Norwegian journey, Vietnamese dreams

The Vietnamese are among the most successful of all non-western immigrants to Norway. Why?

It was a cold autumn day just over 30 years ago when the first plane load of Vietnamese boat refugees touched down in Værnes airport in central Norway. There were twenty of them, children, parents, some single young people – all in thin cotton clothes, and with almost no luggage.

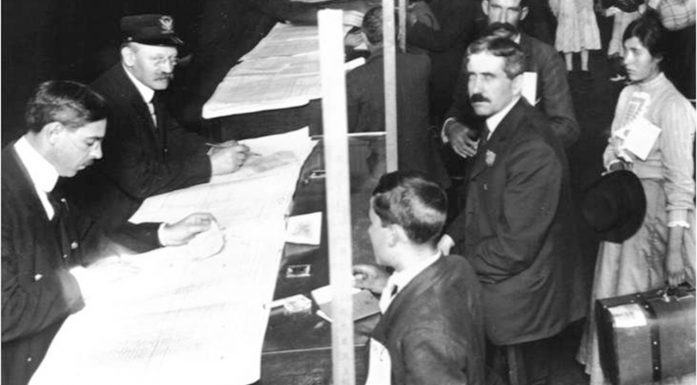

Photo: Thor Nielsen

– Mom and Dad work for us!

“Ideally, my parents would want me to be an engineer.”

So says Vu Lâm, from the small coastal town of Haugesund. Lâm came to Norway in 1985, when he was four months old, and is the son of parents who had college educations from their homeland. Vu is studying Industrial Economics and Technology Management at NTNU, and is thus fulfilling his mother and father’s wishes.

“It would have been fine if I had done something else too, but they were clear that I at least had to get a bachelor’s degree,” he says.

Vu said that Vietnamese parents are very concerned that their children pursue higher education. “They work hard and do everything to ensure that we will get an education. For example, my parents never wanted me to take a part-time job. I was supposed to concentrate on school and studies, while they took care of finances.”

Lise Vy Quyên Vu is studying bioengineering at Sør-Trøndelag University College. Her parents belong to the first group of boat refugees who arrived in Trondheim in 1979. Both took high school degrees and pursued vocational education here.

Lise has the same impression as Vu: “Some parents perhaps push a little too hard. But they are very concerned that we take advantages of the opportunities that are found here, and that we have a brighter future than they themselves had.”

Lise and Vu are respectively chair and deputy chair of the Vietnamese Student Association in Trondheim. It was created many years ago, when the first Vietnamese students didn’t speak much Norwegian and had fewer Norwegian friends. Now Vietnamese youth spend more and more time with Norwegians, but the association still has a social function and is a place where students can take care of their “Vietnamese” side.

“My parents are very happy that I am in the association. I also think that there are advantages keeping a foot in the Vietnamese traditions,” says Lise. For example, the Vietnamese who spend the most time with their Norwegian friends begin to lose their Vietnamese language skills.

“But if you compare young Vietnamese in Norway to Vietnamese in other countries, the Norwegians are much better,” says Vu.

A few weeks later another plane arrived, this time with about sixty refugees on board. Over the course of just a few years, roughly 500 Vietnamese boat refugees found a new home in Trondheim – a city which at the time had around 130 000 inhabitants.

It was hardly Norway and its winter cold that they had in mind as their future homeland when they set out on the open sea in their tiny boats. But it was to Trondheim that they came, and it is in Trondheim where they have remained. Today, roughly 900 people of Vietnamese background call Trondheim home. In Norway, that number is nearly 20 000.

And if we believe the statistics, the Vietnamese are among the most successful in adjusting to their new homeland of any of immigrants with a non-western background. That is true both in Trondheim and elsewhere in Norway.

What kind of immigration intake must they have experienced at the time, which clearly did something right?

Or perhaps we should rather ask: What have the Vietnamese themselves done?

Exceptionally flexible

Among those who waited in the arrival hall on that October day in 1979 was a young social worker named Berit Berg. Her total work experience at the time was comprised of fourteen days working at the Norwegian Refugee Council’s newly established office in Trondheim.

That’s not much in a district with 260 000 inhabitants. And the numbers are getting better year by year. “It’s not often that we see Vietnamese names on our list nowadays. Last year there was just one,” says Sem.

The police chief confirms that when they do break the law, the Vietnamese are largely involved in drug and property crimes. They are virtually never involved in violence. “We have had two cases of assault and battery in almost seven years, and I can’t think of a single case of gang fighting in this town,” he says.

Ove Sem would rather not speculate on an overarching explanatory model, but believes this pattern can be connected to at least three factors:

“First, many of them are Buddhists, which is a peaceful religion. Second, they are almost never in the places where it there is violence. They don’t tend to drive the downtown streets on Saturday and Sunday nights, as other groups do. And third, it is my impression that they are better integrated than other non-western immigrants. The same applies to the Chinese, Indians and Sri Lankans; we almost never have problems with them either.”

Forever VietnameseVietnamese in Norway

- Two-thirds are first-generation immigrants. Most arrived as boat refugees or came as a part of family reunification in the 1980s. Nine out of ten have Norwegian citizenship.

- Two-thirds are first-generation immigrants. Most arrived as boat refugees or came as a part of family reunification in the 1980s. Nine out of ten have Norwegian citizenship.

- The education level in the first generation is very low. But 47 per cent of the second generation has pursued higher education – compared to 31 per cent in the Norwegian population as a whole.

- Employment and income levels are high compared to other immigrant groups that have lived in Norway for many years, but are still lower than Norwegian levels. A majority own their own home.

Vietnamese in Norway

- Two-thirds are first-generation immigrants. Most arrived as boat refugees or came as a part of family reunification in the 1980s. Nine out of ten have Norwegian citizenship.

- Two-thirds are first-generation immigrants. Most arrived as boat refugees or came as a part of family reunification in the 1980s. Nine out of ten have Norwegian citizenship.

- The education level in the first generation is very low. But 47 per cent of the second generation has pursued higher education – compared to 31 per cent in the Norwegian population as a whole.

- Employment and income levels are high compared to other immigrant groups that have lived in Norway for many years, but are still lower than Norwegian levels. A majority own their own home.

Even though the Vietnamese call Norway “home” and are unusually well-integrated, they are and will always be Vietnamese.

“It’s all about mindset and attitude,” says Berg. “My informants say that when it comes to things like closeness, intimacy and sharing concerns, they prefer their own people – as we do. And they usually marry within their own culture. But otherwise, they say they have the best of both cultures. Welfare, equality and openness from us, courtesy and respect from their own culture. But they believe that Norwegians have a rather simplistic view of them.”

And of course, the story of the Vietnamese in Norway is not just sweetness and light, Berg is quick to point out.

“I have experienced scepticism on the part of Norwegians. I have seen limited and poorly organized educational offers in the Vietnamese language. And we have not yet been willing to give the first generation of immigrants jobs, or teach them Norwegian.”

A two-way street

Among the immigrant groups that have the most difficult time in modern Norway are the Somalians. Their educational and employment levels are low, and their problems are similarly large.

“But they’ve only been here a short time, and the Vietnamese have been here a long time. It will be interesting to see what this looks like about 15 years,” says Berg.

If you ask Berg to summarize the three most important actions we can take to promote integration, she will answer:“We must work with the attitudes of youngsters in schools and kindergartens. We are good at saying that integration is a two-way street, but in practice we put the entire burden on one party. We must provide language training and enable immigrants to have access to education, including those who came before the current welcoming programme.

And we need to give refugees and asylum seekers as strong a start as possible. To put a young, single man in a studio apartment block with 50 other young men of different nationalities is not a very good idea. Housing is an important avenue for integration, and this is a place where the authorities can do something.”

“It is important to practice what we preach,” Berg adds. “And we have to be bold enough to confront the issues. Today we leave the debate over immigration to political parties that are hostile to the issue. If you ask me if integration in Norway is unsuccessful, I will answer no. But there are problem areas and black holes that we have to look at. But the job shouldn’t just fall to minorites, the responsibility belong to us all.”

“We had a budget, some apartments, plenty of idealism and a lot of good will. But otherwise we didn’t have a clue,” she admits.

Today, Berg works as division head at NTNU Social Research AS, Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. And after 30 years of working with refugees and immigrants, she is totally clued in.

“Seen through Norwegian eyes, we may well call the Vietnamese in Trondheim a success. But it’s not a lot about what we did. The reasons are definitely because of the Vietnamese themselves. They have been remarkably flexible and adaptable. They wanted to be integrated. They were determined to be part of ‘the Norwegian dream’. And perhaps they have been more willing than other immigrant groups to work with whatever they got, and accept the situation as it was.

But if we see the process as an interaction, it is obvious that their inviting, non-confrontational manner, and their willingness to work has also suited us Norwegians very well,” the researcher says.

Home is Norway

In May 2009, Berit Berg and Kirsten Lauritsen (senior lecturer at Nord-Trøndelag University College) published the book “Exile and Life Cycles”. The book includes interviews of refugees who came to Norway from Chile, Vietnam, Iran and Somalia from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. Berg and Lauritsen have also talked with the second generation, those who arrived as infants, or who were born here.

“We have not yet been willing to give the first generation of immigrants jobs, or teach them Norwegian.”

Berit Berg, NTNU Social Research

The survey confirms that the Vietnamese stand out from other nationalities in a number of areas, including in considering Norway as their “home”. Vietnam is certainly their “homeland” – they miss it, and they might go on holiday there. But they will never return. Home is here in Norway.

“That’s partly because they have been here a long time. But it’s also because they realized early on that they probably never could return. That kind of recognition provides a completely different motivation for integration,” says Berg.

“The Chileans, for example, who arrived at about the same time, had a much stronger idea that their exile was temporary at best. They would soon return home, they thought, and therefore they didn’t have nearly the same incentive to be integrated.

More than perhaps any other refugee group, the Vietnamese have been determined to establish a life here and make use of the opportunities that are found here. They have met the challenge, rolled up their sleeves, and done the heavy work. Without being broken by the experience, but also without open confrontation.”

But they have also achieved a quiet revolution: No one, including the Norwegians, has children who are so good at school and are so highly educated!

Education Revolution

Of the first 80 boat refugees Berit Berg took in, perhaps two or three had some form of education. Most were fishermen and home workers with an average of five years of primary school. People who immigrated later had more schooling, but the older generation’s education levels were consistently low.

But the situation with their children is remarkably different: Not only do they get some of the best grades of any high school students (just behind of students of Sri Lankan descent), they also are much more likely to pursue higher education than the population as a whole. This is true for both girls and boys.

At first, degrees in status occupations, such as engineering, medicine and law, topped the statistics. Now young Vietnamese chose their degrees based more on their interests and abil- ities, and this second generation is found in all subjects and pursuits offered by Norwegian universities and colleges.

“We have seen inspiration and motivation – and probably also pressure – from parents, which we hardly ever find in other immigrant groups,” says Berg.

“Certainly, education has always had high status in Vietnam. The refugees soon realized the opportunities their children had in Norway. But these parents themselves lacked schooling, Norwegian language skills and any understanding of the Norwegian educational system. Few were able to follow up on their children’s schooling in the way a Norwegian parent might. Nevertheless, they have ensured that their children succeeded, and that requires tremendous effort! It’s particularly gratifying that girls have been so greatly encouraged, too.”

Peaceful criminality

One of the few statistics in which the Vietnamese are distinctly less lucky, are crime statistics. The number of convicts of Vietnamese origin is above the national average and in line with the average for non-western immigrants. Most sentences are for property theft, narcotics or traffic crimes.

On the other hand, there is no group that is as little susceptible to theft, vandalism, violence and intimidation as the Vietnamese.

Police Chief Ove Sem at the Trondheim Police Station is in contact with different immigrant groups, and usually knows who is doing what. He can say with satisfaction that Trondheim’s crime statistics are probably are better than the national statistics:

“Since 2002, in the Sør-Trøndelag Police District we had only 25 convictions of people born in Vietnam,” he says. (One person may have several convictions, which means the actual number of offenders is lower.)