Two hundred and seventy-eight wind turbines won’t cut it

The transition to green energy hasn’t really begun, according to Associate Professor Espen Moe. Even though the 278 new wind turbines that will be built in central Norway are an important investment, it’s not nearly enough, he says.

GREEN ENERGY REVOLUTION:“The transition to green energy will be the biggest structural change we’ve experienced over the last 50 years in the energy and industry sectors,” says Professor Espen Moe, from NTNU’s Department of Sociology and Political Science.

Wind power and solar power still constitute only 4 per cent of electricity production in the world, and 1.3 per cent of the world’s energy consumption.

As of yet, not too much has happened in this “green transition” that will make our energy mix more environmentally friendly. The term is popular in speeches, but the world isn’t on board with the green transition in the energy sector. At least not yet.

Moe is part of NTNU Sustainability, one of NTNU’s four strategic research areas, where he is head of a research area that looks at institutional frameworks. He has just written two books, which include a discussion of the major changes that will be needed to build a more sustainable society.

Wind power development in isolation

Now 278 wind turbines are to be built in Fosenhalvøya, Hitra and Snillfjord in Trøndelag in Central Norway. Looking at Norway’s wind projects in isolation doesn’t make much sense, Moe believes, but he is still a supporter

Initially Norwegian wind power will have regional economic effects and drive down electricity prices. But as long as wind power remains strictly Norwegian in scope, its climate effects will be minimal.

“Wind power in Norway makes sense if we succeed in expanding the system boundaries from the national to the European,” says Moe. “The point of Norwegian wind power can’t be to produce more electricity for Norway— we already have enough— the point must be to contribute to a renewable electricity system for all of Europe. Only then will wind power lead to reduced greenhouse gas emissions. But the distribution systems to supply the rest of Europe with electricity are still far too underdeveloped.”

The point of Norwegian wind power cannot be to produce more electricity for Norway – which already has enough from hydropower. This view is of the Hundertfossen dam. Photo: Thinkstock

One of the biggest problems is the lack of coordination between wind power development and the upgrading and expansion of power lines and cables, as well as of power lines between different countries. Norway has some power lines to Sweden and cables to Denmark, Germany and the UK, but most countries in Europe have very poor quality transmission lines to neighbouring countries.

In addition, international systems are needed that make it easier not only to transfer power, but to sell it between different countries, so that Norwegian electrical companies actually benefit from creating green power for export.

- You might also like: Norway needs good climate laws

Not enough, but necessary nonetheless

Norway has the best water resources and the best wind resources in Europe, and regardless of the world’s energy conservation measures, we’re going to need more renewable electricity in Europe if we actually want to change from a fossil-fuel-based to a carbon-free energy system, says Moe. Even though this is not Norway’s need, it is a necessary prerequisite for the transition to green energy.

“This isn’t enough in itself,” stresses Moe, because so many other things have to happen.

But without the development of Norwegian wind power, the chances of a transition to green energy are appreciably less than with its development, “even though this development doesn’t make that much sense, from a short term perspective,” Moe says.

So what do we need to do to make the transition?

Baby steps

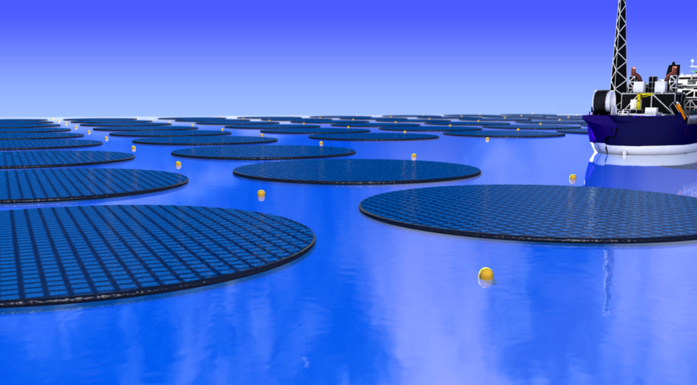

Wind and water and sun are becoming more prevalent as energy sources, but the world’s total energy consumption is also increasing, resulting in no net decrease in the use of fossil fuels such as coal, gas and oil. Illustration: Thinkstock

Some countries have taken what amount to green baby steps, but renewable energy still constitutes only about 11 per cent of world energy consumption. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has projected that this proportion will increase to around 15 per cent by 2040.

The projection includes biofuels and firewood, not just solar, hydro and wind power. This can hardly be seen as a revolution or major shift.

Certainly wind and water and sun are becoming more prevalent as energy sources, but as the world’s total energy consumption increases, fossil fuels like coal, gas and oil have not decreased proportionately.

- You might also like: The Paris summit is over, now what?

Must have power and political will

“The transition to green energy won’t happen by itself,” says Moe.

For a green transition to take place, renewables have to become cost-competitive, and political decisions need to make this happen. At the same time, improving the energy grid to handle enormous quantities of power is critical to be able to cope with contributions from new energy sources.

A green energy shift needs politicians and other people in power who are willing and capable of changing the status quo. And that’s not that easy to accomplish, at least not everywhere.

Germany with its restructuring ability and Denmark with its wind exposure have set their course in this direction. Norway, on the other hand, hasn’t really taken those steps yetwhich raises the question: why is this so easy to achieve in some countries and so difficult in others?

“Countries that are strongly attached to the status quo will be difficult to change,” says Moe.

Norway has been able to avoid emissions reductions by purchasing emission credits from other countries. Photo: Thinkstock

Norway is definitely closely tied to the status quo through its large petroleum industry. With its huge stash of oil money, Norway has been able to buy its way out of emissions reductions by purchasing emission credits from other countries. But these purchases have not led to any appreciable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by Norwegian companies.

- You might also like: What you buy affects the climate

Biggest businesses bristle

All big change encounters opposition from the status quo. Large firms are often linked to established schemes, social structures and regulations.

According to Moe, 9 out of 10 of the world’s largest companies by revenue are based on fossil fuels, either because they are producers of fossil fuels or because they use fossil fuels to manufacture goods.

Oil companies dominate the list of Norway’s largest companies, too. They like to keep a hold on power and have obvious political connections. Laws and regulations are often designed to satisfy the needs of large enterprises. Politicians are generally not eager to get on their bad side, either.

The petroleum industry accounted for 39 per cent of Norway’s total exports in 2015. Oil generated 20 per cent of Norwegian revenue, according to figures from Norway’s National Budget. Despite falling revenues and rising unemployment, oil is without a doubt the country’s largest industry.

With two thirds of entrepreneurs and small businesses going defunct within ten years and few achieving big success, politicians find it far easier to support the powerful oil industry.

As a result, it’s no simple matter to change the basic structures of society in a country like Norway. The challenge is to implement changes that benefit small businesses and provide a real possibility for new sources of energy to compete with the established order.

- You might also like: ABC—Anything but coal

Easier in Germany

Change has happened more smoothly in Germany, which is committed to discontinuing nuclear power plants while investing heavily in renewable energy sources through various schemes. But the German situation is different.

Most Germans would prefer not to be dependent on gas from Russia, for obvious reasons. Coal is a major energy source, but highly polluting. Oil is not a national resource. And although the IPCC—the UN’s climate panel—sees nuclear power as part of the solution, most Germans are sensitive to the potential risks and do not.

“Germany has had social and political consensus around environmental solutions going back several decades. It began with the fight against acid rain, accelerated with the fight against nuclear power following Chernobyl, and gained additional momentum with the ozone layer. The consensus that renewable solutions are both good and necessary crosses party lines,” says Moe.

- You might also like: – Climate—A challenging type of justice

American measures

In the United States, Republicans have a majority in both Congress and the Senate and have stopped any attempts by Barack Obama to introduce greener programs.

Obama has been forced to circumvent the political institutions and has instead introduced changes directly from within the administration.

That means that new green schemes have no real political support, and could be in danger of being reversed later. But these changes have also yielded tangible results, including new energy standards for household appliances, new vehicle emissions standards, a committee to look at carbon capture and storage, big green research projects, and investments in smart grid projects that will create a more efficient power grid.

Obama has found some of his strongest supporters in the US Department of Defense. They may not always care about the environment, but most soldiers most recognize the benefit of not being dependent on energy sources from unstable or politically conflicted areas of the world.

- You might also like: A climate dictionary

Big investments

Moving away from fossil fuels requires large investments, especially in the energy grid. Today’s energy networks aren’t built to cope with highly variable renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

Moving away from fossil fuels requires large investments, especially in the energy grid. At the same time, we continue to pump out oil and gas like there’s no tomorrow.Photo: Thinkstock

The wind doesn’t always blow, and the sun doesn’t shine all the time. We even tend to consume more energy on dark winter evenings than on bright summer days.

At the same time, renewable energy is a perishable commodity with very limited storage capabilities. Hydropower offers one of the few regulatory mechanisms that exist, where you can regulate the water flow from reservoirs. Smart grid technology can help to resolve this issue, but not everything.

In Germany, two million consumers can now sell electricity back to the power companies, because they have installed solar PV panels on their homes. This complicates the picture and has also led to a dramatic drop in energy companies’ profits, because consumers are now simultaneously competitors. It is unrealistic to expect that these energy companies will contribute money to a new electricity grid that reinforces this trend. So this means the government will need to step up.

Les også: Prime-time charging of electric cars could be a problem

Low oil prices

Fracking is a controversial oil extraction method because it is highly polluting, but it is becoming more and more common. Here, protesters in North Carolina, USA make their opinions on fracking known. Photo: Thinkstock

In other words, it will take political will to fund the necessary grid improvements and give renewable energy sources a chance.

Finding this willingness is no easy task, especially in times where oil is so cheap that new sources of energy don’t seem as attractive. New production methods in the United States and political measures in the Middle East have sent oil prices plummeting.

Low oil prices have the greatest effect on investments in renewable energy. Coal is cheap, and coal consumption worldwide last year was the highest it has been since 2007.

“Lower oil prices have more than one side to them,” Moe says.

But while oil is indeed more competitive, companies’ short-term ability to invest in new areas and deposits is reduced. Advantages and disadvantages, depending on which side of the table you’re sitting on.

It has to happen

In Norway, it’s been slow going with energy changes. But Moe expects that this won’t last forever.

We have great opportunities to help stave off the problems facing an energy-hungry world, both now and in the future. Photo: Thinkstock

“Change has to come. It’s absolutely necessary. We can’t continue like today,” he said.

The petroleum industry will not dominate the Norwegian economy—or the global economy—as much in the future. It couldn’t maintain its dominance forever anyway, since the resources are not unlimited.

Norway has a long and windy coastline that is well suited for developing new energy sources and meanwhile, the country already has a lot of hydropower. So the opportunities to help stave off hunger for an energy-hungry world are great. If the will is there.

“The transition to green energy will begin the day we see major structural changes. I don’t know what the world will look like in ten years, but the shift hasn’t happened yet,” Moe concludes.

Moe’s new books:

Renewable Energy Transformation or Fossil Fuel Backlash: Vested Interests in the Political Economy (Energy, Climate and the Environment)

The Political Economy of Renewable Energy and Energy Security: Common Challenges and National Responses in Japan, China and Northern Europe (Energy, Climate and the Environment)