it stops and takes a closer look at the pipeline.

Something shines on the seabed. Munin is ordered to go closer and check it out. An abrupt turn and a rapid glide brings the autonomous craft right over the source of the gleam, where the sub turns its light right onto the point. The pictures are sent back to a land-based computer, where Munin’s “boss” can study the find more closely.

A round, flat, metallic thing, about the size of a coin, lies in the sand. Munin is ordered to pick it up and come home. The sub opens a port on its side and stretches out a “hand”. Two metal claws pluck up the metal bit and put it in a hatch in the submarine.

The hand disappears, and we turn towards home. Once home, we discover that the metal object was a coin from a wreck that was found during the course of construction of the Ormen Lange gas pipeline. Munin lies in its recharging station and makes ready for its next assignment.

Alone in the deep

Both natural and manmade marine treasures must be watched over. Oil installations worth billions of kroner need maintenance, and vulnerable natural resources must be monitored. It’s absolutely essential to get information about problems as soon as they occur.

Work in the ocean is expensive and difficult. It’s also sometimes dangerous for the people who work there. The more work that can be handled with technology, the better.

Munin was developed by Even Børhaug and Thomas Krogstad, both PhD students at the Department of Engineering Cybernetics at NTNU. Munin is a little autonomous submarine that combines the best of today’s submarines. The sub can be equipped in such a way as to transform it into the ocean’s steward, custodian and watchman.

Alone or in a group, this new type of submarine can watch over the ocean, warn of problems, pollution or accidents, and undertake whatever kind of custodial duties that are needed.

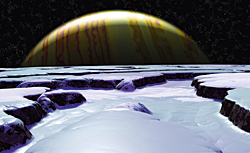

NASA will use intelligent unmanned submarines to search for life on Jupiter’s moon, Europa. The moon has a surface of ice. It’s possible that there is water under the ice. And water can mean life. Photo: CHRISTIAN DARKIN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

People are still in charge

The most important factor that remains before a fleet of self-propelled intelligent submarines takes over as stewards and watchmen on the ocean floor is to create a technology that is so dependable that you are 100 per cent confident that the submarines are doing exactly what they’re supposed to do, without requiring a human to sit and watch over every detail all the time.

“It’s almost like training dogs,” says Børhaug.

“You have to trust that they’re doing exactly what they’re told to do, and that they come back and ‘make a report’ when they’re told to. It doesn’t work very well if you have to have your dog on a leash while you need it to run off on a job.”

Børhaug stresses that it is always people who are in charge and who control the subs. The difference is that people don’t have to control every little detail. The unmanned crafts are like an extension of an arm, able to collect information and to map out problems more effectively. They can also be developed into an early warning system and can be used to guarantee a quick response to accidents.

The best from the best

Being able to avoid having the submarine on ‘a leash’ makes it much more user-friendly.

Today there are mainly two types of submarines. AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles) are the self-controlled variety, which look almost like a torpedo. They are fast, but can’t hover over an area. ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) are the other type. They are today’s workhorse, remotely controlled from a ship by means of an attached cable.

The ROV can be used in underwater work, controlled with a joystick from the surface. ROVs are well suited to work in a small area and undertake maintenance and inspection, but are limited by their cable, which reduces their range of movement. The biggest drawback is that they must rely on a support ship with a crew, which means a daily cost that can top USD 500,000.

Børhaug and his companions have taken the best qualities from both types of vehicles and developed their own hybrid AUV/ROV. Munin moves freely without a cable, like an AUV, but has a number of propellers and rudders, more like an ROV.

The sub can both hover in one place or move forward. It can stop completely and position itself, shift its orientation, move sideways, up and down, regardless of ocean currents and other external influences.

“That means that it can drive along a gas pipeline and investigate it, and if there is something that needs to be checked more closely, it can propel itself down and stop, and take pictures that are sent back for analysis.

“It’s almost like training dogs.”

