The Detectives: Hunting toxic chemicals in the Arctic

What researchers are learning about the fate of chemicals in the Arctic, and how what they’re learning is changing international law and providing life-saving advice.

At first, it was a simple question: what exactly did oil pollution do to grey seals off the coast of Norway?

It was the early 1980s, and a young Norwegian ecotoxocologist, Bjørn Munroe Jenssen, was asked by Conoco Philips to find the answer.

The oil company was just beginning to look for oil in an area of the North Sea called the Halten Bank, off the coast of mid-Norway.

Jenssen and his colleagues knew that oil spills could contaminate seal fur, especially the pups.

“And actually more than 50% of them were polluted by these small tar balls, when they lie and rest, their fur gets contaminated. But we don’t think there are any large effects of that because it’s external contamination,” Jenssen said in the newest episode of 63 Degrees North, NTNU’s English-language podcast.

But Jenssen and his colleagues wondered if there were other contaminants getting into the bodies of the animals. So they did some blood tests. And what they found shocked them.

- You might also like: The dirtiest clean place on Earth

The poison book

Humans have been making and using chemicals for millennia, but their production skyrocketed in the 20th century. One chemical in particular, DDT, was discovered to be a potent insecticide by a Swiss chemist, Paul Herman Müller, in 1939. Its use during the Second World War saved many lives, by killing insects that carried malaria and typhus. Muller won the Nobel Prize in 1948 for his discovery.

But as the use of these and other chemicals increased, biologists began to see that they could have unintended and potentially Earth-shattering consequences.

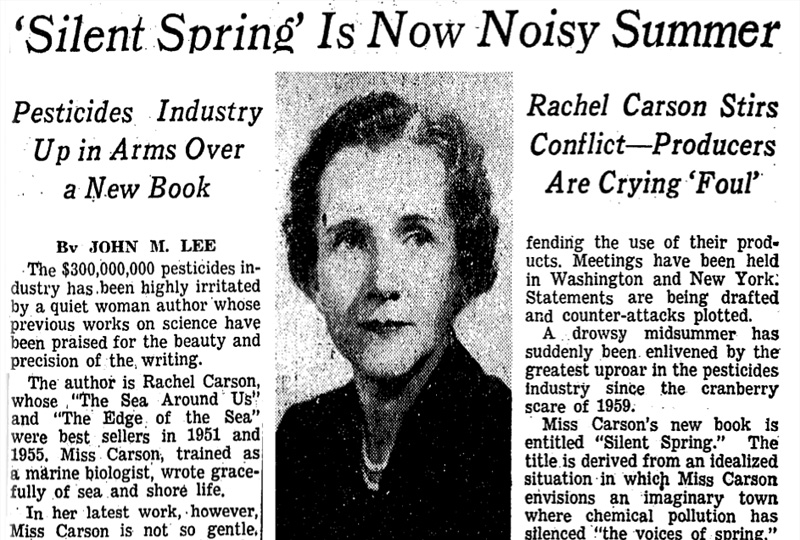

In September, 1962, an American marine biologist and author Rachel Carson

Carson published a book documenting just how damaging pesticides were to the environment. She privately called it “the Poison Book.” This work would help spawn the environmental movement across the Western world. It was called Silent Spring.

Rachel Carson’s book made national news. This clip is from The New York Times from 22 July 1962, page 86.

In spite of Carson’s work, chemical use continued to grow. They were used for everything from controlling insects and weeds to making materials fire-resistant. DDT had been banned, but many other chemicals were in widespread use.

Blood and blubber

The blood and tissue tests that Jenssen and his colleagues did contained an alphabet soup of substances.

We found that there were associations between blood levels of contaminants and levels of thyroid hormones, which are hormones that are very important for growth, for thermal regulation, for producing energy, and so on.

“We started to look for other contaminants like the PCBs, polychlorinated biphenols, and pesticides, like the old DDT, which was used a lot, and they were regulated in Norway at that time, but not globally,” he said. “And we found actually quite high concentrations of these compounds in the seals…. in their blood or in their blubber we examined. We even found levels in the brains of these small newborn pups.”

