The capsule camera of the future: Images the intestines in 3D and detects disease

Norway has one of the highest prevalences of intestinal cancer in Europe, and this year sees the national screening programme being rolled out in full. But where do the capsule cameras go?

Thanks to new technology, a tiny capsule camera can examine your intestines while you get on with your work or walk your dog. Compared with the alternatives, patients experience virtually no discomfort at all.

There are many reasons to choose a capsule camera examination over traditional alternatives such as colonoscopiesExamination of the colon carried out using a flexible tube that is inserted via the rectum. and gastroscopiesExamination of the inside of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum carried out using a flexible tube which is inserted via the mouth.

However, there is just one catch: The challenges that for over 20 years have prevented this smart technology from replacing more invasive examinations have proved more difficult to overcome than many might have hoped and believed.

Here are two research pathways that will change this – and the explanation of how they are connected.

The intestines minute by minute

The capsule spends an average of 8 hours travelling through the digestive system. During its journey, it covers about the same number of metres and records more than 50,000 images.

“It goes without saying that analysing such a wealth of data is a very resource-intensive task,” says scientist Pål Anders Floor. He works at the Department of Computer Science at NTNU in Gjøvik.

Pål Anders Floor works with 3D and machine learning to enhance capsule camera technology. Photo: NTNU.

In recent years, he has been looking into the possibility of using a capsule camera to create a three-dimensional representation of the intestine.

“In combination with machine learning, a 3D reconstruction can quickly draw the specialist’s attention to possible diseases and other anomalies. As a result, no one has to sit and stare at the capsule camera’s tedious journey through the digestive tract minute by minute,” says Floor.

Imaging in fits and starts

Not only is the current method of examination time-consuming, but there is also a not-insignificant chance that disease might not be detected.

In exactly the same way as the food you eat, capsule cameras are at the mercy of the intestines as soon as you swallow them. This means that the capsule might be completely still one moment, and then suddenly shoot off the next. Unlike an endoscopeTube equipped with light and camera used to examine the inside of the body's hollow organs.which is controlled by a specialist – the capsule camera does not take time to stop and make sure it has taken good enough pictures of a polypGrowths on the mucous membranes of the intestine which are initially harmless, but which over time can develop into cancerous tumoursbefore it moves on.

“In some cases, it only manages to take a single picture of the diseased area in passing, and due to unstable light conditions, bubbles and other interfering elements, there is no guarantee that the diseased area will be clearly visible in that one picture,” says Floor.

He believes artificial intelligence and machine learning can improve the situation.

Machine learning can improve capsule cameras

The use of machine learning has led to several breakthroughs in the detection of diseases in recent years, and the gastrointestinal region is no exception in this respect. In fact, computers have already proven to be as good as or better than specialists at detecting some diseases based on capsule camera images.

Anuja Vats is researching how machine learning can improve capsule cameras’ ability to detect diseases. Photo: Mads Wang-Svendsen.

However, the computers still have certain weaknesses. For example, they are very poor at distinguishing between different diseases.

“This is partly due to a lack of data that can be used to train algorithms,” says scientist Anuja Vats.

She works at the same department as Floor and specialises in how machine learning can make capsule cameras better at detecting diseases despite the lack of data.

Training algorithms using artificial data

Machine learning requires data – large volumes of data – and since health information is subject to very strict data protection regulations, scientists cannot just pick and choose from capsule camera recordings. In addition, the recordings that are actually available usually only show one specific stage of a disease. To be absolutely sure that the algorithms actually identify these diseases, they need to be trained in the entire course of the disease.

“If large amounts of data had been readily available, it would still have required us to involve many experts for long periods to categorise them for us. We have therefore looked at the possibility of training the algorithms using artificial data,” explains Vats.

