The museum treasures that never see the light of day

Some of the greatest natural treasures at NTNU University Museum are never put on display. Many of these objects were collected on famous expeditions or obtained in other ways. One such treasure is Charles Darwin’s coralline algae.

One problem with writing about NTNU University Museum in Trondheim is that it is a never-ending story. You constantly come across new and exciting things that beg to be shared. But perhaps it is not so strange after all – the people working at the museum have plenty of amazing stories to tell.

“At first glance, it’s just detritus,” said senior engineer Tommy Prestø, holding out a box.

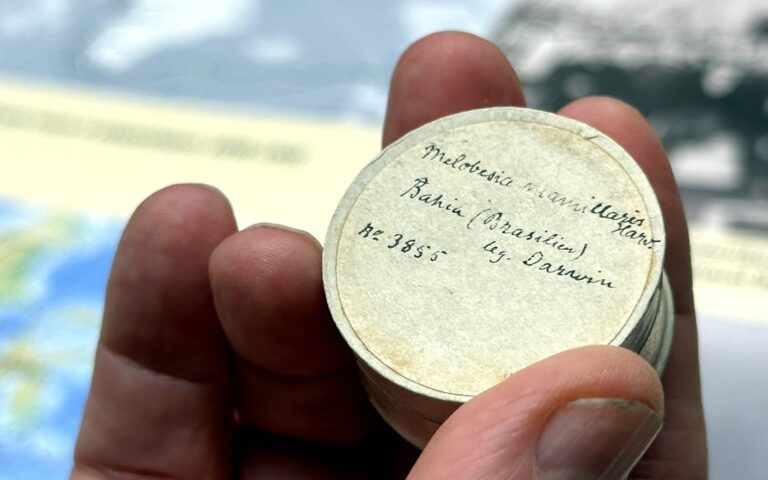

And he has a point. In the box from the storage room lie a few fragments of coralline algae, and if you didn’t know better, you might feel quite underwhelmed. But if you take a closer look, you will notice the name on the box – one that makes even the most seasoned biologists weak at the knees – ‘Darwin’.

But the lid reveals that the debris is in fact a calcareous alga collected by none other than Charles Darwin himself. Photo: Nina Tveter, NTNU

This specimen was collected by Charles Darwin during the expedition with HMS Beagle in the 1830s. It was sent to the renowned algae expert Mikael Heggelund Foslie many, many years ago, and the museum in Trondheim has two of these boxes in its collection. More about that later.

NTNU University Museum has many artefacts that are never exhibited. However, even though months or even years may pass between each time the museum offers a tour of its storage rooms, it is possible to join a tour if you are in Trondheim, of course. Just keep an eye out on the museum’s website if you happen to be in the city.

Expert collection in the ‘brewery cellar’

Among the experts who can show you the hidden treasures are Prestø and Kristine Bakke Westergaard from the botany department, and Torkild Bakken and Karstein Hårsaker from the zoology department.

Prestø and senior engineer Hårsaker are standing at the bottom of some dimly lit stone steps down into the so-called ‘brewery cellar’. Despite all sorts of plans and half-hearted promises of new facilities, much of the museum’s animal collection is still stored behind these old walls.

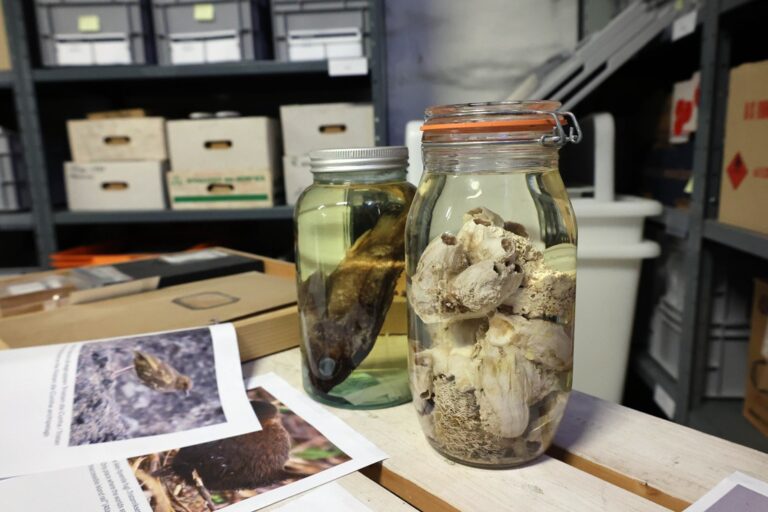

Hårsaker shows us some objects from the volcanic archipelago Tristan da Cunha, located far out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

“It is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world,” said Hårsaker.

Remote places can be an eldorado for biologists because there is a good chance of finding species that do not exist anywhere else. In 1937, a Norwegian research expedition travelled to the islands, sponsored by Norway’s Freia chocolate factory, among others.

