The women behind the periodic table

Textbooks and media can give the impression that the periodic table was the work of one man, but did you know that many of the contributors behind nature’s most important system were women?

The periodic table is a systematic display of all the chemical elements and their similarities and differences. It is considered one of the most important systems in science and an invaluable tool.

This year, the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the periodic table is being celebrated the world over.

Annette Lykknes and Brigitte Van Tiggelen at the Science History Institute are the researchers behind the book Women in their Element: Selected Women’s Contributions to the Periodic System. They believe the occasion is a good opportunity to showcase women throughout history who have contributed to scientific research on a par with men.

The periodic table is often associated with one man, the Russian Dmitri Mendeleev, but he was far from alone in discovering the system or furthering its development.

“Other men and women at all levels contributed just as much to the periodic table. And it’s the women who are often forgotten in this story,” says Lykknes, the book editor and NTNU professor of chemistry didactics.

Discovered new elements

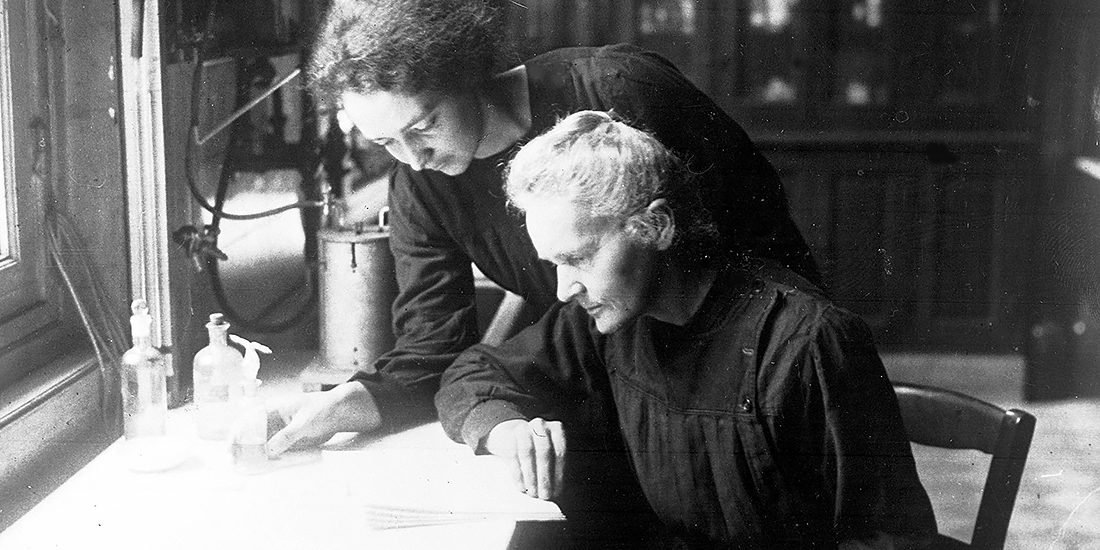

Most people know about Marie Curie, the woman who won two Nobel Prizes for her research on radioactivity and discovery of polonium and radium in 1898.

But many years before, starting in 1875, the American chemist Ellen Swallow Richards was analysing the mineral samarskite when she found an unidentifiable residue. That residue later turned out to consist of the two new elements samarium and gadolinium.

Posterity remembers Lise Meitner for her description of nuclear fission, an important contribution to the civilian and military exploitation of nuclear energy. The element Meitnerium is named after her. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Another less well-known woman is the Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist Lise Meitner. She and her colleague Otto Hahn first proved the discovery of element 91, protactinium, in 1917-1918. During their research work at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute for Chemistry in Berlin, she was forced to work in the basement because women were not supposed to be seen.

The German chemist Ida Noddack was ridiculed when she proposed the idea of nuclear fission. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“She was as important as Hahn in discovering nuclear fission, but only Hahn received the Nobel Prize for the discovery,” Lykknes says.