Creating artificial images of intestinal diseases

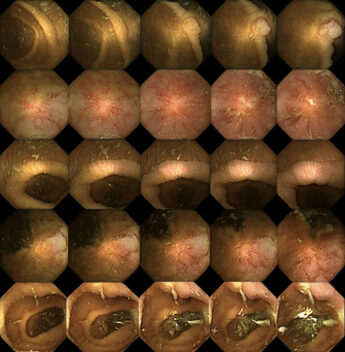

No sooner said than done! Using a so-called machine learning framework developed by scientists from the US video card manufacturer Nvidia, Vats and her colleagues have now created a series of artificial images of a selection of intestinal diseases in their various stages.

Before they could feed the capsule camera algorithms with the results, they had to make sure they were realistic enough.

Gastrointestinal specialists were shown the images, and they were largely unable to distinguish between the real images and the images developed by artificial intelligence.

“One of the major obstacles to creating a good training programme for capsule endoscopy is the lack of a good atlas with an overview of diseases in their different stages. These results make it possible to develop these kinds of atlases using artificially generated images,” explains Vats.

Complementing each other

Although their approaches are relatively different, there are strong indications that the scientific work being done by Pål Anders Floor and Anuja Vats may complement each other.

“By combining machine learning techniques that identify diseases and 3D models of the intestines, we will get a tool that not only contributes to improved and less resource-intensive capsule camera examinations, but one that can also be used in operations,” Floor explains.

He envisions several ways in which the tool can assist practising clinicians.

“By enabling surgeons to inspect the individual patients’ intestines in advance, it can be used to plan and practise prior to particularly difficult procedures. As a result, the risk of something going wrong can be reduced,” says Floor.

This may be particularly relevant in light of a new study from North Carolina State University. The study claims that not all intestines are created equal. The nature and anatomy of the digestive tract seem to vary greatly, even among healthy individuals.

Despite promising results, however, both scientists emphasise that there is still work to be done before the capsule cameras can replace other types of examinations altogether. And maybe that is not a goal in itself, either.

“The most important thing is to be able to offer a comfortable alternative to people who are reluctant to undergo more invasive intestinal examinations. Some of these examinations are associated with so much discomfort that many people simply don’t go to get examined,” says Vats.

This is capsule endoscopy:

Capsule endoscopy is an intestinal examination performed using a pill-sized camera, similar in size to a large vitamin capsule. The capsule is equipped with a battery, its own light source, and one or more cameras.

After swallowing it, the pill moves through the digestive system with the natural movements of the intestine. The video material is continuously uploaded to an external storage device carried by the patient. Subsequently, the recordings are examined by a specialist.

The pill camera was first introduced in 1999, and two years later, the examination was approved for use in the USA. Since then, there have been numerous new models and improvements to the original technology. Today, pill cameras are used worldwide, especially in examinations of the small intestine.

However, due to technical challenges, this form of intestinal examination has not become as widespread as many initially hoped.

The Research Council-funded project "Improved Pathology Detection in Wireless Capsule Endoscopy Images through Artificial Intelligence and 3D Reconstruction (CAPSULE)" aims to address this issue.

References:

Ahmad, B., Floor, P. A, Farup, I. and Hovde, Ø. (2023). 3D Reconstruction of Gastrointestinal Regions Using Single-View Methods. IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 61103-61117. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3286937

Floor, P. A., Farup, I., Pedersen, M. (2022). 3D Reconstruction of the Human Colon from Capsule Endoscope Video. CEUR Workshop Proceedings.

McKenney, E.A., Hale, A.R., Anderson, J., Larsen, R., Grant, C., Dunn, R.R. (2023). Hidden diversity: comparative functional morphology of humans and other species. PeerJ. 2023 Apr 24;11:e15148. doi: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15148

Vats, A., Pedersen, M., Mohammed, A., Hovde, Ø. (2021). Learning More for Free – A Multi Task Learning Approach for Improved Pathology Classification in Capsule Endoscopy. In: de Bruijne, M., et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2021. Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12907. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87234-2_1

Vats A, Pedersen M, Mohammed A, Hovde Ø. (2023). Evaluating Clinical Diversity and Plausibility of Synthetic Capsule Endoscopic Images. Sci Rep. 10857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36883-x