What can we learn from a 100-year-old housing experiment?

More than 100 years ago, visionary and socially engaged individuals were at the forefront of a groundbreaking cooperative housing project in Trondheim. Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap at Rosenborg is a relatively unknown gem.

In a study published late last year, three architects explored the history of Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap (TKB) in light of social and political trends in today’s Norway. TKB was and is a groundbreaking project from both a social and architectural perspective.

NTNU professors Eli Støa and Steffen Wellinger, along with Nina Berre, a professor and head of department from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), are behind the study.

They have investigated how elements of TKB’s organizational and architectural principles are still relevant today.

In Norway’s largest cities, the needle’s eye for entering the housing market is tiny. And new urban housing complexes are often compact, with little architectural quality or green space.

“Our narrative of TKB’s history adds knowledge to 20th-century Nordic housing planning and is relevant to today’s housing debates…. it holds inspiration for future housing models, when it comes to area layout and density, architectural qualities and adaptability, conditions for social life and organization,” the authors wrote in their article.

They argue that the TKB model is a case for studying the interaction between housing and society.

Overcrowding and lack of daylight

Crowded living conditions, poor sanitary and technical standards as well as a lack of daylight and green space characterized the housing situation for the working class in Norwegian cities in the early 20th century.

The housing issue was therefore high on the political agenda in Norway from the 1920s.

In addition to improving quality, questions were related to how to finance and reduce the costs of new housing.

The dominant political parties, the Liberal Party and later the Labour Party, advocated that municipalities should take greater responsibility for the development of social housing.

Focus on a general improvement in housing standards and increased social awareness among planners and architects became decisive. This led to examples of residential areas that 100 years later can still be considered innovative and significant for future housing solutions.

The old residential area at Rosenborg, which is still attractive and works well today, is a good example.

The green space between the houses serves as a social gathering place, a play area for children and a recreation area for residents. The photo shows residents gathering for a centennial celebration of the cooperative. Photo: Steffen Wellinger

The third housing sector

With the strong economic growth in Norway in recent decades, the housing situation for most people is hardly comparable to the situation 100 years ago.

Nevertheless, the housing issue is back on the political agenda.

A growing proportion of the population in the largest cities cannot afford to own their own home. The housing market is described as an “inequality machine” and as an object of speculation instead of a social good.

A third housing sector has been proposed as an alternative for groups that fall between the ordinary housing market and municipal rental apartments for the disadvantaged.

Examples of third sector housing include housing foundations, tenant cooperatives and other forms of public rental housing and price-regulated cooperative ownership.

So far, the debate has not led to major political changes, but an increasing number of examples of third sector housing are under development.

Among these are projects based on self-construction and a high degree of resident involvement, non-commercial ownership models and sharing solutions that can result in less resource use and lower costs.

Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap can be an inspiration for such alternative housing models.

Norwegian housing policy: From housing shortage to housing construction to new housing shortage

After World War II, the housing issue was once again high on the agenda – just as it was in the 1920s. Due to the large housing deficit after the war, ensuring good housing for all became one of the cornerstones of the Norwegian welfare society.

The foundation for what is known as the “Norwegian model” of housing policy was laid even before 1940 and was further developed during the following decades.

The model had three pillars:

1) The state, with responsibility for legislation and main responsibility for financing through the Statens Husbank (established in 1946)

2) The municipalities, which were responsible for spatial planning and for making land available

3) Housing associations and private actors, which were responsible for the actual construction of new homes.

This model functioned until the early 1980s and was seen as successful in improving housing standards for the majority of the population and increasing the proportion of homeowners.

It also supported social justice through state bank financing and price controls.

When a political shift occurred in 1981 and the Conservative Party came to power, the housing and credit markets were liberalized. Public authorities lost their central role in housing development. Private developers became the main players.

This led to large fluctuations in house prices and a more segregated housing market.

Today, a growing proportion of the population in the largest cities cannot afford to own their own home.

Visionary architect

TKB was established in 1922 and is the second oldest, active housing cooperative in Norway. The development of the TBK area was led by architect Sverre Pedersen. He was central to the debates about housing construction in the early 20th century.