Then it was just a question of determining if the chemicals were affecting the contaminated animals.

The answer turned out to be: Yes.

“We found that there were associations between blood levels of contaminants and levels of thyroid hormones, which are hormones that are very important for growth, for thermal regulation, for producing energy, and so on,” Jenssen said. “So we thought that that might be a very important effect that could affect the survival or the health of the pups.”

Riding the wind

Jenssen didn’t just find these chemicals in seal pups. When he subsequently did tests on animals in arctic Norway, he found a huge spectrum of chemicals in them too — in everything from polar bear milk to Greenland shark blood.

Bjørn Munro Jenssen and a student take blood samples from a grey seal to check for contaminants. Photo: Private

But were all these chemicals coming from? They weren’t being generated in the Arctic, because there’s almost no industrial activity there.

What researchers gradually came to understand was that many of these pollutants can ride the wind or travel in ocean currents. If they are spilled or released somehow, some can vaporize and get carried into the atmosphere, where they ride the prevailing winds north. They might condense on their journey, and get deposited on the ground again, only to be vaporized when it’s warm enough.

And once they arrive in the Arctic, they tend to stay there, trapped in the snow, or as we now know, contained in the fat or blubber of the animals that live there.

And as Jenssen and other researchers have found, they have significant effects on the hormones of the animals that are contaminated.

- You might also like: Sharks contain more pollutants than polar bears

Native populations and health problems

Jon Øyvind Odland is a gynaecologist and global health researcher at NTNU and at UiT — the Arctic University of Norway.

As Bjørn Munroe Jenssen was documenting the kinds of chemicals that were accumulating in animals, particularly in the Arctic, Odland thought he would look at what was happening with native peoples in the far north.

Native people living in the far north who eat a traditional diet typically eat foods that are high in fat. And many of these substances concentrate in fats.

So when Odland studied native peoples in Chukotka, in eastern Russia, he found that they too, had high levels of contaminants in their blood. What’s more, they found a clear association between these high levels of contaminants and the effectiveness of childhood vaccines.

This posed a difficult challenge: Traditional diets are in many ways much healthier for people living in these most northerly areas. If native people switch to a more Western diet, they can develop other health problems, such as type II diabetes and heart disease.

“It’s the Arctic dilemma,” Odland said in the podcast. “The pollutants follow the food, the best nutrition you can get.”

Zooplankton on painkillers

Ida Beathe Øverjordet was one of Jenssen’s graduate students, studying mercury in the Arctic. Now she’s working at SINTEF, Scandinavia’s largest independent research institute, and continuing her work on pollutants in the Arctic.

Ida Beathe Øverjordet takes samples as part of her work studying where and how pharmaceuticals are found in the Arctic. Photo: Lacie Setsaas, SINTEF Ocean

Recently, she and her colleagues decided to see if they might pharmaceuticals in arctic creatures like tiny zooplankton in samples they took in Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago at 79 degrees North latitude.

It’s well known that pharmaceuticals find their into rivers, streams and lakes from treated wastewater in industrialized countries, but Øverjordet wondered if pharmaceuticals might somehow have also found a way to hitchhike to the north.

And they found them.

“We found quite high levels actually of painkillers, like ibuprofen and diclofenac. And also antibiotics and antidepressants we found in these tiny creatures living in the Arctic,” she said.

Listen to 63 Degrees North to learn more about the fate of these chemicals — and how science is helping policymakers do the right thing.

Selected references:

(2017) Potentiation of ecological factors on the disruption of thyroid hormones by organo-halogenated contaminants in female polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from the Barents Sea. Environmental Research. vol. 15

(2017) Relationships between POPs, biometrics and circulating steroids in male polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Svalbard. Environmental Pollution (1987). vol. 230.

(2016) Circumpolar contaminant concentrations in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and potential population-level effects. Environmental Research. vol. 151.

(2021) Sociodemographic factors influencing the health of pregnant women: Changes in the arctic countries over the past decades. Akusherstvo i Ginekologiya. vol. 2021 (6).

(2020) Health risk modifiers of exposure to persistent pollutants among indigenous peoples of Chukotka. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH). vol. 17 (1).