Researchers want to find out why quick clay is so unstable

Quick clay collapse can be both dangerous and costly. New research will help us understand more about why the clay is so unstable. And maybe what we can do about it.

In brief

Quick clay is actually an old seabed. The clay thus formed under water, but came to the surface when the landscape rose after the last ice age.

However, this clay was not so dangerous at first, because it was full of salt from the sea. Only when the salt in the clay was washed out of fresh water from rain and groundwater did it turn into quick clay.

But what exactly makes quick clay so unstable?

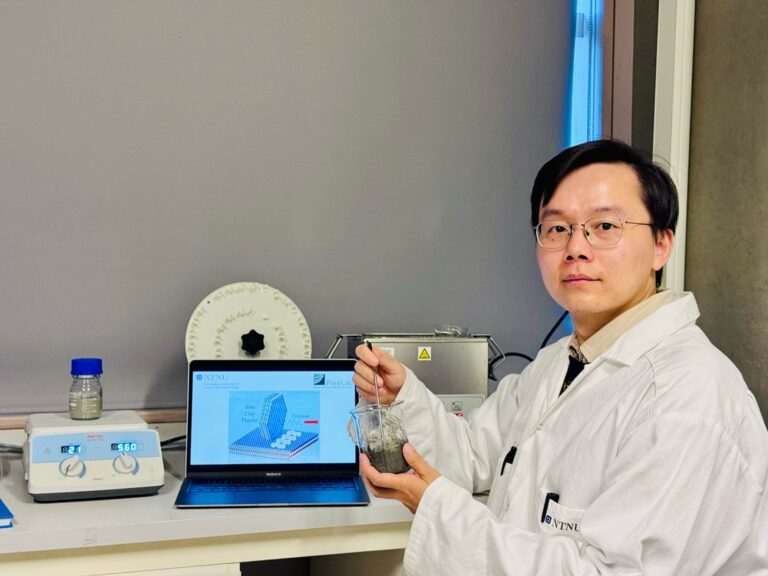

“We have made very detailed and careful simulations of the friction between clay particles,” says researcher and doctor Ge Li at PoreLab and the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Production at NTNU.

A new article from Ge Li and Professor Astrid Silvia de Wijn from the same institutions deals with what happens at the nano level when the clay becomes weaker because fresh water replaces salt water.

Important for many to know more about quick clay

This work is particularly important for us in Norway. In this country, a large number of people live on quick clay, many of these in Eastern Norway and in Trøndelag. But there are also significant amounts of quick clay in Sweden, Finland, Canada, Russia and Alaska, and the research is therefore important for many more people.

“We see that the ions in the salt water settle on the surface in certain places and make it more difficult for the clay particles to slide against each other. In other words, the ions make the surface uneven and stand in the way of slippage,” says Ge Li.

Ions are electrically charged atoms or molecules. In this case, the ions from the salt help to keep the clay stable.

Dramatic consequences

Building on quick clay can have dramatic consequences. In 2020, a mudslide in Gjerdrum took 31 housing units with it. Ten people died in the landslide, while ten others were injured. Around 1000 people had to evacuate their homes.

A quick clay avalanche in Levanger in August this year took parts of the E6 and the Nordland Line with it. One person died. Several months later, both the road and the train line are still closed. This has cost society several million every day.

Will find a more gentle alternative

Stabilising quick clay is both expensive and can have significant consequences for the environment.

“When we stabilise quick clay today, we mix and inject lime and cement. But we don’t really know how it works. The production of lime and cement also emits a lot of CO₂, which is not good for the environment,” says Ge Li.

You might think that it was possible to inject the quick clay with salt instead. In the laboratory, it may look like this, but in practice this will not work.

“However, our hope is that by better understanding how the salt works, it will be easier to find better and more environmentally friendly ways to stabilize quick clay,” says Ge L.

The work is part of a large interdisciplinary project called Sustainable Stable Ground funded by the Research Council of Norway. This includes people from civil and environmental engineering, the Department of Structural Engineering, Chemistry, Physics and the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI).

Reference:

Ge Li, Astrid S. de Wijn, Molecular dynamics simulations of nanoscale friction on illite clay: Effects of solvent salt ions and electric double layer, Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Volume 703, Part 1, 2026, 139107, ISSN 0021-9797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2025.139107