Icelandic drinking horn changes our understanding of St. Olav

After the Reformation, Norway’s Olav Haraldsson was no longer supposed to be worshipped as a saint. An Icelandic drinking horn offers some clues on how the saint’s status changed.

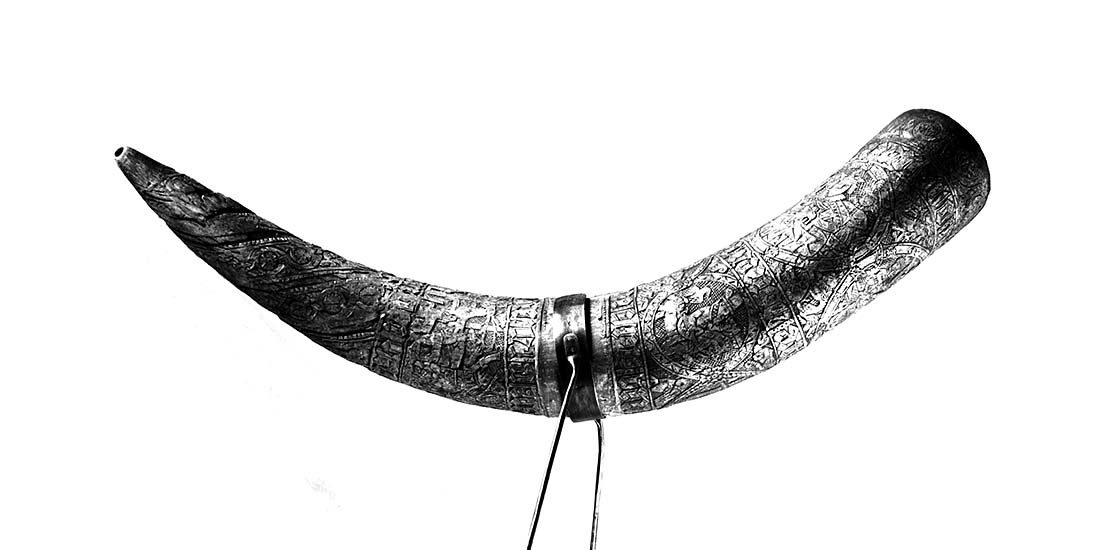

Detail from the Three Kings horn: King Olav was depicted very similarly to the way he was shown in Catholic times as a saint-king, throned and wearing a cassock and cape that were in vogue in the 1200s. He was portrayed this way – on sculptures of saints in churches and on pilgrim badges that were worn on clothing – throughout most of the Middle Ages. In the 1600s, these garments were considered old-fashioned, which indicates that this horn placed Olav in an historical context. Photo: National Museum of Iceland

Drinking horns were considered valuable objects, and they were imbued with great symbolic value in the Middle Ages. Among other things, it was said that these kinds of horns came from the foot or claw of the fabled griffin. Drinking horns often had names, and they were status symbols and collector’s items. Some were stolen and many ended up in princely cabinets.

“Mediaeval drinking horns are scattered in collections throughout northern Europe. They were coveted collectibles. Mediaeval art often remained in churches until it went out of fashion or was removed due to errors in iconography, whereas drinking horns ended up in princely collections and cabinets and have kept their status to the present day,” says Associate Professor Margrethe Stang in NTNU’s Department of Art and Media Studies.

Stang is an art historian and has recently begun studying how St. Olav has been depicted on Icelandic drinking horns. She wrote her thesis on sculptures of St. Olav, and has been interested in the saint-king ever since.

- You might also like: Iron-age Norwegians liked their bling

Queens with drinking horns

She recently shared her knowledge of saints and pilgrims on the Norwegian Public Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) TV series Anno, which gave viewers a glimpse into what life was like around the time of the Reformation in the 1500s.

“Saints and the cult of saints were an important part of life and an integral part of the culture. It wasn’t just about something that happened Sunday morning for people; it concerned their whole lives. People then were as familiar with the saints as people today are with which are the best football teams,” says Stang.

It was while working on an article about the chess pieces from the Isle of Lewis that Stang took a closer look at the queen figures on the chessboard.

Some queen figurines from among the ancient Lewis chessmen hold drinking horns. This discovery was the start of Stang’s interest in drinking horns.

“A few of them each hold their own drinking horn. It made me curious about the significance of drinking horns in the Middle Ages, so I started to dig into it and found a small group of drinking horns, particularly Icelandic ones, that depict St. Olav,” she says.

The Reformation brought an end to the worship of Catholic saints, and St. Olav was no longer to be considered a saint. The motifs on the Icelandic drinking horns show that the saint-king acquired a new role.

St. Olav is portrayed on the drinking horns “alongside biblical ideal kings like King Solomon and King David and historical figures like Charlemagne and Constantine, the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire. It’s clear that the old Catholic saint is being depicted in a new context, as an historical king and not a saint-king. He was given a new role. The horns show a shift in the perception of Olav,” Stang says.

- You might also like: The toy boat that sailed the seas of time

Kings of the time

Stang suspects that Olav was regarded as a saint, even after the Reformation.

Margrethe Stang was recently on the NRK TV series Anno, where she shared her knowledge of saints and pilgrims and gave viewers a glimpse into what life was like in Norway around the time of the Reformation in the 1500s. Photo: NRK

“When Christian IV travelled to Norway in 1599, we know that a toast to St. Olav was raised during a peasant wedding. The fact that a culture existed to toast the saints gives great context for the drinking horns. The horn motifs reflect their use and show the close relationship between them,” she says.

Depicting saints on drinking horns was common even before the Reformation, according to Stang, but it seems that the Olav motif was particularly popular in the decades around 1600.

“There was an interest in contemporary historical figures during the Renaissance. Kings were current figures, and the king was also the head of the Church,” says Stang.

- You might also like: Viking raids protected precious artefacts

Local saint variations

Norwegian drinking horns are smooth and have inscribed metal mountings, while Icelandic ones consist only of the horn. However, they are richly decorated with reliefs carved into the horn itself.

Why St. Olav is depicted on so many Icelandic drinking horns is one of the questions that researchers have not yet answered.

Stang believes St. Olav must have had a different status in Iceland than in Norway, and that the importance of his being a Norwegian king must have been experienced differently. “St. Olav was a popular saint across much of northern Europe, but I think there was a wide variation in how he was perceived. We might not have recognized the Olav that was worshipped in northern Germany, for example. The cult of saints had a stronger local stamp than we usually imagine,” she says.

Stang relates a story from one of the Icelandic bishops’ sagas, wherein Icelanders and Norwegians find themselves on a boat to Norway, discussing the saints. The Norwegians tell the Icelanders that their saints are too weak, and are of course “punished” for their harassment of the Icelanders. This saga “shows that the cult of the saints had many local and regional variants, and that they were important for local identity,” says Stang.