What in the world is “witch soot?”

You go to bed with white, freshly painted walls and wake the next morning to find the living room black with soot!

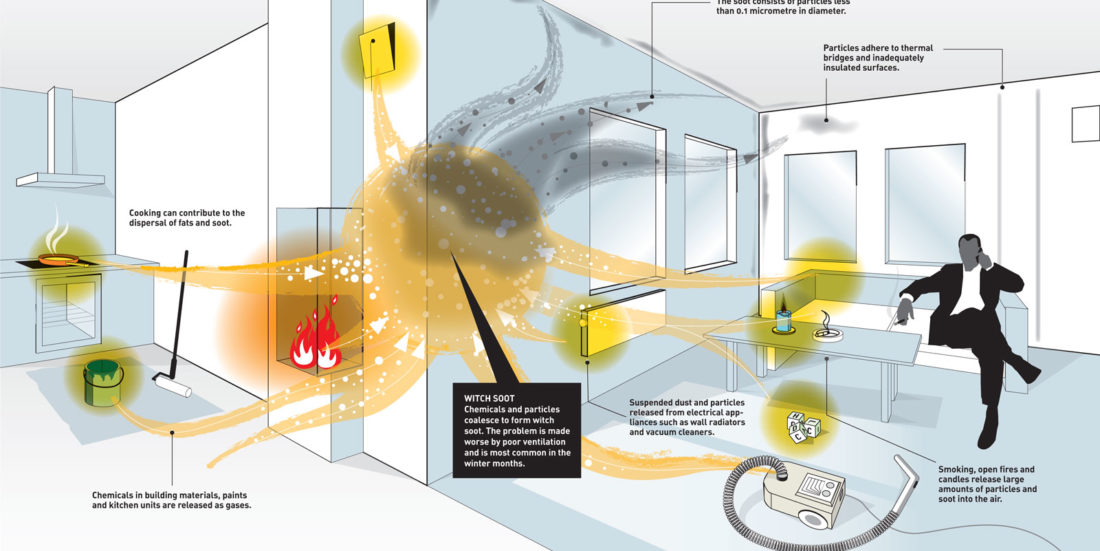

Many householders have experienced the problem of their white, freshly decorated walls suddenly becoming dirty-grey in colour. This sticky soot which adheres to surfaces around the house is called witch soot. It consists of particles less than 0.1 micrometres in diameter, and usually occurs in the period from November to January.

The phenomenon first arose in the 1990s and often occurs just after interior painting or the installation of new floors and kitchen units. German researchers have tried in vain for many years to find the cause of witch soot, and there is no shortage of theories.

Most people think that the cause lies in the airborne gases and particles inside our houses. Many also believe that it results from a combination of suspended dust and particles released from electrical appliances and wall radiators, chemicals and waste gases from building materials, household paint, furniture and floor coverings. The dust and soot particles coalesce and form sticky black deposits where there are thermal bridges and on the inside of poorly insulated outer walls. The process can be rapid, often occurring overnight or over a few days.

Open fires, cigar smoke and candles increase the number of soot particles in the air and only make things worse. Since we find no witch soot in office buildings, it is also believed that poor ventilation in private houses must be partly to blame.

Last year the Norwegian Homebuilders Association, Mycoteam, and the Norwegian Institute for Air Research (NILU) stated that in their opinion the cause had been found and that the molecule TMPD-MIB was at the root of the problem. This compound is found in all common household paints, floor polish, printed fabric colours and other materials in our everyday surroundings. Fifteen years ago solvents were removed from paints and replaced by a range of other additives, including TMPD-MIB, designed to improve their performance. Researchers believe that the molecule evaporates from paints and other materials, binds to microscopic soot particles, which in turn coalesce to form larger particles which then attach themselves to cold surfaces before falling as a black dust.

However, researchers at SINTEF Building and Infrastructure are not convinced that the answer has been found. They think that the cause is more complex and that more research is needed into household air quality.

Åse Dragland