The toy boat that sailed the seas of time

A thousand-year-old toy boat from an abandoned water well gives archaeologists tantalizing clues about the culture that produced the object.

A thousand years ago, for reasons we will never know, the residents of a tiny farmstead on the coast of central Norway filled an old well with dirt.

Maybe the water dried up, or maybe it became foul. But when archaeologists found the old well and dug it up in the summer of 2016, they discovered an unexpected surprise: a carefully carved toy, a wooden boat with a raised prow like a proud Viking ship, and a hole in the middle where a mast could have been stepped.

The toy boat had a hole in the middle where a mast could have been stepped, allowing a child to sail the boat. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

“This toy boat says something about the people who lived here,” said Ulf Fransson, an archaeologist at the NTNU University Museum and one of two field leaders for the Ørland Main Air Station dig, where the well and the boat were found.

“First of all, it is not so very common that you find something that probably had to do with a child. But it also shows that the children at this farm could play, that they had permission to do something other than work in the fields or help around the farm.”

The story of a small farm

Finding a 1000-year-old Scandinavian toy boat is not that common, but it’s not that uncommon either. In fact, a similar boat, in both age and construction, was found in downtown Trondheim in 1900, when the road in front of what is now the Trondheim Main Public Library was dug up to install sewer pipes.

Ellen L.Wijgård Randerz (left) and Ulf Fransson, from the NTNU University Museum, look at a toy boat that archaeologists found in an abandoned well in Ørland. Randerz is the museum’s conservator, and Fransson was one of the field directors for the Ørland dig. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

The finds from the city at that time included a big spoon, different handles, pegs made of wood and “a little boat,” according to the acquisitions list. This particular boat is even on display at the NTNU University Museum.

But in the Middle Ages, Trondheim was already established as a trading post and a city, one that was the nation’s capital during the Viking Period until 1217. The concentration of people, and the wealth generated by trade almost certainly ensured that at least some children had the time and ability to play — and thus toys, like the boat, to play with.

The find from Ørland, however, is very different, says Ingrid Ystgaard, an archaeologist who is head of the entire Ørland Main Air Base project.

“The Middle Age farm here is far from the sea, it is not that strategically located,” she said. “There are other farms in Ørland that were better located.”

Thus, this medieval farm was probably not the richest farm in the area, far from it. Yet life here was good enough so that someone had time to carve the toy boat for a child.

And the child had time to play with it.

A really cool toy

Boats were among the most technologically advanced objects made in the Middle Ages, Fransson said.

A model of a knarr – exhibited in a museum in Hedeby, in northern Germany. A knarr was a kind of a freighter, and was broader and shorter than a Viking war ship. Photo: Wikipedia

“If you built a Viking ship or a knarr (a type of boat), both children and adults would have thought it was very important, it was very specialized construction,” he said.

“This is a ‘real’ boat. You don’t have to do this much work to make a toy for a child,” Fransson said. Whoever made it “worked to make something that also looked like a boat.”

A realistic looking toy boat would thus have been perceived as “really cool, just like kids today think that race cars or planes are really cool,” he said.

From bay to dry land

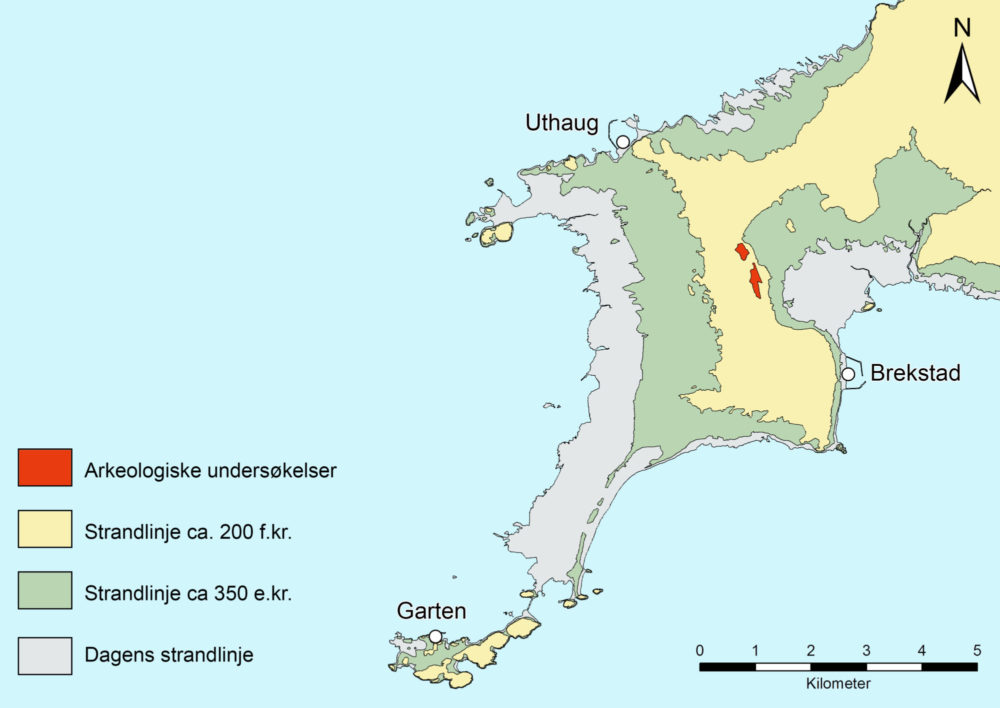

The map shows the location of the Ørland archaeological dig (red) along with approximate coastlines from different periods. The yellow shows the land area and coastline from 200 BC, the green shows the land area from roughly 350 AD and the grey shows today’s coastline. Map: Magnar Mojaren Gran

One of the things that archaeologists find most fascinating about the entire Ørland project has to do with the location of the dig itself.