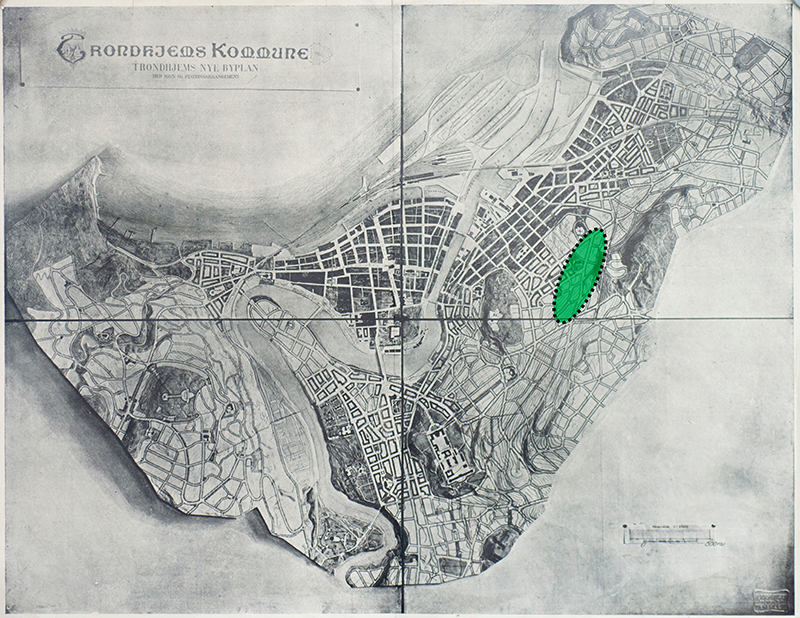

Architect Sverre Pedersen’s plan for Trondheim, from 1912. The area where TBK is located is coloured in green.

As both an architect and urban planner, he became a leading figure in reformulating international ideology for urban planning and architecture in Norway.

In 1910-1912 he developed the city plan for Trondheim, with a focus on the outskirts of the city.

In 1920, Sverre Pedersen became the first professor of urban planning in Norway.

When he taught his students at the Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH), he was focused on teaching them that their task was to improve Norway’s general housing conditions and solve housing problems for the poorest groups.

Bottom-up initiative

Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap was a bottom-up initiative. It was initiated by construction workers and founded by their union. They also participated in the construction of the homes themselves.

Trondheim Municipality guaranteed loans and granted a down payment contribution that covered 30 per cent of the construction costs of the cooperative.

From the start, most of the residents were workers, craftsmen, as well as elected officials and employees of the workers’ unions. Inspired by the Egne Hjem movement (Own home), workers were to have the opportunity to own their homes and not be dependent on greedy landlords.

Cooperative ownership made this possible.

- You might also like: First out to buy and sell neighbourhood electricity

The Pearl of Rosenborg

Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap is an example of how international and local ideas about urban planning and architecture were combined in Norway.

TKB balances tradition and modernity.

Architect Sverre Pedersen’s zoning plan for TKB followed the lines of the terrain with adaptation to the area’s topography.

The homes that were built at Rosenborg are 2- and 4-person homes that contain a total of 86 apartments.

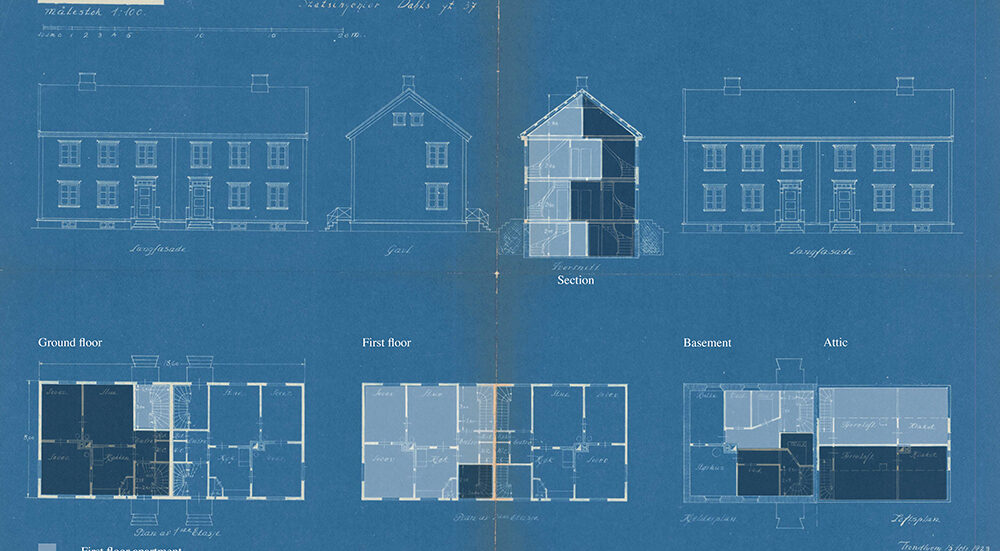

Letting sunlight into each apartment was an important principle for architect Trygve Klingenberg, who designed the homes.