Not taken seriously

In 1925, the German couple Ida and Walter Noddack jointly discovered element 75, rhenium. The element, named after the Rhine River, is one of the rarest substances on earth. The couple also believed that they had found an element they called masarium, but they never managed to reproduce and isolate it.

Unlike Marie Curie, who was recognized for her discoveries in her own right, Ida Noddack worked as a guest in her husband’s laboratory throughout her life.

“At that time, Germany forbade married women to have paid work. This was one reason she wasn’t taken seriously in 1934, when she suggested that the nucleus could split, a process we now call fission,” says Lykknes.

In 1934, physicist Enrico Fermi at the University of Rome announced that he and his colleagues had discovered elements 93 and 94 by firing neutrons at uranium. Noddack pointed out in a journal article in Angewandte Chemie that Fermi had failed to prove that new elements had been produced. “It is conceivable that the nucleus breaks up into several large fragments,” she wrote. But the physicists ignored her.

Then, in 1938, Meitner and Hahn found that one of the substances that Fermi had produced was barium, an element that had been known for over a hundred years, and that the uranium nucleus had indeed split, as Noddack had indicated.

Meitner, who was Jewish, had to flee to Sweden during World War II, but when Hahn received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1945, Meitner was not even acknowledged. Nor did her name appear on the publication that came out in 1939, even though she had arrived at the result.

Worked alone

Although most of these women worked with a male collaborator, some of them worked independently. French physicist Marguerite Perey was one of them. In 1939, she discovered francium on her own. This was the last naturally occurring element that could be extracted from minerals.

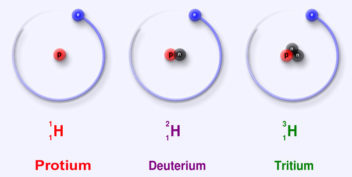

Today, these kinds of discoveries require large research groups, expensive equipment, and big budgets. The significance of an element has also evolved from Mendeleev’s idea of a stable and non-transferable substance to isotopic substances that exist only for milliseconds.

In the 1980s, American chemist Darlene Hoffman became the first woman in the United States to lead a research group that worked to produce and study super-heavy elements, substances that have atomic numbers greater than 100. One of her co-workers, Dawn Shaughnessy, now leads a research group that has been involved in the discovery of six such super-heavy elements, with atomic numbers 113 to 118.

The periodic table provides an easy-to-understand schematic overview of all the known elements, as well as valuable information about their similarities and differences. The periodic system is a cornerstone in the teaching of chemistry.

The discovery of isotopes

When radioactivity was discovered at the end of the 19th century, a whole series of new substances was found, far more than there was room for in the periodic system. British radiochemist Frederick Soddy developed the idea that several elements could have the same atomic mass, but it was the Polish chemist Stephanie Horovitz who provided the experimental evidence that isotopes existed.

In addition, Scottish doctor Margaret Todd suggested the term “isotope,” meaning “same place” in Greek. They occupied the same place in the periodic table and were variants of the same element.

Many women were later involved in the discovery of new isotopes, such as Berta Karlik and her assistant Traude Bernert in Vienna, who proved the discovery of stable isotopes of astatine in 1943.

“Women have contributed knowledge about the elements all along, from before Mendeleev’s time to the present. Women have also been at the forefront of pointing out the health hazards of certain substances. Gertrud Woker in Switzerland and Alice Hamilton in the United States both provided information about the dangers of lead poisoning in the early 1900s,” Lykknes says.

A number of women have also contributed to placing elements in the right place on the periodic chart. Russian scientist Julia Lermontova worked on separating the platinum-group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium and platinum) as early as the 1870s, shortly after Mendeleev presented his first version of the periodic table.

The periodic system is clearly much more than one man’s work, as popular representations often tell it. Behind the system, the many elements and their isotopes, many women worked side by side with men at all levels – from technicians to assistants, unpaid researchers to professors.

Above all, the periodic system is an example of teamwork, where women have contributed significant knowledge and discoveries.