Ørland is a rectangle of land on Norway’s outer coast that looks like the head of a seahorse jutting into the Atlantic Ocean. But it didn’t always look this way.

Consider this: Norway was once covered with kilometres of ice during the last Ice Age, more than 13,000 years ago. The great weight of the ice sheet depressed the land it sat on. After the glaciers disappeared, the land has gradually risen up, or rebounded.

An overview of the Ørland dig where the boat and shoes were found. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

This rebound created many changes along Norway’s coast, most notably when land that was once an island rose up and became a part of the mainland, or an area that might have once been a shallow bay became dry land.

Ørland is one of these places. In roughly 200 BC, during the Iron Age, Ørland’s big chunky peninsula looked more like a thin curled finger, with a big bay trapped on its southern side. Now that bay is dry land, nearly 2 km from the coast.

The Museum’s single largest dig — ever

Fortunately for the NTNU archaeologists, the Iron Age seaside location is precisely where the Ørland Main Air Base decided to expand its facilities to accommodate the purchase of new F-35 fighter jets, approved by the Norwegian Parliament in 2012.

This worn-out sole tells archaeologists that the owner was willing to pay to repair his shoes, since the front of the sole is clearly cut off. The size of the heel suggests the owner was probably male and had fairly large feet. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

The expansion plans triggered the need for an archaeological investigation. By the end of the 2016 field season, the NTNU University Museum had excavated nearly 120,000 m2, or roughly four times the size of a good-sized shopping mall, over three summers of fieldwork.

This makes it the single largest archaeological dig undertaken in the history of the museum.

Seven farms, 1500 years

Ørland’s fertile soil and strategic location near the mouth of Trondheim Fjord have ensured that people have lived in this area for millennia. So it should come as no surprise that the extensive dig uncovered traces of seven farms, spanning 1500 years, from 500 BC to 1000 AD.

The farms and farmyards are marked by postholes from structures, garbage dumps, and old wells. These Ørland farms, clustered as they are in one place, tell a unique story of how farming and farm communities evolved in the region over 1500 years, Ystgaard said.

“This is one of the biggest questions we are studying, the development of farms in this area over a span of 1500 years in the past. It is fantastic material,” she said.

Dating Norway’s historic past

Archaeologists date early history based in part on when different materials came into use in different parts of the globe. Here's what that looks like in Scandinavia:

- The Stone Age dates from just after the glaciers left, about 10000 BC, to 1700 BC

- The Bronze Age dates from 1700 BC to 550 BC

- The Iron Age dates from 550 BC to 800 AD

- The Viking Age dates from 800 AD to 1030 AD

- The Middle Ages (or Mediaeval period) dates from 1030 AD to 1537 AD.

Garbage, seeds and pollen

While the field portion of the dig is now completed, archaeologists will continue to work their way through samples they’ve taken from garbage middens and cooking pits, and sift through dirt that has been removed from house and fence postholes.

A team from the University of Bergen is also hunting for clues about the vegetational history of the area based on pollen in cores they’ve taken from a nearby wetland called Stormyra.

The garbage middens and cooking pits, with their animal and fish bones and seashells, shed light on what people ate.

The dirt from the postholes offers a different view of daily life. Seeds and grains that have fallen on the ground tend to collect or be swept into corners. That makes postholes a treasure trove of information about the kinds of grains inhabitants ate or grew.

And lastly, by looking at changes in pollen types and amounts over the centuries, based on the cores collected in a nearby wetland, the researchers can reconstruct what the vegetation around the farms was like from the last 2500 years.

They should be able to detect changes caused by grazing animals, logging and farming, of course.

All of these puzzle pieces help to fill in the many unknowns about how rural farms operated over the millennia, particularly during the Middle Ages, Ystgaard said.

“We know very little about the organization of farming in Norway in 1000 AD,” Ystgaard said. “We have investigated almost no farms in rural communities in Norway from this time.”

But with the wealth of information collected from Ørland, “we can look at the social development of farms during this period.”

Shoes that date from St. Olav’s reign as king

One of the most complete shoes from this time period found at the Ørland site. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum

The well that yielded the toy boat and a second well contained other treasures, including pieces of leather that might amount to four leather shoes. The high water table in the filled wells helped preserve the shoes and the wooden boat.

If any of these objects had been discarded in a drier area, they would have probably decomposed, said Ellen Wijgård Randerz, a conservator at the NTNU University Museum who has responsibility for the artefacts from the project.

When the shoes were first discovered, the researchers thought they must be from more recent times than the Middle Ages, she said.

But when the radiocarbon dating information came back, it was “big news,” said Ystgaard. “We found shoes that are contemporaneous with Olav den Hellige,” who was king of Norway from 1015 to 1028.

Walking in their shoes

Finding the shoes —which look a little like moccasins, with a leather sole and simple, form fitted shape — also tells the archaeologists that the farm was not that wealthy.

“These were more of an ordinary shoe, a work shoe that they wore every day,” Fransson said. One of the shoe pieces that was found was a heel piece from a large sole, with a hole worn through it. The clean-cut front edge of the heel piece shows that “the shoe was worn out and they did repair it,” he said.

But because the researchers found much of a whole shoe, “that tells me that they weren’t that poor either, because they had the means to throw (a whole shoe) out,” he said.

The shoe had been cut to fit the individual’s foot and probably fit reasonably well, Randerz said, but people today probably would find it thin, cold and slippery.

“They might have stuffed the shoes with grass, and worn thick wool socks, but they were definitely not warm or dry,” she said, studying the shoe. “It says a little about what it was like to walk in their shoes.”