Smart measures to reduce your electricity bill

Would you adjust your electricity consumption if you received a notification on your mobile phone telling you when electricity was going to be most expensive the following day? Research shows that good information can influence our energy consumption.

It’s winter, and in Norway the short days and low sun angle mean the winter cold will settle over the country. As a result electricity prices will inevitably soar.

In a country where many people use electricity to heat their homes, people wonder how they can reduce their electricity bills. Maybe turning off the electric radiators and using the wood-burning stove instead would help, even if it might mean waking up to a glacial house.

Another option is not to use so much electricity during the most expensive hours.

“It is actually possible for households to adapt their electricity consumption according to the price of electricity, thus reducing their electricity bill. This type of adaptation also has positive effects for the power system,” explained Matthias Hofmann, a researcher at Statnett and NTNU.

Balancing production and consumption of electricity

Avoiding electricity consumption during peak demand is not only good for Norwegians’ electricity bills, but also for the power system as a whole. Reducing consumption peaks can help prevent the power grid from becoming overloaded during periods of high demand in winter.

Electricity prices are often highest when the consumption peaks occur. Hydropower producers must ensure that they have enough water in their reservoirs to meet demand at all times. That is why they raise prices when water levels in the reservoirs drop.

Electricity prices act as a signal that reflect scarcity both in the grid and production capacity. These high prices play a crucial role in balancing the power system. Electricity production and consumption must always be in balance.

When production is low and consumption is high, prices rise to make it profitable to increase production and reduce consumption – and vice versa.

“Consumers who respond to prices by using less electricity help reduce the consumption peaks. In turn, this makes the entire power system cheaper, as less production is needed from expensive power plants that only operate for short periods of time,” said Hofmann.

Saving money on a more efficient power system

Another positive effect is that the load on the power grid is reduced.

Matthias Hofmann is a senior adviser at Statnett and a PhD candidate at NTNU and the CINELDI research centre.

The power grid must be designed to handle the hours of peak consumption. As consumption peaks decrease, so does the need for investments in the grid.

“Remember, it is we consumers who ultimately pay for the expansion of the power grid. A more efficient power system is therefore something we all save money on,” he said-

Norway is unique in that most households have electricity contracts based on spot prices, meaning the electricity price varies from hour to hour. In almost all other countries, customers have fixed-price contracts, Hofmann said.

In addition, all Norwegian electricity customers have a smart meter that records electricity consumption on an hourly basis. So, instead of calculating an average price, it means that an electricity bill is based on when the electricity was used during the day and its price at that specific time.

This enables Norwegian consumers to directly lower their electricity bills by reducing their consumption during peak hours.

A price experiment

Through the CINELDI research centre, Hofmann has studied how Norwegians respond to variations in electricity prices. Do Norwegian households care that the price goes up? Do they reduce their consumption during the hours of the day when electricity is most expensive? How much does alleviating the load on the power grid help?

To find out, he conducted a price experiment involving Norwegian households.

In the iFleks study, researchers invited households across Norway to participate in a price experiment, where they were given artificial prices over a couple of winter months.

“We gave them very good information. We sent them text messages, telling them that prices would be high the next day, and at what time. We also gave them information about how much money they could save if they reduced their consumption by a certain amount. It was then up to them whether they took any manual measures themselves, such as lighting the wood-burning stove or charging their electric vehicle at a different time of the day.”

Electricity customers take measures when they are aware of price differences

The results showed that half of the households in the study responded to price changes and did something to reduce their electricity consumption during high-price hours.

“They received information about what it meant in monetary terms, and it was this that had an effect.”

In 2022, when Hofmann had completed the price experiment, Europe entered a power crisis. Reduced gas deliveries from Russia led to a sharp rise in electricity prices, which Norwegian electricity customers also felt first-hand. It was no dream situation for electricity customers, but it gave Hofmann the opportunity to study whether Norwegians would change their consumption in real life, and not just in the experiment.

