Unlocking the secrets of Viking and medieval walrus tusk trade

Two tiny Scandinavian settlements in Greenland persisted for nearly 500 years and then mysteriously vanished. Their disappearance has been blamed on everything from poor agricultural practices to a changing climate. But what if the real reason was the walrus tusk trade?

More than a thousand years ago, an intricate network of Norse traders plied the dangerous waters of the North Atlantic in open boats, their ships laden with precious goods – walrus tusks and hides –destined for the Norwegian coastal cities of Trondheim and Bergen.

The likelihood is that the whole of Eurasian demand during the Middle Ages was heavily focused on Western Greenland.

Large numbers of walrus ivory finds from the period have been found throughout Northwestern Europe, showing that walrus ivory was a global commodity, said James Barrett, a professor of medieval and environmental archeology at NTNU University Museum.

“At the moment, the farthest south and east that there are discoveries of these skulls, from Greenland, is Novgorod and Kyiv,” he said on the latest episode of 63 Degrees North, an NTNU podcast.

This expansive trade network made Barrett and his colleagues curious. What was source of all that walrus ivory? It could have come from almost anywhere in the Arctic.

So the researchers used a range of high tech tools, from ancient DNA analysis to stable isotope analysis, to look at the ivory objects and walrus skulls that survived from this period to figure out where the walruses originated.

And what they found shocked them.

- You might also like: Fantastic ivory treasures coming to Norway

Western Greenland a major source

“The likelihood is that the whole of Eurasian demand during the Middle Ages was heavily focused on Western Greenland,” Barrett said on the podcast. “That was quite a shock, because the assumption understandably in the past was that Eastern European finds of walrus ivory were probably coming from places like the White Sea and the Barents Sea.”

Greenlanders were caught up in quite complicated market dynamics, in what was a global commodity.

There were walruses in Iceland, once. But ancient DNA helped another team of researchers see that the Icelandic walrus population disappeared not long after the Vikings had arrived there in about 870 AD.

And the disappearance of walrus from Iceland was surely a factor in encouraging Vikings to head west to Greenland, Barrett said.

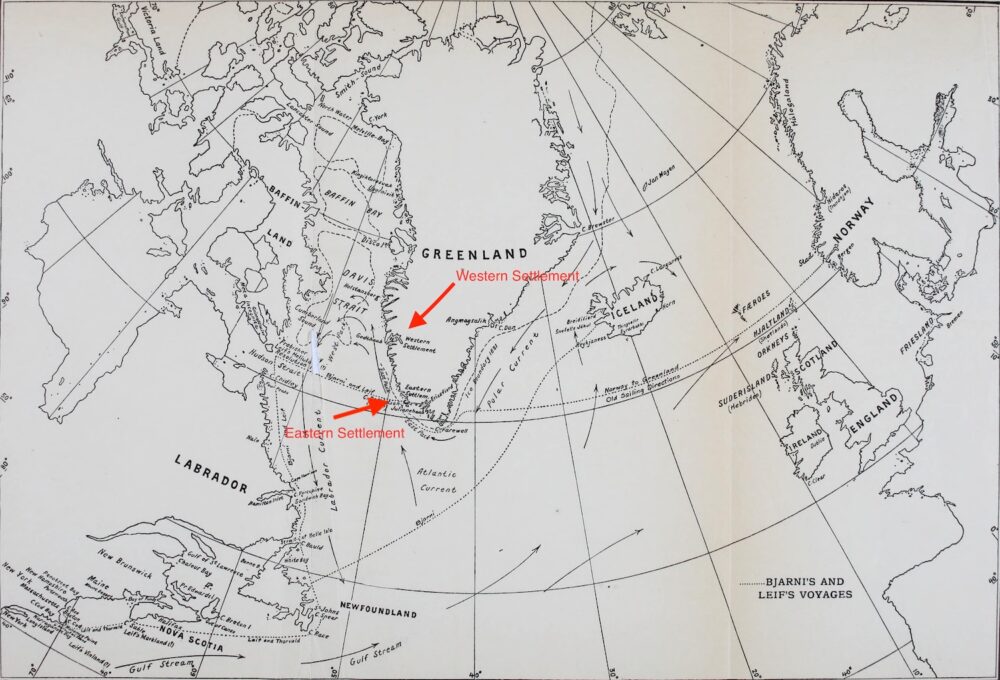

This map from 1914 shows the Eastern and Western Settlements in Greenland, along with assumed sailing routes from Norway to Iceland and Greenland. Note that they do not include a route from Trondheim, although that is known to be a major city in the walrus tusk trade. Image: Internet Archive Book Images – https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14762942631/

“When the Vikings settled in Iceland, the walruses there disappeared very quickly. So they probably were over-hunted in Iceland. And that would be one of several variables that led to the settlement from Iceland of Greenland in the late 900s,” he said.