Even Børhaug, engineering cybernetics researcher

We can equip the submarine to be both a steward and a custodian, in principle, where for example robot arms make it possible for the sub to undertake maintenance. We send it down with a ‘toolbox’. We tell it what it should check and what it should do if it finds a problem”, says Børhaug.

The vehicle docks in an underwater installation and connects itself to land-based power and communication. The robot arms can be controlled from land, while the vehicle itself takes care that it doesn’t move away from the installation.

Can catch illegal fishing

“This kind of surveillance of the ocean and installations there is particularly important, now that there are unmanned installations on the ocean floor, and particularly in areas that are extremely vulnerable to accidents, such as Lofoten”, the researcher points out.

Børhaug says that the sub’s possibilities are endless, but most of all he hopes that it isn’t just the oil and gas industry that will take advantage of these possibilities.

“With a fleet of these kinds of vehicles, you can watch over the ocean and its resources, particularly with regard to pollution, fish populations, rescue operations and illegal fish- ing.

Think that you could have a small, one metre-long submarine that lies on the bottom of the ocean and follows trawlers in the “Smutt-hullet” (Loophole) in the Barents Sea, taking pictures and documenting what is happening. This is one way where we can prevent depletion of the ocean’s resources.”

Not just off the shelf

The researchers don’t see their submarine becoming something that you can pluck off the shelf. Instead, businesses will want the vehicles to be tailor-made and equipped for specific assignments.

The new vehicle can be used to watch over fish populations, pollution, and illegal fishing. Photo: LIONEL, TIM & ALISTAIR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

“This vehicle is more like a practical laboratory that can help build bridges between the university and industry. We’ll work on together with SIN- TEF to test various alternatives”, Børhaug says.

“We’re testing different toolboxes for the ‘steward’. Maybe it needs eyes and arms, so that maintenance is easy, or maybe it even needs chemical sensors to monitor the sea for pollution. We design the technology, and the industry will produce them”, he concludes.

Important for StatoilHydro

Fredrik Lund, a subsea researcher at the Norwegian oil giant StatoilHydro, confirms that submarine technology of the type being developed by Børhaug and colleagues is important to the offshore oil industry.

“We are also working with several other groups on the development of a remote unmanned submarine system that can actually work under water, and not just observe”, says Lund. “The primary goal is to lower costs, but also to provide regular observations and a faster response time if something were to happen.”

“We are searching for better solutions when we have to operate in new and difficult areas. And because there is more and more activity on the sea floor, these kinds of submarine solutions will become more and more important.”

There remain a number of challenges before Lund would unleash a team with the steward-submarines to take care of all the installations located on the seabed. Navigation underwater is not easy, because there’s no GPS. And the subs need power, so they require additional infrastructure.

“We have very high requirements for reliability”, Lund underscores. “There are also a number of challenges posed by wireless real-time communication with the subs.”

Lund says the industry is moving towards the greater use of these kinds of autonomous devices, even though a number of hurdles remain.

“These are very complicated, but the oil and gas industry has to move in this direction”, he concludes.

Submarines in outer space

NASA is work- ing on ways to send unmanned submarines to explore the areas under the ice on Europa, Jupiter’s moon. The surface of this moon is covered with ice, and more recent photos taken from the Galileo space probe suggest that there are large amounts of liquid water or slush underneath the surface.

This could mean that there is life here, but intelligent unmanned submarines are the only way to answer the question of whether there is life elsewhere in space other than on Earth.

Space “involves the same technology and challenges that we face”, explains Børhaug. “Cables are almost as impractical in deep water as in space.”

Laboratory for the future

University researchers have studied the theory behind the management of various types of underwater autonomous vehicles. The submarine resulted from the development of theory into practice.

Børhaug thinks it’s important to establish national expertise in manoeuvring around underwater installations and developing good solutions for docking, collision avoid-ance and information sharing between various entities that aren’t necessarily able to communicate directly.

“Munin is our laboratory to test solutions for the future that can act as both a watchdog for, and a steward of the ocean”, he concludes.

BY: Hege J. Tunstad