How researchers halved a bed’s carbon footprint

Researchers calculated the total carbon footprint of a bed. Then they discovered it was possible to halve it.

“We’ve revealed the total environmental impact by looking at the bed’s entire lifecycle, from use of the materials, through production to final incineration,” says SINTEF researcher Mathias Irgens. “Then we looked at how we could reduce the carbon footprint.” He began working on the WondRest project when writing his master’s thesis two years ago.

The researchers measured the footprint by carrying out a life cycle analysis, or LCA, which is a method for evaluating the total environmental impact of a product or process throughout all the stages of its lifecycle.

“We performed the LCA using the analysis tool Simapro,” Irgens explains. “This software can be used to evaluate the environmental effects of the choices made during a product development process. This gave us an idea of the total environmental impact of the various phases of the bed’s lifecycle.”

SINTEF researcher Mathias Irgens presenting the results from the life cycle analysis at the “Future of sleep” conference in Åndalsnes. Photo: SINTEF

From cradle to grave

The LCA revealed that the continental bed’s total carbon footprint was to 610 kg of CO2 equivalents. This included production of the bed, the replacement of the top mattress once during its lifetime, and incineration of the bed as residual waste at the end of its life.

We’ve calculated how we can achieve a circular business model that is profitable for all parties involved

“To put things in perspective, this equates to a return journey from Oslo to Nice for two, or one and a half years’ purchase of clothes and shoes for an average Norwegian”, Irgens explains.

The researchers then looked at changes that could be made to the bed’s design, as well as how to extend its lifetime and modify the final stage.

- You might also like: Urgent need to commercialise CCS

Various lifecycles examined

“Currently, the entire bed is incinerated, but we’re working on options for both re-using and recycling all the materials”, says Irgens, who has spent a lot of time running scenarios and calculating which options are cost-effective.

“For example, we looked at the effects of reducing the steel component, increasing the amount of recycled textiles and modifying some bed components”, says Irgens.

The researchers, from both SINTEF and NTNU, also propose to extend the bed’s lifetime by, among other things, introducing maintenance schemes that will make it possible to replace bed components as and when necessary.

“By introducing ideas that extend the bed’s lifetime, enabling a transition to more environmentally friendly materials, and also by finding a design concept allowing for easy recycling of the bed’s various components at the end of its life, we have succeeded in halving the carbon footprint”, says Irgens.

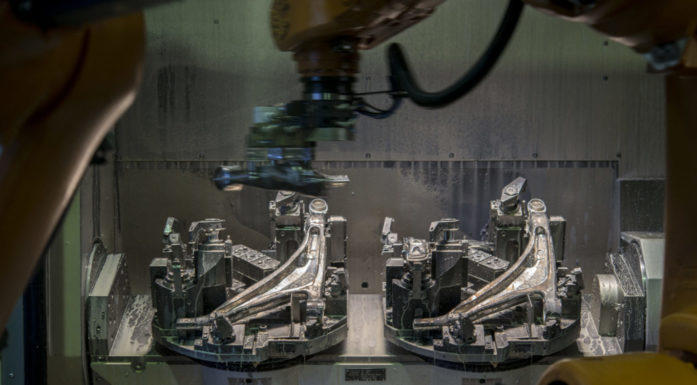

Some of the team at work. From the left: Trond Svendsen from Måndalen Trevare, Håkon Stokke Sæther from Recticel, Hege Rønning from J.O. Moen Miljø AS and Lars Stenerud from Wonderland. Photo: Eller Elin Herjehagen

The project in now in its final phase, involving the development of a prototype using new materials and a new design.

“Overall, it will contain fewer, but more environmentally friendly, materials”, says Irgens. “It will also be resilient over a long lifetime and, not least, will be as comfortable as the older models, a factor that has been an important project criterion from the outset.”

Wonderland has already started using some recycled plastic and has increased the proportion of recycled textiles in its products by 40%. As well as working on the environmental aspects, the researchers have been mindful of the need for bed production to be profitable.

“We’ve calculated how we can achieve a circular business model that is profitable for all parties involved”, says Irgens.

The project will be completed in spring 2023.

“By then, we’ll have a prototype that will enable Wonderland to present a circular business model to the market, based on the results revealed by the project”, Irgens concludes.