More importantly, however, it likely played major part in why they abandoned those settlements nearly 500 years later.

- You might also like: Old Norse settlers traded walrus ivory with Kyiv

Farthest north to Inuit trade

As part of their research, the researchers looked at the sizes and characteristics of walrus skulls from this period. They also had information from analysing the ancient DNA.

Gradually, they hunted them further and further north, and then they reached the farthest north one can go. In fact, then they also began to trade for them with the Inuit.

“Through time the walruses were getting smaller through the Middle Ages. In addition to that, they were of a genetic subgroup which was more common in the very far north, rather than more southerly areas in Western Greenland,” Barrett said.

“So the hypothesis is that the Norse were hunting the walruses and demand in Europe was very high, of course,” he said. “And then gradually, they hunted them further and further north, and then they reached the farthest north one can go. In fact, they also began to trade for them with the Inuit.”

Barrett said in the 1200s and 1300s, medieval Scandinavian artefacts begin to show up in Inuit sites in the very far north of Northwestern Greenland and Ellesmere Island.

Hvalsey Church, an important ruin found in the Eastern Norse settlement of Greenland. This church was the location of the last written record from the Greenlandic Norse, a wedding in September 1408. Photo: Number 57 at English Wikipedia, CC0 1.0

“So putting it all together through time, they’re having to harvest smaller and you’re having to go farther north. And if you’re living in southwestern Greenland and you have to row or sail, and it’s a short season, then this is not a trivial issue. Eventually, the journey just became too long to be realistic,” he said.

And that is likely one of the reasons why Greenland’s Western Settlement was abandoned in the 1300s, he said.

- You might also like: What medieval skeletons can tell us about modern day pandemics

Church taxes and elephant ivory

Why did the Norse Greenlanders want to trade with Europe in the first place? It was a long and perilous journey, so the incentives had to be pretty powerful.

There were economic transactions, including the payment of church tax, from the bishopric in Greenland to Trondheim. And that was paid in very large measure, in these early years, in walrus tusks.

Barrett said it’s likely that the settlers just wanted to maintain contact with Europe. But there was a second reason– religion.

This spectacular Crozier head with King Olaf and a bishop made from walrus ivory is on loan to the NTNU University Museum from the Victoria & Albert Museum. It’s part of an exhibition called “Sea Ivories,” which runs through the end of this year. Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

“A bishopric was established in Greenland in the early 1100s. And in 1153, an archbishopric was established here in Trondheim, in Nidaros, with the Greenland bishopric being part of that church province,” he said. “There were economic transactions, including the payment of church tax, from the bishopric in Greenland to Trondheim. And that was paid in very large measure, in these early years, in walrus tusks.”

Two trends would eventually sound the death knell for the walrus tusk trade, however.

The first was the arrival of elephant ivory to Europe in the mid-1200s. The second is a shift in artistic styles, from the Romanesque to the Gothic style, and the way ivory carvers worked their craft.

Elephant tusks were bigger and longer than those from walruses. That allowed for the Gothic style of religious carving, which tended to be more intricate and naturalistic, than the Romanesque style.

Harvest intensified

And yet, Barrett said, their research showed that the harvest of walrus tusks only intensified after the arrival of elephant ivory and the subsequent drop in value of walrus tusks. This seemed counterintuitive – at first.

“It does make sense, because if you’re in Greenland, you want to maintain your contact with Europe. And if the price per tusk has decreased, then rather than hunting fewer walruses, one actually has to hunt more walruses,” he said on the podcast. “And so we see that the Greenlanders were caught up in quite complicated market dynamics, in what was a global commodity.”

A look to the future

Now, Barrett and his colleagues have expanded their research on walruses and other marine creatures with an EU-funded project called 4-Oceans.

Researchers from across Norway and Europe are looking at a range of marine creatures, from cod to otters to whales – and yes, walruses – to understand their economic and social importance over the last 2000 years. They’re also using high-tech tools to make predictions about how a changing climate will affect these and other marine animals.

The walrus research from the 4–Oceans project is also featured in an exhibition at the NTNU University Museum in Trondheim called “Sea Ivories,” which runs until the end of this year.

To hear the full story, listen to the latest episode of 63 Degrees North.

References:

Barrett, James; Boessenkool, Sanne; Kneale, Catherine; O’Connell, Tamsin C; Star, Bastiaan. (2020) Ecological globalisation, serial depletion and the medieval trade of walrus rostra. Quaternary Science Reviews

Barrett, James; Khamaiko, Natalia; Ferrari, Giada; Cuevas, Angelica; Kneale, Catherine; Hufthammer, Anne Karin. (2022) Walruses on the Dnieper: new evidence for the intercontinental trade of Greenlandic ivory in the Middle Ages. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences

Keighley, X et al.Disappearance of Icelandic Walruses Coincided with Norse Settlement, Molecular Biology and Evolution, 36:12, Dec.2019, p2656–2667, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz196