The Norwegian who built the world’s roads

The Flåm Line railway, the Trans-Iranian railroad, Ethiopian roads and many Norwegian airports. A little known professor and engineer at the Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) helped to build them all.

The novel “The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared” by Jonas Jonasson tells the fantastic story of a practical country boy from Sweden who, through luck and skill in his profession, travelled the world and worked in the backdrop of history’s great events over the last hundred years. It’s a bit like the blockbuster American movie “Forrest Gump.”

Norway has a similar story, albeit an absolutely true one, about engineer Ole Didrik Lærum. His nephew of the same name has described Lærum’s life in his book, Ingeniøren og eventryret (The Engineer and the Adventure), released in Norwegian on March 16, 2015.

Lærum was born in Voss, Norway in 1901. He was the eldest son of a doctor, and a good pupil who graduated secondary school at age 16 with top grades. In 1919, he was admitted to the Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) as a civil engineering student. In 1996, NTH became a part of the newly created Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

In Trondheim he met Sigrid Tessem, whom he later married. Lærum graduated from NTH as the country’s youngest engineer at age 21, and that was when the adventure started.

Complicated construction in mountain and fjord country

Lærum’s first engineering job was as a temporary assistant engineer for the Norwegian State Railways (NSB), where he played a part in the construction of the Flåm Line, a branch of the Bergen Line railway. The Flåm Line created a rail connection between Sogn og Fjordane county and the rest of the country for transporting goods, especially for agricultural products from the fertile county.

The Flåm Line railway is 20 km long and has an elevation difference of nearly 900 meters. Today it is a major tourist attraction, running from Myrdal station on the Bergen Line through the narrow and steep Flåmsdalen valley to the village of Flåm. Work was challenging, with constant rock fall and avalanches in the area.

Lærum learned a lot from this work, especially in the construction of eight tunnels. In 1928, he was assigned to work on the Hardanger Line from Voss to the end of Granvin fjord in Hordaland county, south of Bergen, but he did not find this work as exciting.

After seven years at NSB, no more work was to be had there. Lærum moved back to Trondheim with his wife and children, and was hired as an assistant in the Department of road and railway construction at NTH. The salary was poor, but it was the Great Depression and difficult to find work. Many of Lærum’s classmates got jobs abroad where technological developments had advanced further, and eventually Lærum also found work far beyond Norway’s borders.

A railroad through the length of Iran

Lærum joined the Danish engineering firm Consortium Kampsax. The firm built railways in Denmark and Turkey, and eventually also received an offer to build the Trans-Iranian railway. The Iranian king Reza Shah Pahlavi (Kahn) wanted to build a railway from the Caspian Sea in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south- and he wanted the construction to be completed within six years.

The firm started with over a hundred engineers, but they needed more and advertised all over Scandinavia. Lærum applied and was immediately hired. And so Lærum family life was disrupted again, and this time their journey took them to the Middle East.

Lærum came to Iran’s capital Tehran in June 1933. Kampsax had established their Iranian division in the residence of a former prime minister, and now 150 engineers from Scandinavia, Switzerland, Armenia and Iran were working there. Lærum quickly rose through the ranks and was assigned many responsibilities and important managerial tasks.

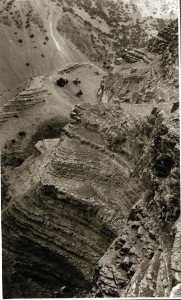

In 1935 he assumed one of Kampsax’s leading technical positions, and in 1937 he became head of the company’s laboratory. He was also deputy commander for the north line of the Trans-Iranian railway, which was a challenging landscape. The route went through hilly terrain with high, steep mountains and deep gorges and valleys. The soil conditions were difficult, and they had to build many tunnels and bridges along the way. Lærum was able to make good use of his Flåm Line construction experience.

Over sticks and stones in the Middle East

The engineers and workers who built the north line had to travel through the countryside by foot when they were planning the route. The danger of landslides was omnipresent, along with raging rivers that they had to cross in simple canoes and wild animals they couldn’t name. Lærum’s nephew describes this strenuous work in his recently published book:

