The Black Death bacteria continues to kill

It took almost six months for Egil Lien to get permission from the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the US to study the plague bacteria that, in its time, killed half of Norway’s population. Now, an antibiotic-resistant strain of the bacteria has been found.

As the bacteria responsible for killing a large part of Europe’s population during the Black Death, the plague bacteria Yersinia pestis has a long kill list on its conscience.

Swelling and dark boils

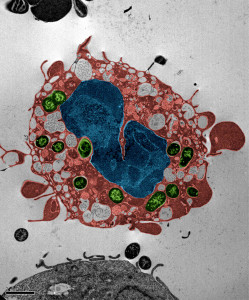

An immune-system cell dies from Yersinia pestis infection. The cell membrane blisters and the cell’s nucleus mutates. Green: Bacteria. Red: Cell contents. Blue: Nucleus. (Weng et al. PNAS 2014, 111:7391)

The mass murderer Yersinia pestis is responsible for three diseases that you definitely do not want to get if you live far from medical help: bubonic plague, pneumonic plague and septicemic plague.

Bubonic plague is often transferred to humans from mice and rats through flea bites. After entering the body, the bacteria is transported to the lymph nodes, causing swelling and darkly coloured boils in the armpits, groin, and neck. Untreated, bubonic plague kills around 50 per cent of its victims.

Pneumonic plague is transmitted directly from person to person through airborne fluid droplets, killing almost 100 per cent of untreated victims in two to three days.

Septicemic plague is a form of blood poisoning most commonly caused by a bite from an infected flea. This allows the bacteria to enter the blood directly and begin to reproduce. Victims die in a matter of days in almost 100 percent of cases if the disease goes untreated.

“The Black Death was most likely a combination of all three forms of plague,” says Egil Lien, professor of medicine at CEMIR, the Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research at NTNU. “Maybe as much as half of Norway’s population was killed.”

Epidemic in a mining town

Today, the bacteria still infects several thousand people every year, mostly in countries such as Madagascar or the Congo. A few years ago, a pneumonic plague epidemic broke out in a mining town in the Congo, killing a large part of the population.

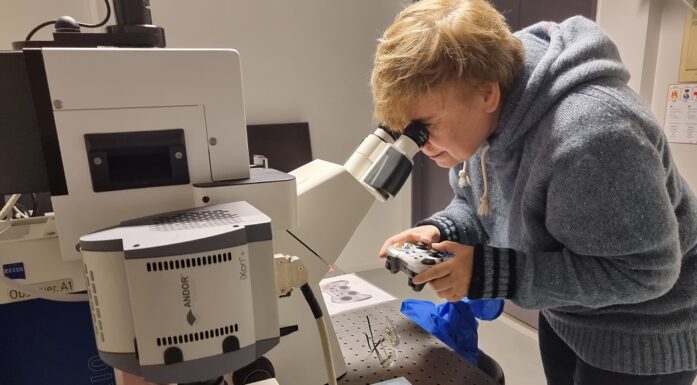

“The bacteria is easily combated with antibiotics, but before we had antibiotics, most people were helpless against the plague,” says Lien (photo).

Now antibiotic-resistant bacteria are on the rise globally.

According to Dag Berild, associate professor at the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Oslo Institute of Clinical Medicine , more people die of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in Europe annually than in traffic accidents. He believes that if the increase in resistance continues, we will soon be living in a world without antibiotics.

“Certain antibiotic-resistant strains of the plague bacteria have been found,” says Lien. “But luckily, they aren’t widespread.”

- You might also like: On the hunt for new antibiotics

Fear of bioterrorism

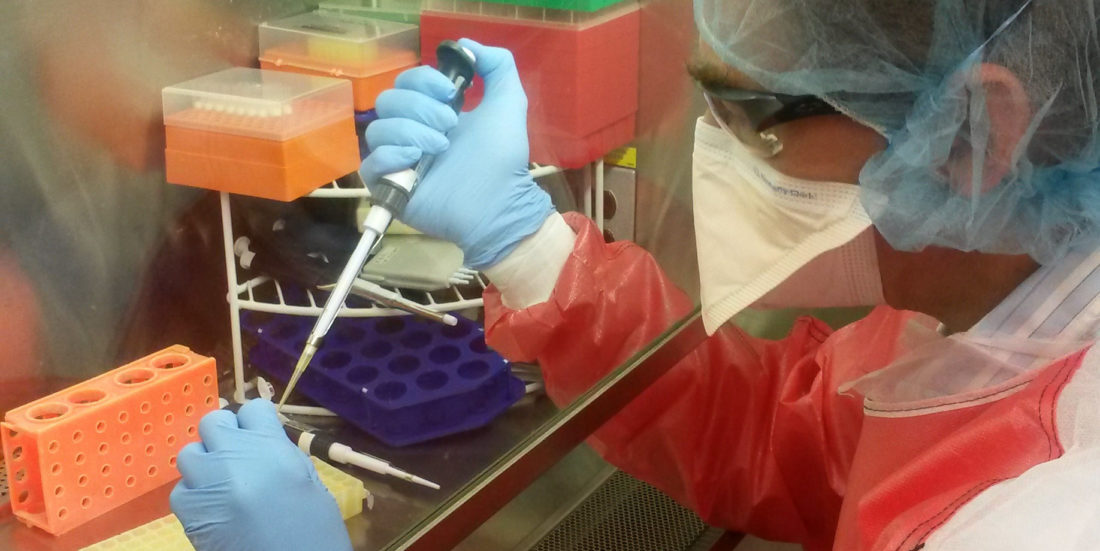

Lien was so interested in studying the mass murderer Yersinia pestis that he went through an almost six-month-long approval process with the the FBI. The fear was that the bacteria would be used for bioterrorism, and in true American fashion, the FBI did their job thoroughly. Lien’s friends were called. Colleagues were contacted. Fingerprints were checked in international databases. Lien was cleared and given access to the highest level security labs at the University of Massachusetts.

In the lab, Lien studies how the bacteria kills. And he has discovered something completely new.

Tricks the body into thinking it is something else

“It has previously been unclear which mechanisms plague bacteria use to kill our cells,” Lien says. “We discovered that the mechanism used to kill immune system cells is the same one that is used to send messages to the immune system.”

Viruses and bacteria each behave in their own special way in the body. Some hide, while others make a scene. The plague bacteria gets straight to work, killing cells that the body uses in the immune system along with many other types of cells. It is also very good at tricking the body into thinking that it is something else by changing its surface.

“We also found that the plague bacteria uses pathways in the body most commonly used by viruses,” Lien says. “We discovered a lack of important proteins in mouse cells that make them much more susceptible to plague infection. This means that medication that stimulates these proteins could be important for developing new treatments, and perhaps better vaccines. Our work gives us new knowledge about basic immune system responses against bacterial infections. An American pharmaceutical company is now interested in our findings.”

The research was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Quotes from Dag Berild, associate professor at the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Oslo Institute of Clinical Medicine are taken from a commentary in Aftenposten.