THE TREE OF KNOWLEDGE

A pine took root in the early Iron Age and was felled towards the end of the Viking Period. Last year archaeologists rediscovered it – the stuff that an archaeologist’s dreams are made of.

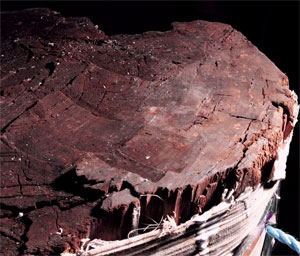

In a freezing cold room on an old wharf in Trondheim, a group of five scientists have gathered around three dark brown logs. Each log is just under a metre tall, and a half-metre in diameter, with growth rings – about to be covered in white silicon –as dense as the grooves in an old vinyl record album.

A couple of months earlier,while most people were busy doing their Christmas shopping, these very logs were being carefully lifted out of the ground opposite the Nidaros Cathedral. Two of them were ferried by wheelbarrow, while the third log was so delicate it was put on a stretcher and carried three hundred metres over to the wharf at 29 Kjøpmannsgata, which houses the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

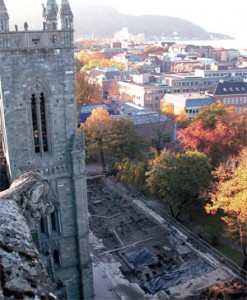

Last autumn, the temporary workshops outside the Nidaros Cathedral were torn down in order to make room for a new visitors’ centre. Archaeologists were granted a few short months during which to prise whatever secrets they could from the ground. The logs were their final and least expected find: After removing 400 graves from the 1700-1800s, a thick layer of soapstone tiles from church construction during the High Middle Ages, and a surprising layer of log houses and fireplaces from the 1100s, the archaeologists expected to encounter “sterile soil”. “Sterile soil” is a layer untouched by human hands – suggesting that it is time to start packing up the equipment. But there, four feet below today’s ground level, awaited yet another bonus discovery for the excavation crew: the remains of three very thick upright logs, bearing testimony to the location of a pre-12th century building of considerable size on this very spot. This was a rare treat, even for Trondheim archaeologists,who frequently come across remnants of medieval Nidaros.

In the autumn of 2004 archaeologists find traces of a sizeable building from the 1100s northwest of the Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. Could they be evidence of a royal estate?

Photo: Unn Yilmaz/NIKU

A GLIMPSE OF THE KING’S ESTATE?

The solid pine pillars with their dense, hard wood did not constitute the only find in this layer: In addition to several large pillar holes, the archaeologists came across shards from a black, glazed bowl, and two Byzantine amphorae. Rare finds, they are evidence of contact with the Mediterranean region.

According to Snorri Sturlason’s Heimskringla, Harold Hardrada (1015-1066) travelled to Miklagard – today’s Istanbul – after fighting in the Battle of Stiklestad. Sturlason further reports that Hardrada, after having ascended to the throne in 1047, built a new royal estate somewhat south of the existing town. Historians have traditionally designated the plateau called Domkirkeplatået, northeast of the cathedral, as the location of Hardrada’s royal estate. To date, however, no physical trace of the estate has ever been found. Could these logs be tied to Hardrada’s long sought-after estate?

Excavation leader Chris McLees at NIKU mulled the idea. The sheer size of the log pillars, as well as the two rows of pillar holes five metres apart, indicated a building that would have towered above most others – perhaps even a building forming part of a royal estate.

A different possibility is that the pillars belonged to Nidarnes farm, which, according to the saga, was located at the Nidarnes headland from the late 900s. No written records describe the farm buildings; however, archaeological remains of buildings, fences, wells and artefacts found on several locations around and underneath the cathedral bear witness to its existence. A stone’s throw away from the pillar finds, at the west front square, earlier archaeological excavations had uncovered the remains of buildings and a fence, C-14 dated back to the 900s. The remains of a barn from the same period have been found in the ground beside the Archbishop’s Palace, another couple of stone’s throws further afield. Perhaps all of these finds came from the Nidarnes farm?

The archaeologists have but a few pieces of what constitutes a big jigsaw puzzle. A growth ring analysis of the pillar finds would provide the past-life detectives with one more piece.

Whatever their origin, the logs did not serve as pillars for long. Sometime in the 1100s, new buildings were constructed. The old building was torn down, and the pillars, stuck fast in the soil, were probably cut off at ground level. Ever since, the pillar remains had attracted little attention – up until this cold Tuesday in February.

DENDROCHRONOLOGY

The growth rings of a tree vary in width according to the temperatures during the summer in which the rings were formed. By comparing growth rings in timber from the same climactic zone, dendrochronologists can determine an average curve for the growth season. Then the average curves from different time periods are overlapped, yielding a longitudinal reference chronology – through which the scientists can often establish when a tree started growing, and when it was felled.

The reference chronology for pine trees from Trøndelag extends all the way back to AD 551. The corresponding chronology starts with AD 1351, since spruce was not used as building material before this date.

Terje Thun at NTNU is an important specialist in the field, and has dated over 1,000 samples from archaeological excavations, plus some 600 log houses and a few stave churches. There is a great need for such dating. He therefore wants to establish a national centre of expertise in dendrochronology – and to colocate it with the C-14 laboratory at NTNU/The Museum of Natural History and Archaeology.

LOOKING AT THE PAST

DENDROCHRONOLOGY

The growth rings of a tree vary in width according to the temperatures during the summer in which the rings were formed. By comparing growth rings in timber from the same climactic zone, dendrochronologists can determine an average curve for the growth season. Then the average curves from different time periods are overlapped, yielding a longitudinal reference chronology – through which the scientists can often establish when a tree started growing, and when it was felled.

The reference chronology for pine trees from Trøndelag extends all the way back to AD 551. The corresponding chronology starts with AD 1351, since spruce was not used as building material before this date.

Terje Thun at NTNU is an important specialist in the field, and has dated over 1,000 samples from archaeological excavations, plus some 600 log houses and a few stave churches. There is a great need for such dating. He therefore wants to establish a national centre of expertise in dendrochronology – and to colocate it with the C-14 laboratory at NTNU/The Museum of Natural History and Archaeology.

Science – as represented by an archaeologist, two dendrochronologists, a curator, and a building technology research fellow– is densely gathered around the old pieces of log. A 500-watt construction work lamp casts its light on the artefacts, radiating a little heat. The focus of interest is on the bottoms of the log. Before the log pillars were set into the ground, their bottoms were carved flat. Therefore, the logs are now upside down, each in its own cropped, green dustbin, with sand filling the space in between the log and the plastic walls of the bin, so that the logs will not shift.

Thoughts and questions, lines of reasoning, and comments fill the air. How far did they have to go to find pine trees this big, with their diameter half a metre? What did the forest look like? What sort of terrain did the trees grow in? What sort of qualities did people look for in the timber? Were the trees felled by the same person, and by using the same equipment? How did they transport the logs from the place where they were felled? The concern today is not whether or not the pillars are from the royal estate. Instead, the scientists are eager to glean as many secrets as possible from the ancient timber about the craftsmanship used to fell, transport and shape them. Moreover, can a growth ring analysis successfully date the logs?

NTNU dendrochronologist Terje Thun produces a piece of chalk and carefully draws a few thin lines across some of the growth rings. This will allow the differences between the rings to emerge more clearly – if it works. But it doesn’t: the wood is too rotten. Perhaps a recently developed photographic technique will provide the adequate tool? Thun discusses the possibility with Kjersti Føllesdal, who has just finished her Master’s thesis on the technique. If applicable, the technique will save them from having to ruin the remains of the pillars by drilling for samples or by cutting off slices of the wood.

As the room warms up, enthusiasm is on the rise, too. Someone moves the work lamp closer to the logs in order to see them better. Immediately, they start to steam. Jørgen Fastner, curator at the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, NTNU, sounds a note of caution: The room should not get too warm. In order for the logs – potentially a thousand years old – to be preserved for posterity, they need to dry slowly. The sand around the logs helps extract the water from them. It was Fastner’s idea to put the pillar stumps into amputated dustbins. The municipal refuse company was able to spare a few bins that had minor faults and that were originally intended for shipment to Russia. Fastner is often likened to Disney’s Gyro Gearloose character by his colleagues.

The pine log – which is half-a-metre in diameter – is in bad condition, and must leave the site where it was unearthed on a stretcher.

Photo: Bruce Simpson

PIECED TOGETHER

Archaeologist and research fellow Harald Høgseth from Sør-Trøndelag University College, and archaeologist Ian Reed from NIKU are about to engage in a small experiment they don’t quite dare believe will succeed. The log in the worst state of decay is far from intact, with several chunks, large and small, scattered about in the sand surrounding it. If there is to be any hope of dating this log, and of interpreting its tool marks, it needs to be pieced together. Fastner produces a gauze roll. One man holds the largest chunks in place while another bandages the trunk. Several pieces are fitted into place through trial and error, and finally, the last, half rotten chip is pushed into the single remaining cavity in the log.

– Gosh, it turned out great! exclaims Fastner in his Danish mother tongue, almost untainted by his many years spent in Trondheim, Norway.

The log no longer looks like an archaeological object: It has regained its shape from olden days. It still has a grey sheen of clay that needs to be removed. The researchers think gratefully about the clay: Without it, the logs would have long dissolved. Two of the scientists go over the log gently with what looks like pastry brushes. A third one pours water over it. After half an hour it is as clean as it was before it was planted in the ground.

The log has now been restored to a single piece and has been rid of distractions from the clay. The growth rings are almost perfectly even, and they are extremely close. We are told that the tree must have grown amidst dense vegetation, perhaps on land facing north, but most likely not on an incline – in which case it would displayed different growth patterns on opposite sides of the trunk. Broad earlywood zones indicate that the log in front of us is from the bottom part of the tree. How far from Nidarnes would one have had to go to find such a whopper of a tree? The Selbu area? Hardly that far. Biologist and dendrochronologist Terje Thun prefers not to make any guesses, but – Singsaker, perhaps. Or Byåsen.

Before silicone casting and growth ring analysis can take place, the log has to be gently rid of its clay deposits.

Photo: Nina Tveter

Harald Høgseth is fully qualified both as an archaeologist and a carpenter. His eyes are fixed on the log. He sees clear marks from the axe that was brought down on it long ago: The marks show that the edge was some 12 centimetres wide.

– And this was probably the approximate direction of the axe blade as it hit the log, he says, swinging his body and the invisible axe towards the axe marks with motions reminiscent of tai chi. He repeats the movement several times. Then he explains that artisans in the past possessed enormous knowledge about the materials they used:

– They knew precisely which qualities of wood were suited for use as floorboards or as wall logs. Therefore, the timber’s appearance and the location where it grew were important factors in choosing the right material.

Høgseth, who comes from Nordmøre (the region around Kristiansund), knows better than most what he is talking about. His Master’s thesis addressed material choice in medieval buildings. For his source material, he used objects from the 1970s excavations of the library plot in Trondheim. Now he is a doctoral research fellow in building preservation at Sør- Trøndelag University College in the Programme for Building Engineering – and the log in front of us is about to become yet another case study, feeding his continued pursuit of the secrets of ancient craftsmanship.

WHITE COVERING THE DARK

Both of the logs have been cleaned. Curator Fastner is making a silicone mass. It will be applied to the pillars in order to make casts to allow Høgseth to study the logs in more detail. Fastner mixes silicon, hardener, and thickening agent, using five per cent hardener, and the right amount of thickening agent needed to achieve the desired stickiness.

Suddenly, Fastner turns and faces the logs: The mass has acquired just the right thickness. He lathers it on the top of the log – which in actual fact is the bottom – and soon covers it completely. The white frosting hardens quickly, but runs somewhat nonetheless – giving the dark brown log, with its covering of white “icing”, the appearance of a cake.

Traces left by tools are to be preserved for posterity as imprints on silicone casts.

Photo: Nina Tveter

Another log is given the same treatment, and then it is time for the logs to rest for a couple of days.

A SERVING OF KNOWLEDGE

A week later we again enter 29 Kjøpmannsgata, stepping across the spot where earlier excavations have produced a rune stick bearing the inscription “Kliba, daughter of the priest, serves you drink”. An alehouse was probably located here, a few hundred years after the sturdy log pillars were placed in the ground on the Cathedral plateau. Today, the log enthusiasts are hoping for a serving of new knowledge.

Since our last visit, Fastner has been back once on his own to see the logs. A layer of plaster needed to be applied after the silicon had solidified. This was necessary in order to ensure that the silicone cast would retain its shape with the imprint intact rather than collapse into a flat mass. A couple of guests call on the log party today: Excavation leader Chris McLees, and Høgseth’s supervisor, professor Lise Bender Jørgensen, show up, full of curiosity.

A few raps and knocks, careful at first, then with slightly more force – and the stiff layer of plaster comes off. The silicone cast is next: A cut is made at the edge with a trimming knife –which goes into the wood. Jokes are made about how future archaeologists will be wondering whatever kind of ancient tool made this extremely narrow mark.

Fastner has made silicone casts on wet, archaeological wood before, but never with the same purpose as now, or on such large pieces of wood. He is awaiting the result with anticipation. Bubbles may have formed. He bends back the silicone mask like the lid on a food tin. Everyone holds their breath – No bubbles. That worked out well, says the curator happily.

– Jolly good fun, grins Høgseth. The silicone cast means a lot to him. Timber from earlier excavations has only been preserved to a very limited extent – through moderate documentation and descriptions filed in the archaeologists’ reports. It has never occurred to anyone that an archaeologist specialising in tool marks might want to know more about old timber. In the future, any find of medieval timber displaying cuts and marks is unlikely to escape silicon casting.

Curator Jørgen Fastner and research fellow Harald Høgseth are busy studying axe marks in the silicone casts.

Photo: Nina Tveter

IMPRINTS OF MARKS

Both of the white casts are lying face up on the table. Fastner is swinging his brush again. This time he is applying a layer of dry, grey powdered clay to bring out the contrasts. In a little while he will have conjured up rings and marks more clearly from the casts. It will take the carpenter quite some time to interpret all the marks that have emerged from the cast by the time Fastner is done. Nonetheless, we are given a few quick samples of what Høgseth will be able to make of the logs. He has spotted some minute marks on the imprints:

– The axe cuts display traces of different wear on the edge. At least two different axes were used to process the logs. And it is likely that two different artisans did the job.

Høgseth is able to read the latter from the direction and depth of the cuts. When he has had the time to study the marks more closely, he hopes to know more about the angle of the axe blade shortly after its entry into the wood, along with the force and the “personality” applied – the manner in which the axe has been swung. He sees the marks as “fingerprints” – and is shortly join a real detective agency, the National Criminal Investigation Service (NCIS), as a visiting student. The NCIS possesses a good deal of knowledge about interpreting the hand movements of murderers – knowledge that Høgseth hopes to find applicable to the dating of archaeological material.

While the timber expert is studying the white silicone disks, the dendrochronologists are preparing to photograph the logs’ growth rings.

GETTING AN ANSWER

In a few months’ time, when the archaeologists have analysed all the artefacts and tests, and have made comparisons of all the drawings of the different layers that were excavated, they will finally be able to draw some conclusions as to what type of building they have found.

Photo: Nina Tveter

The dating of wood by studying growth patterns in annual rings is called dendrochronology. Norway’s expertise in this field is found at NTNU – and on this particular day, it is found in this cool room on a wharf on Kjøpmannsgata – an indication that we are dealing with a field that has a rather small circle of specialists. The new photographic technique they have developed is pure magic. The logs in front of us are not sturdy enough to be put through the conventional test procedures without being completely damaged. With the right lighting and a sufficient number of consecutive growth rings, there is hope of extracting information as to which year the logs were felled. Thun wants to cool expectations, however, because the material is not of the best quality. Føllesdal rigs the lights. With the help of pieces of sticky tape, pins, and film quality suited to big enlargements, she gets her exposures.

The day is over at 29 Kjøpmannsgata. The growth ring experts are hoping to be able to date the two photographed logs within the space of two days.

GUARDING ITS SECRET

The logs have succeeded in guarding the secret of their true age: The dendochronologists did not find what they were hoping for. Another round of exposures is needed. The films then have to be processed, and several days pass.

Thun phones project leader Reed and explains that the material is extremely difficult to interpret. They need more time. Reed has many years’ experience in the field, and has learned not to hope or expect too much before sufficient data is available. Nonetheless, his tone of voice changes slightly. There are few pieces available that can help solve the puzzle on the Cathedral plateau – another one would constitute a more than welcome addition, making it easier to interpret the other finds from the same layers of soil.

A LONG LIFE

The answer is ready — at least almost. Thun and Føllesdal have managed to glean some information from one of the logs – the most delicate one, the one that had to be carried in pieces on a stretcher before it was patched together: The pine started its life in AD 556, and the experts have managed to match the growth rings up to AD 965.

The exact year it was felled will remain a secret, however, as the artisans cut away the outer growth rings. Just how many of them, we will never know, but perhaps 40 years’ worth – or about 1.5 centimetres, accumulated at an estimated growth rate of less than 0.4 millimetres a year towards the end of the tree’s life. No wonder it attracted attention as potential material for a distinguished building some time in the 11th century.

A building belonging to the royal estate, perhaps?

| A pine seed puts down roots somewhere near the Nidarnes headland. Norway is ruled by chieftains, and people believe in Norse gods. In Europe the Age of Migration is coming to an end. In 14 years’ time the founder of Islam, Mohammed, will be born in Mecca. | A 450-year-old pine tree is felled somewhere in the vicinity of the Nidarnes headland, to be used in a large building. Nidaros is probably ruled by Olav Tryggvasson or the Earls of Lade. Christianity has gained a good foothold in Norway. In China, sciences such as mathematics and medicine are pursued. | The large building at Nidarneset is pulled down, and a new building is built on top of the remains of the old log pillars. Its next door neighbour is the Christ Church, erected by Olav Kyrre. The Crusaders are making their way through Europe, determined to win back the Holy Land from the Muslims. | The temporary workshops opposite the Nidaros Cathedral are pulled down to make room for a new visitors centre. The archaeologists have a few months’ time to sift through the ground. When they believe they have reached “sterile soil”, three old pine pillars emerge. | Through growth ring analysis, the scientists find that one of the logs started its life an impressive 1,449 years ago. |

By Nina Tveter