How do small birds survive the winter?

Mature birds are better at surviving the winter than young birds. Older birds have learned a few tricks along the way.

Norway’s small birds face many challenges during the winter, including short days and long energy-intensive nights, tough weather conditions and food shortages, along with the risk of becoming a meal for hungry predators.

The smallest birds have to use every daylight minute to find food. This photo shows long-tailed tits and one Eurasian blue tit. Photo: Thinkstock

Many of the smallest birds live on the edge of survival with this enormous physical pressure.

Bottleneck period

Northern winters are the limiting factor for many creatures. This is especially true for the smallest birds, which have to use every daylight minute to find food. They are constantly adjusting to shifts in weather and trying to fend off starvation.

Cold temperatures, strong winds and snow-covered branches increase the stress factors for birds that primarily reside in trees. The birds optimize their energy balance by changing location continuously depending on the weather.

Changing sides

In cold, sunny weather, small birds conserve their energy by keeping to the trees’ sunny side. The goldcrest, Norway’s smallest bird at only 5-6 grams, and the slightly larger coniferous tits (coal tit, crested tit, and willow tit) all take advantage of this sun exposure.

Even small changes in wind speed affect birds’ energy balance. Coniferous tits move to the lee side of trees when winds approach moderate breeze level (5-6 m/second), which offers a significant advantage.

Every calorie counts

Small birds need to find enough food to get through the day and also build up adequate fat reserves for the coming night – all in the course of the limited daylight hours.

Long-tailed tits at 8-9 grams and willow tits at 10-12 grams, for example, need to increase their body weight by 10 per cent to survive an 18-19 hour night.

Willow tits can reduce heat loss and conserve energy by lowering their body temperature at night. Photo: Thinkstock

Unlike the willow tit, the somewhat larger great tit does not normally have the ability to lower its body temperature and thereby reduce heat and energy loss, and has to lay on even more body fat.

Dead great tits have been found in birdhouses when nighttime temperatures have dropped to -30°C.

Safest at the top

Survival requires more than just finding food. It’s also a matter of not becoming the next meal for hungry owls or sparrowhawks.

Birds are always gauging whether to hunt for food or to keep an eye out for potential predators. They often congregate in flocks in difficult periods, presumably to take advantage of more pairs of eyes to spot predators.

Birds search for food where they are less likely to be preyed upon. The safest places are in the upper parts of trees.

Mature birds fare the best

Bird flocks have a shared interest in efficient foraging as well as protecting themselves from their enemies. And at the same time they are also competitors.

Since small birds can readily spot a high-flying owl or hawk, predators’ odds for a meal are greatest when attacks happen low to the ground.Photo: Thinkstock

Willow tits live in small multi-age flocks except during the breeding season. On average about 75 per cent of the older birds, versus only about 40 per cent of the young birds, survive the winter. What accounts for this difference?

Mature birds are socially dominant over younger ones and generally have better access to resources such as food and good nighttime roosts.

The older birds also occupy the safest places, with the result that the young birds lead a much more uncertain and stressed existence than older birds do.

Changing with the weather

Young birds maintain a little distance from the dominant older birds in mild weather when the temperature reaches 0°C or warmer, but both groups stay mainly in the upper half of the trees where they are safer from hungry predators.

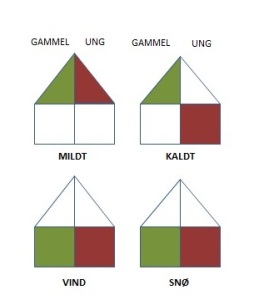

The figure below illustrates how birds distribute themselves in pine trees in different conditions. When conditions are favorable with no wind and mild weather, both the old (green) and young (red) tits keep mostly to the upper reaches.

Tree locations of older and younger birds under varying conditions. Mildt= Mild, Kaldt=Cold, Vind = Wind, Snø= Snow Illustration: NTNU

The birds need to spend more time foraging for food as soon as the temperature drops and their energy requirements increase. They then flock together to reduce their risk of predation and can spend more time feeding.

In these colder conditions the distribution of the birds changes, as the mature birds search for food above where it is safer, and force the young birds to stay in the lower part of the tree.

Snow and wind

When tree branches are snow-laden, both older and younger birds prefer to be in the lower branches where it is easiest to find food.

To avoid heat loss in strong winds, most tits congregate on the lower branches of the trees’ lee side, where the wind penetrates least.

In both of these weather situations, young birds have less time to forage since they need to keep an eye out for the older birds and other predators.

Young birds most vulnerable

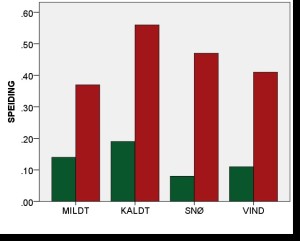

Young birds, especially in cold weather, are forced to be vigilant for both predators and the dominant older birds, which means that young willow tits may spend only about 60 per cent of their time foraging versus 85 per cent for the mature birds.

The birds have to use their days optimally so they can put on a critical amount of fat needed to survive the night.

The figure above shows the average percentage of time being vigilant instead of feeding for dominant older willow tits (green) and younger willow tits (red) under various weather conditions. The mature birds stay where there is least risk of predation so that they can spend more time foraging. The young ones are forced into riskier areas and have to be alert to both greater predation risk and the aggressive older birds. Illustration: NTNU

(Graph labels) y-axis: On guard; x-axis: Mildt=mild, Kaldt=cold, Snø=snow, Vind=wind

Recurring disturbances due to changing weather conditions and dangerous predators give birds less time to build up the fat reserves they need to survive their long nighttime fasts.

The higher mortality rate among young willow tits is due in great part to having less time to find food. As might be expected, more young than old willow tit remains have been found in the regurgitated pellets of Eurasian pygmy owls and northern hawk owls.

Despite young birds losing valuable foraging time when together with their mature species-mates, their company has some positive sides. The young learn the territory from the older birds, and greater bird numbers also warn against predators more effectively.

Every bird must carefully adjust its tactics— all depending on ever-shifting meteorological conditions and its social situation — to increase its chances of surviving one more day or week or month, until the milder days of spring finally arrive.