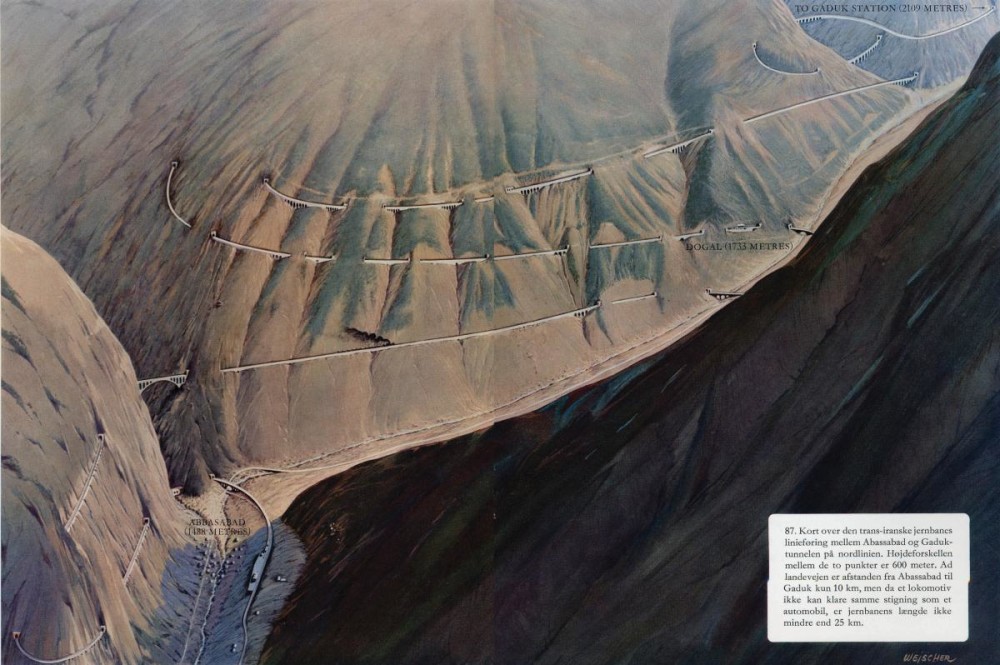

In its time, the northern part of the Trans-Iranian railroad was considered one of the technically most interesting railway lines in the world and also one of the most picturesque. The line made an uninterrupted ascent through a massive mountain range from the Caspian Sea up to 2100 meters above sea level. Since trains require a much gentler grade than cars, the route climbed in a figure eight form, with up to three levels lying one above the other. Countless tunnels and bridges, sometimes requiring daring construction, were built to accomplish this feat. The line often had to curve around inside a tunnel and come out at a higher level, crossing its own path with a viaduct.

(Article continues below)

Along the way numerous technical problems came up that had to be solved on the spot, and engineers constantly had intense discussions over maps and drawings in camp. Separate survey brigades scouted the terrain before routes were determined, and this work was especially dangerous in some areas. The route crossed rivers and flooded areas, ravines and valleys, which led to the construction of many monumental arched bridges and viaducts in artificial or natural stone.

Building tunnels made great demands on the entrepreneurs. Hidden dangers lurked daily, in the form of landslides, crashing boulders, underground water veins that suddenly broke through, and escaping toxic and occasionally explosive gases. Workers had to construct 250 tunnels over a distance of more than 80 kilometres in this region. With the existing technology of the day and difficult and loose rock types, this was quite the enterprise.

The whole operation took 55,000 men, 600 million work hours, and a half-million tons of cement. Workers built 250 tunnels, nearly 3,500 bridges, and moved 21 million cubic metres of earth. And they finished the railroad 9 months before the six-year deadline.

A luxurious life in the Shah’s palace

After the work was finished, Lærum and several others in the firm’s leadership chose to remain in Iran to continue construction work for Kampsax. Several of them were honoured with the Peafowl Order, Iran’s highest order.

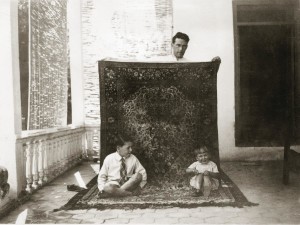

The Lærum family lived in luxury in the Iranian capital, and developed a penchant for hand-knotted Persian rugs. (Photo: Private).

When they moved to Iran, Lærum bought a house for the family in Tehran’s city centre that had belonged to a prince of a former dynasty. The family maintained a staff of up to 12 employees. Tehran was three times as large as Oslo at the time, but lacked a municipal water infrastructure and sewage system, and conditions were primitive.

The Iranian Shah was involved in the railway efforts, and Lærum often met him through his job. They eventually made personal contact, and the family was invited home to the Shah’s palace. Lærum and his wife were guests when the Crown Prince married an Egyptian princess.

In the course of his years abroad, Lærum went from being a somewhat shy and disillusioned engineer to a well-spoken man of the world who was accustomed to associating with the upper echelons of society. In many ways, the family lived a life of luxury, yet it was also a challenging time of political unrest in Tehran.

Lærum and his wife Sigrid each slept with a pistol under their pillow, and they struggled with illnesses that are typical of tropical regions with varying hygienic conditions. Lærum travelled frequently and contracted tropical diseases like amoebic dysentery and malaria, which would affect him the rest of his life.

