Is the woolly mammoth really gone for good?

Should we reintroduce animal species that have died out? New technology may offer opportunities that no one could imagine a few decades ago. But the answer may not be as simple as you think.

“Some people talk about bringing woolly mammoths back to the Siberian tundra,” says Professor Tom Gilbert.

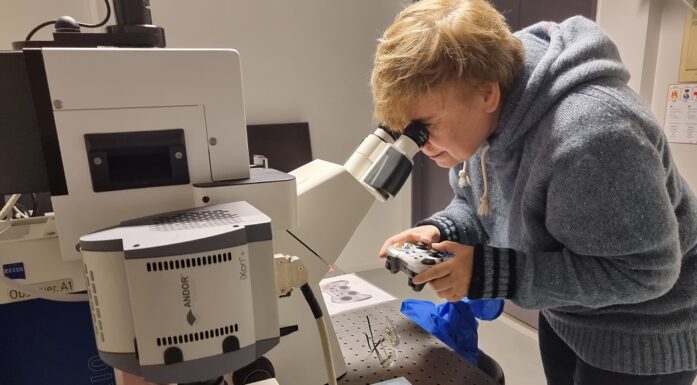

He can most often be found at the University of Copenhagen’s Centre for GeoGenetics, but he also has a part-time position as an adjunct professor at the NTNU University Museum.

New DNA technology makes it more likely than ever that we we’ll soon be able to take genetic material from preserved specimens of dead animals and produce live offspring. Enthusiastic proponents believe we can bring back extinct animal species through a process called de-extinction.

Gilbert is engaged in the field of de-extinction, not necessarily because he unconditionally supports reintroducing extinct species, but because the technology behind the process is so fascinating.

“People want to bring back the mammoths by taking DNA from frozen specimens that have been found. I’m interested in the limitations in the process,” he says.

Several such specimens have been discovered in different places in Russia. These animals have been preserved in the ice for millennia. But is that enough?

Gilbert points out that to recreate a species, you need to have complete cell cultures from these animals. Even well-preserved mammoths found in the ice didn’t freeze quickly enough for a fully intact genome to survive.

Therefore, the genetic material in cells from these mammoths is far from being complete and intact.

- You might also like: Why the passenger pigeon died out

Three degrees of impossible

So how difficult is it really to bring back a species from the great beyond using new DNA technology? According to Gilbert, there are three degrees of possibility ranging from possible to absolutely impossible.

- With a fully intact genome, you have a good chance of recreating an animal as it previously existed, at least physically. This category could include newly extinct animal species where cell samples were properly taken care of before the species disappeared, as well as tiny critters that cooled down quickly enough on their own.

- If you have fragmented genetic material, you may be able to create an animal that is very similar to the animal from which this material originates. You do this by combining the material with DNA from living relatives. This might apply to woolly mammoths found in the ice, for example.

- With no hereditary material, you have absolutely no chance of reproducing an extinct animal. This is the case with dinosaurs, for example – in other words, you’ll be hunting long and hard for Jurassic Park.

Practically speaking, only species that have recently gone extinct offer the possibility of being reintroduced.

San Diego’s Frozen Zoo is a gene bank that stores cell samples from animals in order to preserve them and perhaps reintroduce those that don’t survive. It’s a form of insurance. A similar bank for plants exists on Svalbard.

But might gene banks contribute to weakening the protection of vulnerable species? Do the banks provide an excuse to allow species to die out, because we think we can just bring them back when it suits us?

Even when the genetic material is available, not everyone agrees that we should reintroduce extinct animals – at least not with a view to giving them a role in nature. This viewpoint doesn’t aim to prevent any of the world’s most talented researchers in the field from pursuing their research.

- You might also like: The weeds the settlers spread

Just one small problem

These qualities include small ears, subcutaneous fat, blood that enabled the animals to cope with cold better and the characteristic fur. Once the gene sequences are identified, it becomes possible to breed for certain attributes.

But there’s just one major problem, which the researchers at Harvard also realize: we don’t really want the woolly mammoth to come back.

Article continues under the photograph.

“Mammoth DNA is very fragmented. The solution would be to combine this genetic material with an unfertilized egg from a female elephant,” says Professor Gilbert.

You replace parts of the elephant’s DNA in the egg with mammoth DNA, depending on the characteristics you’re looking for. The elephant is then inseminated with this modified egg.

In theory, this elephant can then produce a kind of mammoth. But actually it can’t – at least not with the technology available today.

“Mammoths and elephants are different in numerous ways. What you’d end up with is some kind of hybrid,” Gilbert says.

So you wouldn’t get a real mammoth even if the method did result in an offspring. You wouldn’t get an elephant either, at least not like the ones we’re familiar with. Perhaps you’d get some kind of hairy elephant. But it wouldn’t be a mammoth.

Since we currently can change only a few pieces of the genetic material per generation, this procedure is also very time consuming.

Why do it then?

De-extinction enthusiasts, however, talk about bringing back the mammoth in one form or another to rebalance the tundra ecosystem and for the sake of the climate.

Article continues under the picture.

Permafrost, which is continuously frozen ground, ensures that large quantities of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide remain bound up, because biological material freezes.

Supporters argue that bringing the mammoth back would have environmental benefits. The insulating snow layer covering the tundra nowadays may be contributing to melting the permafrost and perhaps increasing global warming, they say. With no large animal herds, the snowpack stays undisturbed, and the increased insulation prevents the ground from freezing as deep as before. The ground then heats up faster during the summer, releasing more greenhouse gases.

“The theory is that large herds of mammals would dig up and destroy the snow layer, so the ground would freeze more solidly. This would keep the permafrost from melting as quickly,” says Gilbert.

This is how woolly mammoth herds could help limit global warming, say de-extinction supporters.

Another argument for experimenting with this technology is that today’s elephants might become more cold resistant, allowing them to be introduced into areas where they can’t survive today and maybe increasing their chances for survival.

But that scenario is completely different from bringing back woolly mammoths. Mammoths disappeared 4500 years ago. They don’t want to come back either. At least not like they were then.

Something similar

Gilbert confirms that he doesn’t want 800 000 mammoths in Siberia.

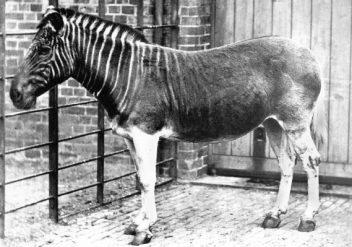

Here’s what a quagga actually looks like, from when it was in the London Zoo. But these zebra relatives are extinct now. Photo: Frederick York, Wikimedia

He has little sympathy for people with grandiose and detailed explanations as to why it’s so important to bring one or the other species back to life. He would find it more sincere if people were up front about their reasons, such as having a financial interest in the project.

“I’m much more willing to help people who are honest and say they just want something that resembles a different species,” Gilbert said.

This type of project is taking place in South Africa. There you can find zebras with stripes on the front half of their bodies and brown on their back half. They’re very similar to the quagga, a subspecies of common plains zebras that died out in 1883.

“They may look like quaggas, but they’re not,” said Gilbert.

These are common plains zebras that have been bred to increasingly resemble the quagga. But the people behind the breeding are honest in admitting they haven’t recreated the quagga. They’ve made a kind of incomplete copy.

Similar attempts have been going on for a while. The aurochs, ancestors of our own domestic cattle, existed in Europe until 1627. Habitat destruction, hunting and diseases transmitted from domestic animals were the main reasons for the disappearance of the species Bos primigenius.

The German brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck tried to breed back the aurochs in the 1920s.

“They crossed big angry, black cows and bulls, which resulted in bigger angry, black cows and bulls,” said Gilbert.

But aurochs they were not.

Is it a duck?

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck” is how the expression goes.

