Organs grown on microchips may offer a quantum leap for women’s health

Women’s bodies and their health in general have for too long been assigned low priority in the field of research. But an innovative and extraordinary technology may now offer us new treatments for conditions such as endometriosis.

Today, the development of new drugs is a time-consuming and expensive process. It takes on average more than ten years to launch a new drug onto the market. Much of the reason for this is that new drugs still have to be tested on experimental animals, and about 90 per cent never reach the market. The transferability to humans of new and highly promising drugs is simply not good enough. Historically, medical conditions typical to women have been the focus of less research that those of men, resulting in a marked gender inequality.

But what if a technology existed that could make the development of drugs advance more quickly? This is the question that researchers all over the world are currently working on. The technology is called ‘organ-on-a-chip’ and is the result of combining the following two elements into a single approach:

- Mini-organs: These imitate the functions of the real organs that we carry in our bodies. Also known as ‘organoids’, they are cultivated from a variety of different cells, growing into tiny ears, hearts or small intestines.

- Microchips: These are based on the same technology that we use in our computers and mobile phones.

New endometriosis drugs

Endometriosis is a condition in which tissue similar to the membrane lining the uterus starts to grow outside the uterus. On average, it takes seven to ten years for a woman to obtain a correct diagnosis. The condition can be very painful and many women receive incorrect diagnoses because, in the majority of cases, it can only be proven with certainty after keyhole surgery. According to the Norwegian Endometriosis Association, as many as ten per cent of women are estimated to have this condition.

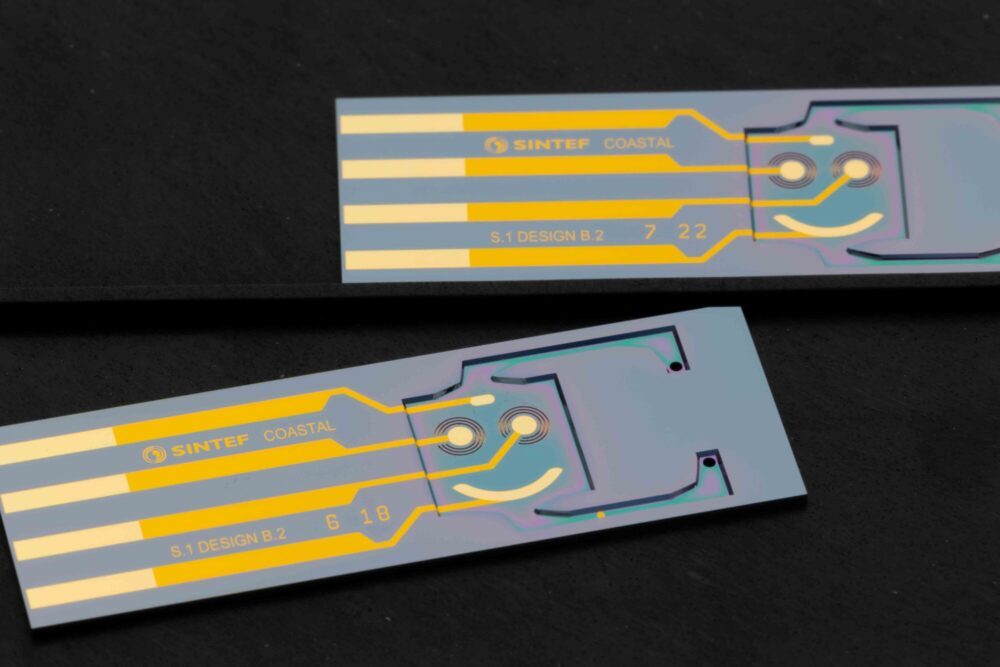

Lab-on-a-chip. These are so-called BioMEMS chips. The lower example exhibits two black holes, on the right, through which fluids can flow. Flow is measured in a miniature sample chamber before the fluids flow out again. This principle has many applications in the fields of medicine and biology. The chips pictured here are taken from a project called COASTAL, being carried out at SINTEF MiNaLab with the aim of reducing the negative impacts of marine algal blooms. Photo: Mari Aftret Mørtvedt/SINTEF Digital

There is thus a great demand to identify new approaches for faster diagnosis of the condition, and this is where mini-organ technology comes in.

Because everything starts with mini-organs, which are commonly made up of different types of cells, some of which are as distinct as individual snowflakes in terms of their shape, and may have different functions. Today, the technology has advanced to the stage at which we can create three-dimensional mini-organs containing different types of cells. This approach is entirely new, differing from methods that involve investigating single cells in isolation. Mini-organs are kept in a pale pink, nutrient-rich fluid in receptacles no bigger than a thimble.

Today, the technology has advanced to the stage at which we can create three-dimensional mini-organs containing different types of cells.

At the University of Leuven in Belgium, we have recently succeeded in cultivating mini-organs that can imitate endometriosis using cell samples taken from women suffering with the condition. This now allows us to test new drugs for the treatment of endometriosis. The mini-organs provide us with faster and more accurate results because the cells are taken from a woman’s body and not from an experimental animal. Our work has led us to discover that endometriosis develops differently in different individuals, indicating that the condition cannot be treated with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Making a ‘mini laboratory’

When mini-organs are kept in nutrient-rich lab receptacles, it is difficult to investigate them in isolation. For this reason, researchers have now succeeded in placing them on microchips, hence the term ‘organ-on-a-chip’. Instead of using electronic circuits to promote fluid flow, the mini-organs obtain their nutrients via channels no wider than a human hair that transport fluids into the chips. The microchips can thus ‘build a body’ around the mini-organs. This enables us to subject them to movements that simulate processes such as breathing.

At SINTEF, we are currently investigating this technology with a view to creating a ‘lab-on-a-chip’. This will enable us to test new drugs more quickly and efficiently than is possible today. At present, this process is carried out in large analytical laboratories that are not designed to deal with miniature mini-organs. Advanced sensors and measurement systems can be used to identify the properties that individual organs possess, and this in turn helps us to evaluate the efficacy of different drugs. In the future, this will require the development of miniaturised analytical platforms, such as those currently being developed jointly by SINTEF and the University of Oslo.

Placenta on a microchip

Even though this technology will not be mature for several years, it has already demonstrated that in some cases it can model the function of the human body more precisely than is possible using experimental animals. In the USA, opportunities have already been created for the use of alternative approaches to the use of animals in processes leading to the approval of new drugs.

This is the future, and it is now within our reach. Researchers have already used microchips to simulate both the placenta and the process of menstruation. The team that succeeded in cultivating placenta cells on a microchip were able reproduce the transfer of drugs from a mother to the placenta. This provided important information for understanding how an embryo may be affected by a mother’s drug intake.

If we are to succeed in achieving true equality for men and women in our health services, it is crucial that we apply these new technologies. The application of ‘organ-on-a-chip’ technology will make it equally natural for researchers to work with all human bodies, male or female. At present, we have barely left the starting blocks. However, this technology has the potential to lay the foundations for our future understanding of, and investigations into, other health challenges related to women’s health, such as cardiac and pulmonary conditions.

It might sound like science fiction – but soon it will be only all about the science.

This article was first published in the Trondheim newspaper Adresseavisen on 8 March (International Women’s Day) and is reproduced here with the permission of the paper.