When a baby’s small movements have big consequences

A breakthrough method from the 1990s is now being transformed into an AI-powered tool to help doctors diagnose cerebral palsy.

Imagine you’re a parent with a newborn who might be at risk for cerebral palsy. Maybe your baby was born too early. Maybe there were problems with the birth: an infection or trauma that interrupted the blood flow to the baby’s brain.

You’d often have to wait for a definite diagnosis – perhaps until your child turns two. That’s a long time for a parent to wonder – and even more critically, it prevents caregivers from offering help at a time when a baby’s brain can best respond to treatment.

So, when Lars Adde, a physiotherapist working at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at St Olavs Hospital, first heard about an Austrian doctor’s breakthrough approach to early diagnosis of cerebral palsy in the late 1990s, he was all in.

In the early 2000s, he and several colleagues from his department decided to bring the technique, called the General Movement Assessment, to Trondheim.

To the trained eye, these movements are noticeably different in a baby that will later develop clear signs of cerebral palsy.

“We trained in the General Movement Assessment technique, and we did a lot of studies implementing this tool in the clinical follow-up program here at the hospital from 2002 to 2019,” he said on the latest episode of 63 Degrees North, NTNU’s English language podcast.

- You might also like: Babies are born to learn – and they learn by moving

How it works

The General Movement Assessment technique, despite its clunky name, relies on a surprisingly simple idea: an infant lying on its back will spontaneously move its arms and legs in a seemingly random way. Doctors use the word fidgety to describe the movements.

“It’s like small dancing movements in the whole body. And it’s like the infant is orchestrating the world while waving its arms and legs,” Adde said in the podcast.

But to the trained eye, these movements are noticeably different in a baby that will later develop clear signs of cerebral palsy – the movements are stiffer and cramped.

“You have spontaneous movements, but the quality of them is very different. This is what we call the lack of these fidgety movements. The fidgety movements that are variable are not there. And this is a sign that gives this child a higher risk,” Adde explained.

- You might also like: Ultrasound can prevent brain damage in sick newborns and premature babies

A valid approach – but not widely adopted

Adde and his colleagues embraced the technique and worked together as a team to evaluate videos of infants from the NICU who might be at risk.

The sustainability of really having these general movement assessment teams in hospitals, all the places they are needed, it’s not possible in practice.

But when they were talking to colleagues outside of Norway, they realized that the General Movement Assessment wasn’t as widely adopted as you might think. They were initially surprised because the technique promises early diagnosis of cerebral palsy in infants long before the standard approach would give a definitive diagnosis.

But both time and money could prove a significant barrier.

“You need a lot of training. It’s quite expensive to take these courses and to take this education, you also have to practice all the time to observe videos. So the sustainability of really having these general movement assessment teams in hospitals, all the places they are needed, it’s not possible in practice,” he said.

- You might also like: Saving lives in Sierra Leone – one C-section at a time

Videos from across the globe – and computers that look for patterns

That got Adde to thinking: videos could be assessed with the help of a computer. Would that expand the ability of NICU doctors to use this early assessment technique to identify infants most at risk?

To test this idea, Adde and his colleagues needed a collection of videos of infants from across the globe to establish what was normal and what would be an indicator for cerebral palsy. So that’s what they did.

“We set up multi-site center studies, clinical studies. We cooperated with four hospitals in Norway. We cooperated with two big hospitals in Chicago, in the United States, and with a big hospital in the southern parts of India and also in Belgium, Denmark, Turkey,” he said.

Eventually, he and his collaborators collected videos of about 600 infants and followed the infants all the way until they were between three and five years old. That way they knew without a doubt which infants would eventually develop cerebral palsy.

- You might also like: The smallest premature babies are less physically active as adults

Home videos and 19 data points

Along the way, the researchers realized that they could probably let parents take videos of their infants themselves, and they set up a study to make sure the videos were equally useful as videos made in the hospital. The study clearly showed the home videos worked well.

Now any family that is being followed up after a stay at the NICU at St Olavs is asked to do a video recording of their infant at home before they come in for their three-month checkup.

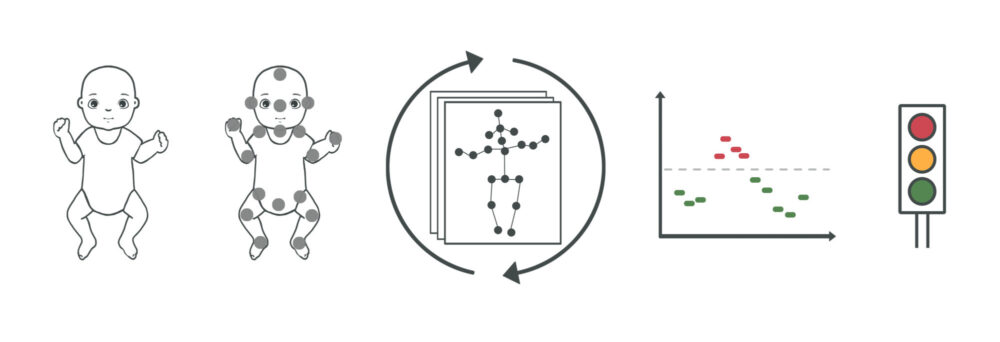

The researchers also developed a computer motion tracker that made it possible to track 19 body points from the digital video images.