But actually we can’t really be sure that it is a duck.

Professor Hans Stenøien at NTNU University Museum’s Department of Natural History is fundamentally against de-extinction. He has several reasons, including the technical and methodological challenges. “There’s no guarantee that having cell cultures will be enough” for the process to work, he says.

Stenøien’s arguments are largely based on behaviour. If you use a lab to recreate an animal that has been extinct, who can teach it to behave like it needs to?

“Even if we gain control of the genetics, we can’t as easily capture the cultural aspects of animal behaviour – that is, what they normally learn from their parents,” says Stenøien.

Who’s going to teach the duck to behave like a duck? Or in this case, teach the mammoth to behave like a mammoth?

Some of the behaviour will be natural and develop on its own. But certainly not everything.

“In any case, we live in a world that will soon need to feed 10 billion people,” says Stenøien.

We might dislike – or even hate – the thought, but it may just be a brutal reality that there isn’t room on our planet for all the species any longer.

Locusts from the mountains

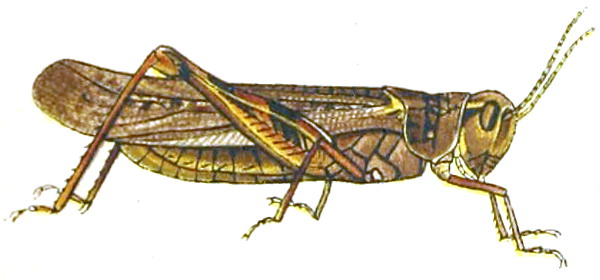

Rocky Mountain locusts would swarm down from the mountains in the western United States in the 1800s. One famous swarm sighted in 1875 covered an area over 500 000 square kilometres. That’s bigger than mainland Norway and Svalbard combined.

Melanoplus spretus. The farmers’ plague. Not nice. Nobody is arguing to bring this particular creature back from extinction.Illustration: Wikimedia, Julius Bien University of Minnesota

The locusts probably numbered several thousand billion during the years they swarmed. The species was regarded as a huge plague for the affected farmers and as one of the major obstacles to the success of westward expansion.

Melanoplus spretus is the Latin species name for these locusts. Twenty-seven years later they were extinct, perhaps because settlers had destroyed their breeding grounds.

Should we bring back this species? Can we bring back this species? Maybe.

No one anticipated the disappearance of the Rocky Mountain locusts, and that’s part of the reason so few specimens have been preserved. It may be that none are intact enough to obtain good cell samples from. At least not yet.

So far, no strong voices have argued for Melanoplus spretus’ de-extinction if that some day becomes possible.

Why not? Because people prefer to fight for sweet, beautiful and magnificent animals. Not the ones that are a nuisance to farmers.

Assuming it’s possible…

This passenger pigeon specimen is found at NTNU’s University Museum. But passenger pigeons died out more than a century ago. Photo: Per Gustav Thingstad, NTNU.

But let’s say you actually succeed. Future technology makes this possible. You bring back the passenger pigeon, which had numbered in the billions in North America but were so heavily exploited that the species went extinct in just over a century.

- You may also like: Why the passenger pigeon died out

These reintroduced passenger pigeons behave the way they’re supposed to. You breed a few thousand of them with sufficient genetic variation so they can interbreed and then you release them to…where?

Acorns were one of their main food sources. But the vast oak forests in North America are now greatly reduced, although they still exist. So you have to reproduce them too.

Whatever the end result, you’ve spent a lot of money and time to reach your goal. Is it right to spend so much money on reintroducing species that have already died out?

“This money and these resources could instead be put toward making sure that no new species go extinct,” said Professor Gilbert.

In most cases, it may be more realistic to try and take care of what we still have. This is also Professor Stenøien’s main argument.

He believes that de-extinction efforts are a wrong use of resources. “With the funds spent on reproducing extinct species, we could take care of even more endangered species that aren’t yet extinct. In my world that’s more important,” he says.