Research is helping us to develop healthier and more climate-friendly protective footwear

Protective shoes are stiff and heavy and made primarily for protection. Many people feel they’re more trouble than they’re worth. But research is coming to the rescue, with better ergonomics and a reduced climate footprint.

“Systematic efforts to achieve sustainability in the footwear sector are the work of pioneers”, says SINTEF researcher Tore Christian B. Storholmen.

He and his colleagues have recently been interviewing a selection of industrial workers to find out exactly where the (protective) shoe pinches. Their findings are resulting in innovative and lighter models – with a reduced climate footprint.

Key in the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders

For thousands of industrial workers in Norway, protective footwear is part of their everyday clothing. It protects the feet and toes from impact and crushing injuries, from piercing by sharp objects and corrosion by chemicals. Workers take thousands of steps during their long working lifetimes, each and every day, and protective shoes play a key role in the prevention of occupational musculoskeletal disorders.

But protective footwear is also a product of the clothing and footwear industries, which are known to be problematic in terms of their environmental impact. The clothing industry accounts for ten per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, largely due to overproduction and short product lifetimes. Huge volumes of clothes and shoes are discarded after only short periods of use, although some of this is unavoidable in the case of protective footwear.

“A protective shoe is intended to offer workers protection against their hazardous everyday surroundings”, says Storholmen. “But as soon as it no longer provides this protection, it has to be replaced”, he says.

Storholmen is currently coordinating a project called Lightfoot, which is aiming to develop an entirely new type of protective shoe. The new models will be more comfortable to walk in, while at the same time meeting all the requirements stipulated for protective footwear. The project, which is a joint collaboration between SINTEF and the Norwegian company Wenaas Workwear, also aims significantly to reduce the climate footprint of protective footwear.

Long, long days on steel and concrete

Following almost 30 in-depth interviews, the SINTEF researchers obtained an excellent insight into how industrial workers feel about their footwear, health, sustainability and exactly what causes their shoes to wear out.

“We’ll be using these findings to make better protective footwear”, says Storholmen.

Many of the interviewees related stories of pain and discomfort in their feet and lower legs after long days on hard steel and concrete surfaces.

“It’s not uncommon for a worker to take between ten and fifteen thousand paces in a single day”, says Storholmen. “So, it’s no surprise that this puts a significant strain on the legs. This is why many are looking for shoes with better soles”, he says.

The problem with protective shoes is that they’re made up of so many different materials”, explains Storholmen.

“A shoe may easily contain up to 40 different materials”, he says. “All of which have a major influence on the degree of protection a shoe offers, its durability and performance. At the same time, this comes with environmental costs linked to sourcing of the raw materials”, he says.

Design determines emissions

“Eighty per cent of the climate footprint of these shoes is determined by decisions taken in the design phase”, says Jon Halfdanarson, who is a Research Manager at SINTEF Manufacturing.

Structured and research-based design entails working with a given insight before actually commencing the design process.

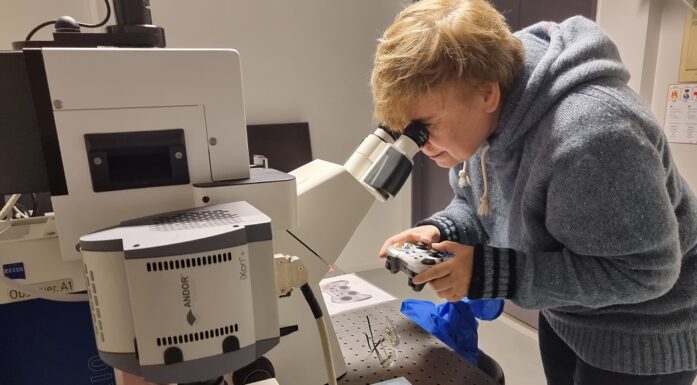

“Work cannot be founded on assumptions”, says Halfdanarson. “Our point of departure is the highest quality protective shoe that Wenaas currently manufactures. We have completed a comprehensive analysis of its life cycle – a so-called Life Cycle Assessment, or LCA. This enables us to see how individual component materials contribute negatively to the product’s climate footprint”, he says.

An LCA enables scientists to obtain knowledge about the factors that act to produce a negative footprint. Researchers at SINTEF have set themselves a target of halving the existing climate footprint of these products.

“It looks as if we might succeed, although we haven’t yet made final decisions about all of our materials selections”, says Storholmen. “The stringent requirements linked to protective footwear make it a demanding task to reduce the number of component materials or replace them with more eco-friendly alternatives”, he says.

The researchers are currently being rather secretive about how the new shoe will be manufactured, but they are promising to give us some exciting news in the not too distant future. According to Storholmen, they have made a number of innovations that will lead to major improvements in comfort, as well as ergonomic benefits.

Other shoe manufacturers will also be able to benefit from the work completed during this project.

“We intend to prepare a set of guidelines for shoe manufacture, showing how LCA analyses can be used as part of the design process”, says Halfdanarson. “This will help designers to work even more systematically and boost awareness of their responsibilities”, he says.

Pressure from customers

“Walking in protective shoes is universally regarded as a nuisance”, says Product Manager Glenn Bingen at the company Wenaas.

His dream is to be able to make protective shoes that are as comfortable as a pair of trainers.

It’s not uncommon for a worker to take between ten and fifteen thousand paces in a single day. This means that protective shoes have a major influence on people’s health. Stock photo: Andrey Popov/iStock

“Weight isn’t the only factor”, says Bingen. “The construction itself, which among other things includes a rigid and front-heavy toe cap, makes it difficult to give protective footwear the same properties as standard shoes. We’ve tried to incorporate more technical materials, for example to promote heel cushioning, but this hasn’t so far resulted in any noticeable improvement”, he says.

It was the company Wenaas Workwear that took the initiative for the Lightfoot research project. As well as the need for a more comfortable shoe, they noted that their end users were increasingly demanding more sustainable products.

“We also manufacture other types of workwear, and there is already a major focus on sustainability in these sectors”, says Bingen. “Requirements stipulate that all materials must be recyclable, and that less water be used in the production of cotton fabrics. Footwear has probably been the subject of less attention than other types of clothing, but we can see it coming”, he says.

Wenaas is working together with the Italian company Orion Group in connection with shoe manufacture. The use of locally-sourced materials with the aim of reducing freight miles is one of the measures being implemented in order to reduce the climate footprint.

“There are a great many things in the composition of a shoe that influence carbon emissions”, says Bingen. “SINTEF’s LCA approach helps us enormously when we come to select our materials. At the same time, extending the lifetime of the shoes is in fact the best thing that we can do. This has a major influence on the climate footprint.”, he says.

Aker BP, Equinor and OneCo are acting as partners in the Lightfoot project, which has received funding from the Research Council of Norway. These companies are contributing with HSE-related expertise and are playing a key role in the testing and evaluation of prototypes.