Each of the almost equal-sized rooms has at least one fairly large window. An open door between the two rooms that filled the width of the house allowed light to fill the space.

In combination with relatively high ceilings, this provided good daylight conditions and spatial qualities. The windows also provide views of green common areas and the landscapes around Trondheim fjord.

Architect Trygve Klingenberg’s floor plans for the houses at Rosenborg. Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap has so far been unknown in international housing research and is also little mentioned in Norwegian literature.

Own garden, own entrance and own staircase

The idea was that each family should have access to green recreational areas, including access to a small private garden. This was made possible by giving each apartment its own entrance and its own staircase that went from the basement to the attic.

An approach to a staircase like this is often considered unnecessarily space-consuming and expensive, but it contributes to an increased sense of privacy, even if you live close to other families.

The development at Rosenborg was inspired by the international garden city movement.

Here’s what the homes are like today

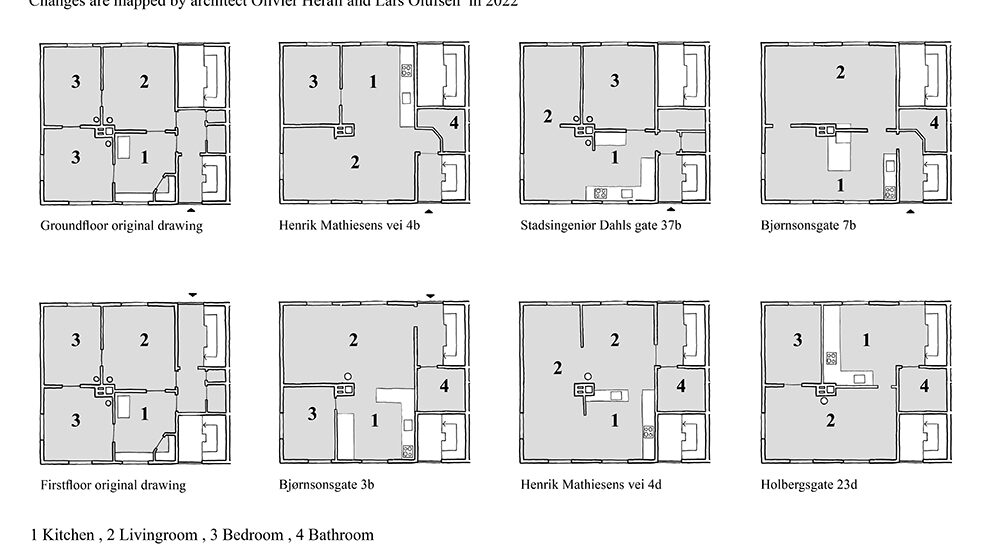

Naturally, several changes have been made to the interior throughout the houses’ 100-year history. For example, storage and laundry rooms in the basements have been converted to residential purposes.

The simple and robust type of housing has proven to be adaptable.

Few changes have been made to the exterior. Upgrades to the exterior have primarily been improvements to entrance areas, and replacements of exterior doors and windows.

The improvements have focused on replicating the original appearance.

Solid construction, good dimensioning and a clear architectural expression mean that TKB’s buildings still retain most of their original character.

The floor plans on the far left show how the room layouts were originally. The other floor plans show how the room layouts have changed in the homes today. Floor plans by Olivier Herail and Lars Olufsen

Sustainable cities

What lessons from Rosenborg can we take with us into today’s housing construction?

A topic in today’s debate about sustainable cities is bringing green areas into dense urban residential areas. The homes in Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap are located integrated in three continuous green areas.

The green areas are important for recreation, health and well-being, as an arena for social activities in the neighbourhood and for biodiversity through both crops and other vegetation.

The buildings’ layouts, construction and choice of materials make it easy to transform, based on new needs and conditions, without changing the basic character of the buildings.

The adaptability probably contributes to the fact that the area per resident in TKB is over 20 per cent lower than in similar housing in the rest of Trondheim.

The architectural qualities of the buildings also have an impact on current and future living conditions in Trondhjems Kooperative Boligselskap. The architectural expression is simple and well-balanced.

The houses are built in a familiar style with roots in local building customs, inspired by the Trønderlån house type. Solid material choices make repair and modification possible.

Reference: Berre, N., Støa, E., & Wellinger, S. (2024). Rare yet relevant: Trondheim Cooperative Housing Association. Planning Perspectives, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2024.2401834