“We saw that as many as 80 per cent of households took measures to reduce their electricity consumption,” said Hofmann.

Much to gain from automated solutions

Despite this, research shows that few people take advantage of the opportunity to adjust their electricity consumption when prices vary from hour to hour.

“We see that most households respond to changes in electricity prices on a more long-term basis, from week to week or month to month. They might lower the indoor temperature and, in doing so, consistently use slightly less electricity, as the average price is high during certain periods. But they tend to pay less attention to the hourly prices on a day-to-day basis,” said Hofmann.

A lot could be gained if electricity usage could be automated, so that part of the consumption is shifted away from high-price hours without people having to do anything themselves.

Potential of automatic control

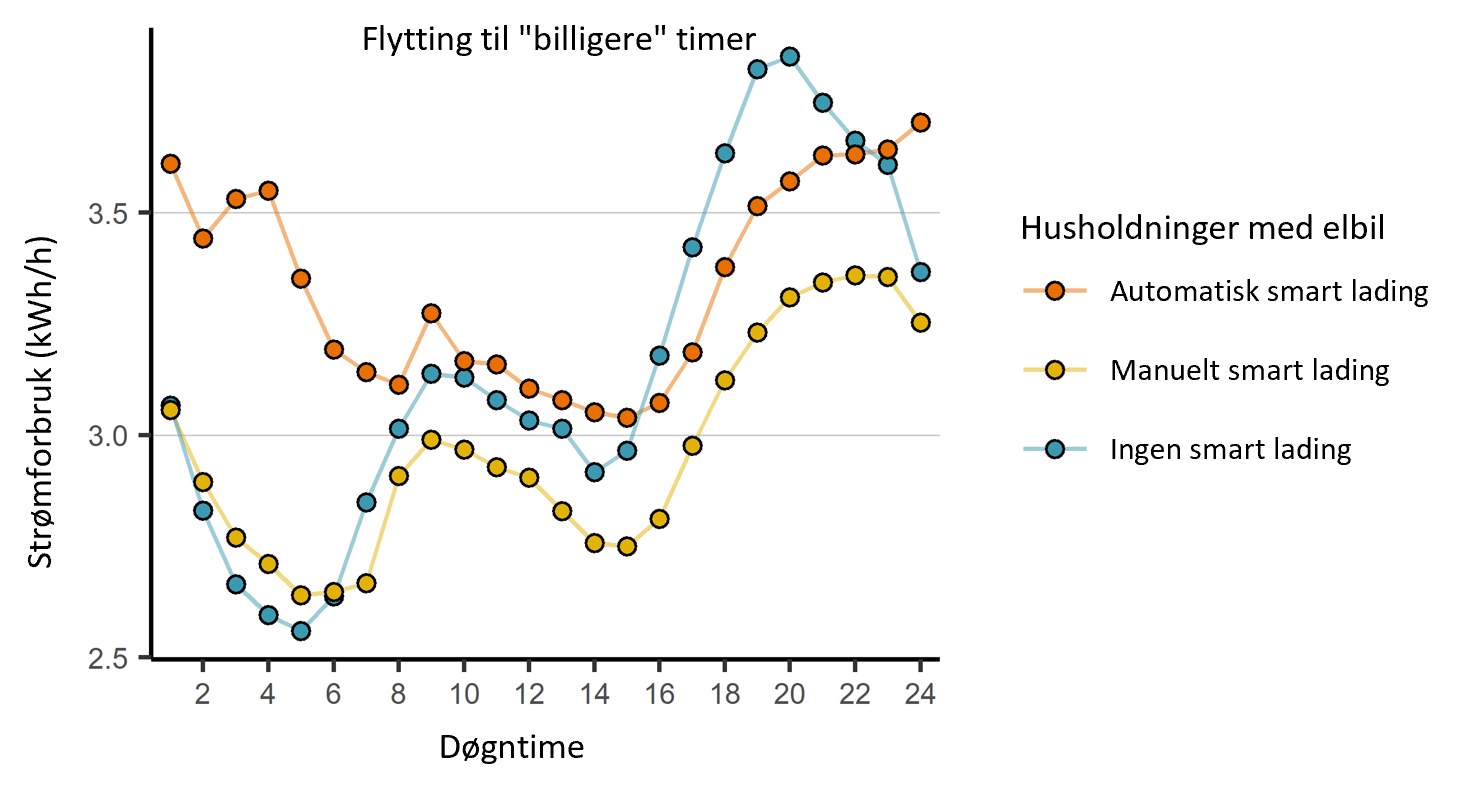

“People who had electric vehicles with automatic smart chargers reduced their electricity consumption by an average of 16 per cent during high-price hours. But we also saw that people who were keen to avoid expensive hours and manually controlled their electric vehicle charging were able to reduce their electricity consumption by between 11 and 13 per cent.”

By contrast, electric vehicle owners who did not care about the price and charged whenever they wanted only reduced their electricity consumption by 5 per cent.

“This illustrates the potential of automatic control. But it requires an investment, which costs money. Good information about the advantages and disadvantages of different solutions is important to enable people to make informed choices about what works best for them.

Households with electric vehicles and automatic smart charging reduced their electricity consumption during the most expensive hours in the afternoon by automatically shifting their charging to ‘cheaper’ (billigere) hours at night during the energy crisis in 2021–2022. (Translation of text in graphic: Strømforbruk: Consumption; Flytting til “billigere” timer: Shifting to cheaper hours; Døgntime: Time of day; Husholdninger med elbil: Homeowners with an electric car; Automatisk smart lading: Automatic smart charging; Manuelt smart lading: Manual smart charging; Ingen smart lading: No smart charging.) Illustration: Matthias Hofmann

“If it turns out that smart chargers are always the most cost-effective option, we could consider making their use a requirement for all electric vehicle owners. This would prevent people from choosing inferior solutions,” said Hofmann.

‘Everyone’ can save money through good information

He has also taken a closer look at how low-income families respond to higher electricity prices.

“It is often said that people who have low incomes have fewer opportunities to do something about their electricity consumption – that they are less flexible. They may not have an electric vehicle that can be used to shift their electricity consumption to cheaper hours. But I saw no difference between low-income households and others. They are just as flexible and take advantage of the opportunity to reduce their electricity bills to the same extent,” he said.

Hofmann also observed that households’ responses to price changes were ‘either-or’. People generally respond to information like ‘it’s expensive now’ or ‘it’s cheap now’, but they respond less to information about how much more expensive or cheaper the electricity is at different times.

His advice is therefore to give customers even better information.

“This information can be shared in many ways. For example, power companies can send push notifications – messages that pop up on smartphones when the prices change – with suggestions for measures you can take and exactly how much money can be saved,” he said.

These solutions are already available as services provided by several electricity companies.

Lower grid load with smart transmission fees

He also believes more can be done to get people to react to fluctuations in transmission fees.

“Currently, transmission fees are something that are difficult for most people to grasp. The price is based on an average for three hours where you use the most electricity each month. The hours are difficult for individuals to predict, and only become known later on,” he said.

Therefore, most people only pay attention to the spot price, which comes from the electricity market and is announced one day in advance.

“My research shows that households’ maximum electricity consumption doesn’t necessarily coincide with the times when the grid is under the greatest load,” the researcher pointed out.

The total consumption is what matters for the power grid. It is therefore important to look at when all end users collectively consume a lot of electricity in a specific area, not when each individual uses the most.

“To help reduce grid investments, it might be a good idea to see whether the transmission fee can be more closely linked to the overall load on the grid. In any case, it’s always important to provide good information and preferably notify households in advance about when the grid is heavily loaded so they can adjust their electricity consumption accordingly,” said Hofmann.

Source: Matthias Hofmann ‘Implicit Demand Side Flexibility as an Alternative to Investments in the Transmission Grid’ (ISBN 978-82-326-8441-0)