Appointed Norwegian Consul General

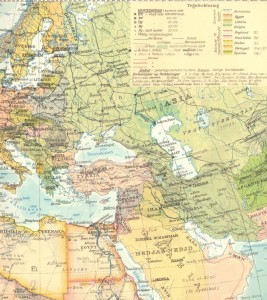

From Norway via Denmark to Iran and Ethiopia, Lærum built his way through three continents. (Photo: Private).

In 1941, Iran was invaded by the Soviet Union and Great Britain, and Kampsax’s new employer suddenly became the British government. Kampsax was contracted to transport several million tons of supplies from the Persian Gulf, through the Iranian mountains and highlands, to the Soviet front lines in the north. In addition to using the railway, the road system had to be expanded and improved.

Lærum was second-in-command to the director of Kampsax for this effort, and he had 90,000 men under him in a military role at the height of the project. Eventually, he received several more military assignments, many of them secret, and he served as a travelling consultant for the British in Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and southern USSR. While with Kampsax, he built 19 airports, which served as bases for war operations throughout the Middle East.

Lærum was appointed Norwegian Consul General in 1941, and had to attend gatherings of diplomats as a representative of Norway (i.e. the London-based Norwegian government in exile). He became good friends with the British ambassador to Iran, Sir Reader Bullard, and often travelled to the Norwegian ambassador in Moscow, who was his immediate supervisor as consul general. And so he also participated in the social life in the Russian capital.

Adviser and postman for Emperor Haile Selassie and King Haakon VII

After a period of unrest in Iran and internal strife in Kampsax’s Tehran division, Lærum decided to look for new work in the autumn of 1943. During the fall, he went on several missions abroad for the British government, and started his own consultancy and engineering company, called Nortrak. He took on some contract work in Ethiopia where his friend Bullard then lived.

Lærum wound up being engaged as Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie’s personal adviser on transportation issues. With this appointment, the Lærum family decided to move from Tehran for good and settle in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia toward the end of 1944. Lærum received contracts with both the Ethiopian government and the British Delegation to develop the primitive road system and construct airports.

(Article continues below)

After only a year, it was time for the family to move again, this time home to Norway. Lærum carried a package for King Haakon VII of Norway from Emperor Selassie with him on the journey. The two heads of state had in fact met when they were both in exile in London during the war years. Lærum’s first event, upon finally having Norwegian soil underfoot after many years abroad, was an audience with the King.

Then it was off to Trondheim again. On the basis of his long practice as an engineer at a high level, Lærum began a professorship at NTH on January 1, 1946. He worked on road and railway construction, and developed a new field of study in airport construction. He immediately became popular among students with his exciting stories from his travels abroad. More the practical engineer than a scientist, he brought a wealth of experience from his time as laboratory manager and from testing materials for Kampsax in Iran.

Norway’s foremost expert on transportation

NATO was created in 1949, and with the start of the Cold War, the arms build-up began. Norway also began to build up its armed forces and develop airfields. Military facilities needed upgrading and infrastructure. In 1952 the temporary, independent Defence Installations Directorate (FAD) was created, and Lærum became its installation manager. NATO in Paris had to approve all projects before they could be started, and FAD reported regularly to the Ministry of Defence about their businesses.

FAD was given responsibility to develop airports such as Lista, Torp, Rygge, Gardermoen, Ørlandet, Bodø and Bardufoss. Lærum was also engaged as a consultant for the Aviation Directorate and was responsible for the expansion of Sola Airport in Stavanger. Since he was a worldly and articulate expert with clear political opinions, he also served as an adviser to NATO in Paris and the Norwegian Air Lines (DNL).

In 1960, FAD closed down and the staff transferred to the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB). Lærum went back to work at NTH in Trondheim, where he concentrated on what he knew best: railway construction, airport construction and road building. He was regarded as one of the nation’s foremost experts in the field, and still had a number of external contracts in addition to his NTH position. Among other things, he assisted on the Public Roads Committee, which the Gerhardsen government created in 1964.

Lærum’s wife Sigrid died in 1963, and in 1965 he resigned from his position at NTH and moved to Bergen. There he established a branch of a consulting firm headquartered in Oslo, but he returned to Trondheim after two-and-a-half years. Eventually his health worsened and he died in 1972.

And thus ended the story of Ole Didrik Lærum, the real “hundred year-old who climbed out the window and disappeared.” He was Norway’s youngest civil engineer, who built the country’s most popular rail line, carried out breakneck ventures in Iran’s wild mountain landscapes, and frequented the Shah’s palace and Moscow’s social life. He was a consultant, an ambassador and an adviser to national leaders on three continents, and he also built the infrastructure that ensured Norway’s regional survival.