MazeMap navigates the world

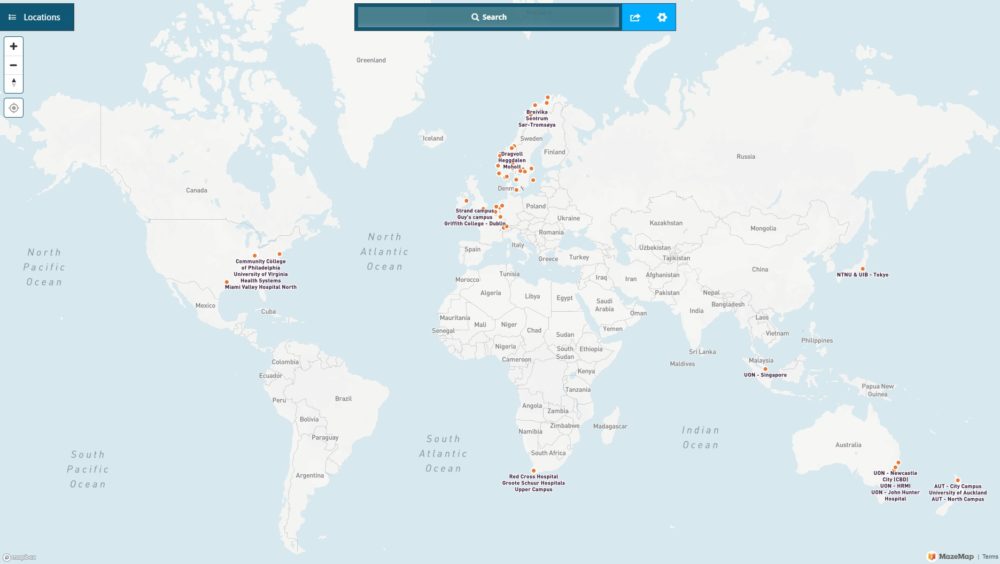

The map app started by getting students where they needed to go in Trondheim. Now MazeMap is showing people the way on five continents.

MazeMap is a detailed digital mapping service that shows you how to get to the room you’re looking for in buildings you are unfamiliar with.

“The goal now is to double our sales each year,” says Thomas Jelle, CEO of MazeMap. Today, the company has 27 employees.

It all began rather quietly with a master’s thesis at NTNU ten years ago.

Professor John Krogstie, Jelle’s advisor at the time, recalls that Jelle the student did very well. He earned the grade of “A”. Krogstie now heads NTNU’s Department of Computer Science.

No one back then had any idea what a simple navigation service for buildings could develop into, and almost everything has changed in the years since.

“We’ve really just kept the basic idea,” Jelle says – that is, a wayfinding tool to help people locate places in large buildings and campuses.

Campus Guide

Initially, the service was called Campus Guide, and it was designed to help students navigate the campus at Gløshaugen in Trondheim. Here the buildings are spread over a large area and the number of rooms confuses even people who have been here for years.

The digital mapping service makes it easy to locate where you want to go. Simply look up the room number on MazeMap, either on your mobile or your PC.

“Some of the secret lies in MazeMap’s simplicity,” Krogstie says.

What do you want to do? Well, you want to find a room. What do you see when you look up a room number? Where the room is located. And – happily – little else.

Other people thought MazeMap sounded convenient and simple as well.

Outward from Trondheim

Eventually, the service was extended to other parts of NTNU and to St. Olavs Hospital, and then out of town.

“MazeMap is now available at all the Norwegian universities except one,” says Jeanine Lilleng, technical director and delivery manager for the company. Her job is to keep track of all the details in a rapidly growing company.

The map service has also been implemented at universities in Sweden, Denmark, England, The Netherlands, USA, South Africa, Singapore, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Australia and New Zealand.

“We sell primarily to universities, hospitals and private companies,” says Jelle.

These are usually big players who need a mapping service they can trust and who may think that they can profit from it as well. Jelle has a good example.

“At St. Olavs Hospital, 2.9 per cent of patients missed their appointments. After the hospital adopted MazeMap, the missed appointments decreased to two per cent.

This means that the hospital saves about NOK 14 million a year. The decline may well have several reasons, but patients now receive a map link in their text reminder ahead of their appointment.

The staff at MazeMap has increased by 30 per cent within the past year. Lilleng believes that part of the reason the company can finally surge ahead now is that Jelle has been patient and allowed MazeMap to mature over several years.

Article continues below photo.

Wireless Trondheim

The map service started out as a small part of the Wireless Trondheim initiative, a collaborative effort between NTNU and local authorities and industry. The city received 120 wireless hotspots that covered large parts of the city centre and enabled around 5 000 people to connect to the free wireless network simultaneously.

Residents acquired a handy wireless network. It also became a laboratory to test new apps and mobile services, such as was what would eventually become MazeMap.

In 2013, the mapping service became a separate company. MazeMap still has its headquarters in Trondheim, but also has employees in Palo Alto, California, London and Melbourne.

- You may also like: Improve your Norwegian with tailor-made language app

Still collaborating

MazeMap and NTNU are still collaborating closely. The most recent example is a Research Council of Norway project where MazeMap and NTNU looked at how buildings can be made more accessible for everyone, and how AI techniques can be used to more effectively keep the maps updated.

MazeMap depends on its maps corresponding to what’s on the ground. Buildings are renovated all the time, and it is important for the maps keep up with those changes.

“Between 5 and 10 per cent of the buildings change every year,” says Jelle.

So some maintenance will always be involved. It’s stupid to direct someone to a room that does not exist, or now has a different name, or perhaps a room with the old name has now moved to another part of the building. Details like these need to be checked all the time, so automating major parts of the process is useful.

The story of MazeMap basically demonstrates how researchers, educational institutions and business people can work together.

“This is a mobile service that became the basis for innovation,” says Krogstie, who recently presented MazeMap to NTNU leaders and Norway’s Minister for Science and Higher Education as an example of how successful projects can be with effective collaboration.

“NTNU is good at making the transition from research to commercialization, but different people are good at different things. Good researchers aren’t necessarily the best people to charge with commercializing their research results. It’s important to partner with people and groups who can think more commercially,” says Lilleng.

MazeMap on YouTube: