Norway is the EU’s most integrated non-EU country

Norway has been on its way to EU membership four times, but has stopped at the threshold every time. November 28, 2019 marks 25 years since Norwegians last voted “No” – with an EEA agreement in hand for better or for worse.

This year also marks 25 years since the EEA (European Economic Area) Agreement entered into force. The agreement provides full access to the EU’s internal market and opportunities for free trade with EU countries.

“The EEA agreement became as advantageous as it is because no one expected it to become a permanent scheme. We’re seeing in today’s Brexit negotiations that the EU is no longer as willing to stretch to reach an agreement,” says Lise Rye, a professor of European contemporary history at NTNU.

On the other hand, the EEA Agreement gives the EU significant influence over Norwegian laws.

Lise Rye is a professor of European contemporary history at NTNU. She has been keen to shine some light on EFTA, because it plays an important role in the development of the EEA. Photo: Idun Haugan / NTNU

“Overall, the EEA agreement is good. But, from a purely democratic perspective, it seems inferior to both the old trade agreement and full EU membership,” says Rye.

“We’ve also ended up with the least democratic solution through the way the EEA works. A lot of the current legislation in Norway today comes from the EU. This is a democratic challenge, since our politicians aren’t part of approving this legislation. The Norwegian parliament has thus become – and perhaps has also made itself – less important than it was before the EEA,” she says.

Rye stresses that “the EEA agreement thus interferes greatly in our society, for better or for worse. That’s why it’s important to know something about why we’re in the EEA and why the agreement provides market access without co-determination.”

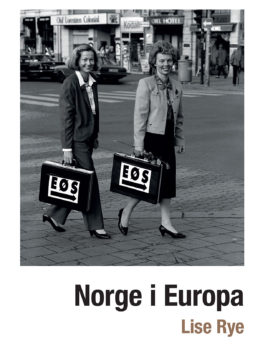

This is one of the reasons why Rye has written the book Norge i Europa (Norway in Europe), which was recently published by Fagbokforlaget. It focuses on Norway’s relationship to European integration.

How did No-voting Norway end up as the EU’s most integrated non-member? What really happened to the relationship between Norway and the EU in the period between the 1972 and 1994 referendums?

Rye addresses these questions in her book.

Two parallel blocs

The EEA Agreement is the link between two European cooperation organizations established after World War II: the EU and EFTA.

The foundation for the EU was laid as early as 1951, when France, Italy and Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg established the European Coal and Steel Community. Then, in 1957, the same countries created the European Economic Community (EEC).

The aim was to promote free trade between Member States as a means to ensure prosperity and peace between European countries.

A parallel trade bloc was formed in 1960. It consisted of the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, Portugal, Switzerland, Austria and Norway. Later, Iceland, Finland and Liechtenstein joined the bloc.

This bloc was EFTA – the European Free Trade Association. EFTA was created as an alternative to the European Community, which was eventually renamed the European Union.

Media graphic: Mads Nordtvedt / NTNU

De Gaulle feared the British were a Trojan horse

EFTA countries quickly began to orient themselves towards the EEC. Already in 1961/62, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Norway sought membership negotiations, but the process stalled when France’s President Charles de Gaulle vetoed Britain’s membership.

“For France and President de Gaulle, the EEC was a tool for restoring French greatness and taking leadership in Europe. They did not want competition from the UK in this endeavour,” says Rye.

Another factor that came into play was the development of what was then the EU’s major project, the development of a common agricultural policy. France was a major producer and exporter of agricultural commodities, and the United Kingdom was a major importer of agricultural commodities.

France, which wanted policies that supported high prices for agricultural products, therefore found it advantageous for the UK to remain outside the EEC until the agricultural policy was finalized.

“De Gaulle also had a strained relationship with the United States, and he feared that their close ally the United Kingdom would act as a Trojan horse for the United States and give them entry into Europe,” she said.

Norway, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Ireland once again applied for membership in 1967, and for the second time the French president stopped British entry.

Norway’s first No

When President de Gaulle resigned in 1969, negotiations quickly resumed.

The EEC was renamed the European Community (EC), and in 1993 European Union (EU) was formed. For simplicity, the abbreviation EU will be used throughout rest of this article.

The UK, Denmark, Ireland and Norway renewed their membership negotiations. The first three countries were admitted as members in 1973, but Norway said No in the 1972 referendum and remained outside the EU.

For the next three decades, one country after another announced that they wanted to leave EFTA to enter the EU.

EFTA shrank as the EU grew.

Troubled times in Europe

Europe in the 1970s was characterized by low economic growth and high unemployment. The EU and the EFTA countries were each trying to combat this development on their own, but because they were so intertwined in a Western European free trade area by this time, measures in one country quickly proved disadvantageous for partner nations.

“During this period, the desire for enhanced cooperation between the countries in Europe is thus growing stronger. In the 1980s, politicians are trying to achieve greater integration between the EF and EFTA countries. They only succeed to a limited extent, but the work they do then prepares the ground for EEA cooperation,” says Rye.

It then became clear to the countries what they needed to work on and that they needed new ways of working together.

The EEA was proposed while the Cold War was still a reality. In the late 1980s, the Cold War ebbed, and the barriers between the Eastern Bloc and the West disappeared. The Berlin Wall came tumbling down, and a united Germany was resurrected.

“The world suddenly looks completely different, and the geopolitical developments also mean new developments for Europe. Germany unites, and this results in a desire to connect Germany more closely to the EU. The authorities see a need to accelerate European integration and a unified Europe,” Rye said.

The Berlin Wall, the symbol of the east-west divide, was demolished in 1989 and Europe underwent major upheavals. Parts of the wall are preserved along Bernauer Strasse in Berlin. Photo: Shutterstock / NTB scanpix

That’s why the agreement is good and that’s why it’s bad

It was during this troubled period that the EEA Agreement found its form and was negotiated. The agreement shifted from being viewed as a permanent solution for countries that could not or would not become EU members, to considering it a transitional arrangement.

The parties believed that the agreement would only last for a short period until the various countries obtained full membership.

“The EEA agreement was created in a very special time context that makes the parties willing to stretch considerably,” says Rye.

The major upheavals in Europe, and the consequences this would have for EU cooperation in the form of new treaties and the desire for membership from a wide range of Eastern European countries, helped to draw the EU’s attention away from negotiations with EFTA countries.

“The negotiators in Brussels were eventually told to finish the negotiations and come to an agreement. All the parties were willing to be flexible because they didn’t think the agreement would be a lasting one. That’s why the agreement is good, and that’s why it’s bad,” Rye says.

“The EU opened up generous access to the EU’s single market and gave the EFTA countries trade conditions on par with EU members,” Rye said. “The EFTA countries, for their part, didn’t end up with much in terms of co-determination. They wanted co-determination but weren’t given a place at the table – and they accepted it.”

Most of the EFTA countries were planning to join the EU anyway. But not Norway.

Conservative Party leader Kaci Kullmann Five and Minister Eldrid Nordbø were central to the negotiations on the EEA agreement. (Facsimile of book published by Fagbokforlaget).

Decisive phase in Norwegian Europe politics

Politicians from different parties were leading the way in what would be a decisive phase in Norway’s Europe politics: they were Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of the Labour Party, and Centre Party (SP) leader Anne Enger Lahnstein.

“In Norway, then-Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland recognized that Norway might vote No again. She believed that the EEA agreement must be able to stand on its own,” Rye says.

When Norwegians then did say No to the EU for the second time in 1994, Norway already had a full EEA agreement in hand.

“This is an important reason for why Norway voted No in 1994; we had already reached a trade agreement with the EU. Over the course of three decades, the Yes-side’s main argument had been that Norway needed to join the EU to secure market access. The EEA agreement provided that access to the important EU market. So why should Norway then join the EU?” says Rye

The 2012 European Report describes the EEA Agreement as follows:

“Under the Agreement, Norway became linked to the European integration process in a new way. Since then, Norway has become increasingly closely tied to the EU.”

Why is opposition to European integration so strong?

The EU is a trade bloc, but it also aims to create closer integration between the European countries, like a kind of “United States of Europe”.

“The EU is at its core a political project that has used economic instruments to realize goals that are basically political. Norway always found economic integration the most attractive aspect of the EU. For Norwegian politicians on the Yes side, securing trade agreements, having equal market access – and predictability – were the main goals,” Rye said.

“When it comes to European political integration, it’s been hard to find enthusiasm for it from Norwegian politicians. Resistance was and is also high in large parts of the population,” she said.

For many countries, the desire to avoid a new war has been an important element of EU cooperation, but this argument has not been very prominent in Norway.

Rye says people in Norway are very pleased to be outside the EU. “That may have to do with how well off we are in many ways in Norway, compared to other European countries.”

Historically, the concept of a union has a distasteful ring to it in Norway. Other important factors include the desire to maintain the right to the country’s natural resources and opposition to the relinquishment of sovereignty demanded by EU membership.

“But even though we haven’t formally ceded our sovereignty to the EU, we have done so in fact,” Rye says.

Small ETFA and difficult EU

Today, EFTA consists of only four countries: Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland. The first three are part of the EEA Agreement, while Switzerland is completely outside it.

“Switzerland absolutely does not want to relinquish its sovereignty to the EU,” says Rye.

Several former Eastern bloc countries have gradually become EU members: the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Croatia and Malta and Cyprus.

Tensions within the EU are high in several areas. The financial crisis and the refugee crisis have obviously created deep divides between the north and the south, and between the east and the west. EU-critics are sailing on the wind of public sentiment.

“But perhaps the EU is becoming even more important than before because we are in an unpredictable and changeable era with strong forces in an unpredictable US, in a self-asserting Russia and in a China on the offensive,” says Rye.

Lise Rye

- Professor of European contemporary history at NTNU.

- Rye’s research has revolved around different forms and aspects of European integration.

- She was a member of the government-appointed European Commission (2010-2012) and teaches at NTNU's programme in European Studies.