“The inhabitants of Tristan da Cunha were said to have unusually fine teeth,” explained Hårsaker.

So Freia and the Norwegian Dental Association were among those who thought it would be a good idea to contribute to science. They sent along a dentist to extract some teeth that they could then examine. However, marine biologist Erling Sivertsen was the only employee from the museum in Trondheim who took part.

“That is why we mostly have specimens from the sea,” explained Hårsaker, pointing to a colossal barnacle and a fish called a Cape redfish (Sebastes capensis).

A colossal barnacle and a fish called the Grey Triggerfish (*Sebastes capensis*), collected from Tristan da Cunha in 1937. Photo: Nina Tveter, NTNU

In total, the researchers collected thousands of specimens, including 97 animal species and 150 plant species that were completely new to science. The flightless Inaccessible Island rail and a species once thought extinct but happily very much alive – the Tristan thrush – were among them.

The study of the population’s teeth was used by professionals and politicians when planning Norwegian health policy after World War II. Talk about getting a lot out of one expedition!

Almost 1.7 million stories in the storage rooms

How about a royal python? These days, it’s rare for live animals to be collected. Many of these have been here for a long time. Photo: Nina Tveter, NTNU

The museum has almost 1.7 million natural specimens in its storage rooms, each with its own unique story to tell. In other words, the public exhibitions showcase only a fraction of what they have.

A few flights of stairs up from the ‘brewery cellar’ are some more modern storage rooms where the museum stores its botanical specimens.

The specimens were often collected on expeditions that seem arduous and intriguing even by today’s standards. Museum experts still go on expeditions, although they now usually call it ‘fieldwork’ instead.

Admittedly, many of the trips these days are not to the other side of the world; and often they are just around the corner – mostly because it is difficult to get funding. It is really quite strange – it seems we can afford everything nowadays, except mapping the natural environment to find out what we had, what we have, and what we stand to lose if we are not careful.

Associate Professor Kristine Bakke Westergaard is one of the people who still gets to travel to exotic places.

- You might also like: Hundreds of thousands of dead in the basement

Solving mysteries

Bakke Westergaard is a botanist. She often works in Arctic regions and studies invasive species that spread to places they really should not. That’s a story for another time, but you can get a taste of what to expect in this article. So, what exactly is her connection with the collections?

Kristine Bakke Westergaard is a full-fledged nerd and the curator of the vascular plant collection at the museum. She’s also the kind of person who travels to exotic places to learn just a little bit more. Photo: Nina Tveter, NTNU

Well, first of all, she is the curator of the vascular plant collection. She has also studied nunataks in Greenland. These are mountain peaks that protrude above the glaciers and have never been glaciated. Nunataks and other ice-free areas may have served as refuges for some plant species during the last Ice Age.

“One of these plants is the northern single-spike sedge,” said Bakke Westergaard.

The plant is almost exclusively found in far eastern Russia, in North America and in Greenland.

But northern single-spike sedge is also found in three locations in Nordland County,” added Bakke Westergaard, clearly someone who enjoys a mystery.

Why is this plant only found in far-flung places, and then in a few isolated spots here in Norway, but nowhere else in Europe? Did the plant survive here because it found sanctuary on a nunatak?

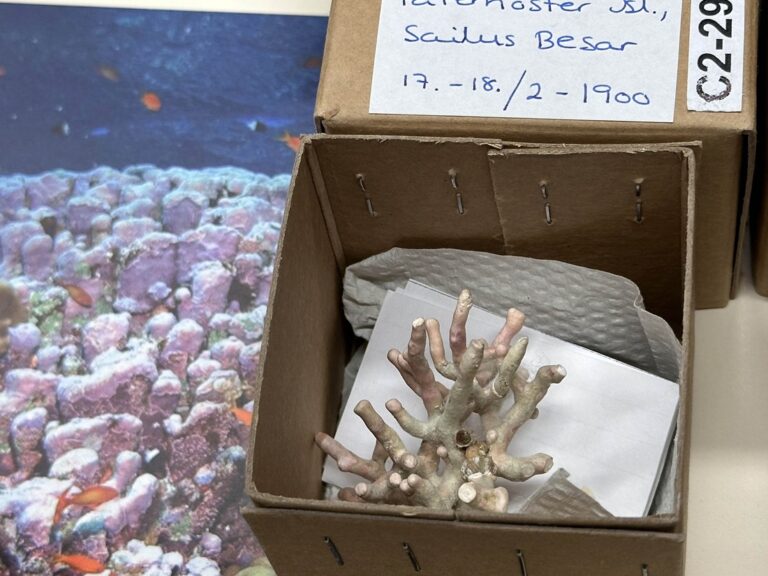

A calcareous alga is, after all, far more beautiful than most of the animals preserved in alcohol. Photo: Nina Tveter, NTNU

Figured it out

In this kind of work, she and others can learn from plants that were collected long ago and later ended up here in the storage rooms.