“We trained an AI algorithm to do motion capture from 19 different body points. We were sitting with 20,000 frames from different videos, and we were annotating: where is the nose? Where is the right and left wrist? Where is the right and left ankle? So we clicked in these positions manually in 20,000 frames. And then we used this data to train an AI model to automatically track these positions from videos,” Adde said on the podcast.

A clinical study using the AI algorithm found a correlation between the movement data from the 19 positions and the cerebral palsy or no cerebral palsy diagnosis. It was one of the first such studies internationally to make this connection, Adde said.

The Norwegian Open AI team that worked on the AI algorithm. Back row from left: Felix Temple, Kimji Pellano, Inga Strümke, Heri Ramampiaro. Front row from left: Espen Ihlen, Lars Adde, Daniel Groos. Photo: NTNU

The next steps

As the utility of the AI motion tracker as a diagnostic tool became clear, Adde reached out to NTNU’s Technology Transfer Office, the TTO. As a university employee, you’re required to do this if you have something you think could be commercialized.

The TTO thought his idea was good. At first they thought they could find an industrial partner to license the solution from the university.

But after a couple of years of unsuccessful efforts, they elected to pursue a different approach.

“What we realized is that it was not straightforward to get an industrial partner on board We then got the idea, let’s try another way,” Adde said. “It’s a hard way, it’s a difficult way, it’s a probably a long way. And that was to establish a startup company ourself.”

This illustration shows how the entire In-Motion Technologies AI tool works. From left: an infant lies on its back and is filmed by its parents. The video is processed by computer which identifies the 19 important body parts in the video. The In-Motion Technologies AI tool assesses the infant’s movements and assigns a risk of cerebral palsy for every five seconds of video, which a doctor can review simultaneously while viewing the video. Illustration: The NTNU In-Motion Project

New company, and regulatory hurdles

This new company is called In-Motion Technologies and has just two employees, including Adde.

The company has a mock-up of how their AI tool could be used by doctors as an aid in diagnosis and is trying to find investors.

And because software of this type is regulated as a medical device, it has to be approved by regulators. That in itself can be a long and challenging process.

Another challenge relates to the fact that AI is involved, which is also regulated. Part of the regulatory process involves being able to understand and explain how the AI makes its decisions from the information it has been given.

That’s not easy either. The way that AI makes judgements is kind of opaque. Computer scientists refer to the AI’s internal assessment processes as a black box. Adde and his colleagues have finally begun to crack open that black box to understand how AI makes its predictions so they can get the software approved.

It’s been quite a journey for someone who began his career as a young physiotherapist, hoping to make the lives of at-risk infants better.

“I have been in the clinical field, I’ve been researcher for many years, and now I’m also an entrepreneur. So I had three hats, so lots of hats. It’s a little bit challenging, but it’s very fun. From the beginning, my motivation was to find new tools to give better help to small infants,” Adde said.

You can hear more about his transformation from NICU physiotherapist to medical researcher and now entrepreneur in the second half of the latest episode of 63 Degrees North:

References:

Prechtl, Heinz FR et al.An early marker for neurological deficits after perinatal brain lesions The Lancet, Volume 349, Issue 9062, 1361 – 1363

Lynn Boswell, Lars Adde, Toril Fjørtoft, Aurelie Pascal, Annemarie Russow, Ragnhild Støen, Niranjan Thomas, Christine Van den Broeck, Raye-Ann de Regnier, Development of Movement and Postural Patterns in Full-Term Infants Who Are at Low Risk in Belgium, India, Norway, and the United States, Physical Therapy, Volume 104, Issue 10, October 2024, pzae081, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzae081

, et al. In-Motion-App for remote General Movement Assessment: a multi-site observational study.

Groos DAdde LAubert S, et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning Method to Predict Cerebral Palsy From Spontaneous Movements in Infants at High Risk. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2221325. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.21325

K. N. Pellano, I. Strümke, D. Groos, L. Adde and E. F. Alexander Ihlen, “Evaluating Explainable AI Methods in Deep Learning Models for Early Detection of Cerebral Palsy,” in IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 10126-10138, 2025, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3525571