Flora was collected in Greenland by people like Professor Olav Gjærevoll and the renowned naval officer Jens Arnold Diderich Jensen. Their work shows that plants such as alpine fescue, purple saxifrage, roseroot, grayleaf willow and our mystery plant northern single-spike sedge existed on Greenland’s nunataks in recent times.

Discussions about why this plant existed in Norway went on for almost 150 years before Bakke Westergaard found the answer after 15 years of genetic research and fieldwork in three U.S. states, Greenland and Nordland County.

“The answer is yes.” And she was thrilled when she figured it out.

She believes the plant survived the Ice Age in ice-free areas of Norway, and you can read more about it here (in Norwegian).

(But remember, these are true nerds – so some people are still debating the matter.)

Foslie and 38 expeditions

But back to those fragments from Darwin and how they ended up here at the museum.

Mikael Heggelund Foslie was born in 1855 and worked as a telegraph operator in Lofoten, but his great interest was natural history. He was incredibly lucky, and so was science: Anna Jensen, a driven woman from Drammen, moved to Northern Norway to work as a governess. The two quickly hit it off and got married, and Anna spurred Mikael into action.

“She was a great inspiration,” said Prestø.

Anna Jensen persuaded Foslie to follow his dream and focus on biology – and thank goodness for that.

Foslie went on to become an outstanding botanist and one of the world’s leading experts on coralline algae. Experts sent him specimens from far and wide, asking if he could analyze them.

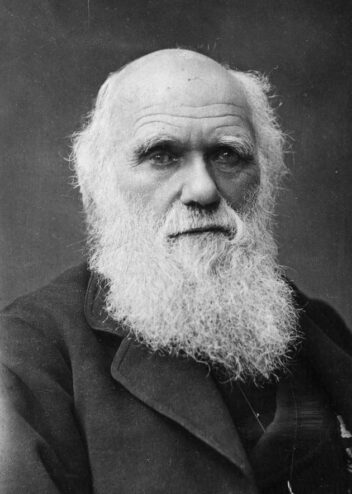

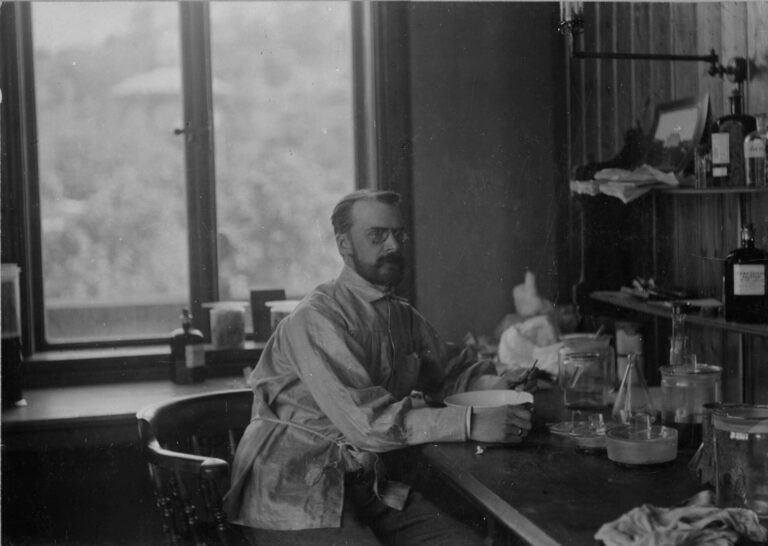

The botanist Mikael Heggelund Foslie was an expert on calcareous algae. Photo: NTNU University Library

“We have found specimens from 38 different expeditions,” said Prestø.

Eventually, both Foslie and the material ended up in Trondheim, where he worked until his death in 1909.

Among these 38 expeditions was the famous Fram II expedition, led by the renowned polar explorer Otto Sverdrup. Some of the material from this expedition can also be found here in the museum’s storage rooms.

But the most famous of all are the tiny fragments from Darwin’s expedition with HMS Beagle.

- You might also like: A tiny arctic shrub reveals secrets of plant growth on Svalbard

Darwin’s fragments

Almost all the specimens Darwin collected are in the United Kingdom, but, as mentioned, two small boxes are kept here in Trondheim.

These tiny fragments are reproductive parts taken from a coralline alga, which Foslie was an expert on. He needed these reproductive parts to identify the species, and so they were sent to him from England. A letter at the Gunnerus Library confirms that this is how it happened.

“The specimen was collected in Bahia in Brazil in 1832,” Prestø said.

After a detour via England, it has now become a tiny but striking part of NTNU University Museum’s collections.