Putting insects on the dinner table

Norwegian students want to start farming and selling insects as food. But it may take some time before Norwegian families begin to include grasshoppers in their Friday night dinners.

The words “food” and “insects” are not used in the same sentence very often in Norway, but if NTNU students Victoria Stokke and Ida Hexeberg Rustad get their way, this may change in the future.

Victoria Stokke, a student at NTNU, would like to make insects a more normal part of the Norwegian diet. Here, she shows us a few edible grasshoppers. Photo: Myldregard

The two women want us to start eating insects the same way we eat, meat, salad and pizza, and the same way it is completely normal to eat dog in Vietnam.

Waiting for the go-ahead

The students are working with a company called Myldregard to be able to import edible insect products. Their end goal is farm insects for consumption in Norway. The first step is to introducemealworms to the Norwegian palate.

Currently, they are waiting for approval from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. EU regulations require an application process that can take anywhere from five to 17 months.

- You might also like: Food waste recycling is not always the best idea

Weird for us, quite normal for others

In certain countries, it is completely normal to eat different insects, but in western societies, we tend to see it as unpleasant and disgusting. However, in countries such as Thailand, China, Japan, Ghana, Australia and Mexico, insects are just another part of the diet. The Netherlands is also starting to introduce insects to their national dishes.

Facts about eating bugs

Entomophagy: the scientific term for consuming insects.

In many Asian and African countries, insects are a prime source of protein.

In western society, eating insects is uncommon, and generally somewhat taboo.

It takes almost tens times as much plant food to produce 1 kg of meat as it does to produce the same amount of food from insects.

Although Norwegians have a somewhat more uncomfortable relationship to bugs, there are a lot of good arguments as to why we should start eating them, from nutritional value, to climate friendliness, to taste.

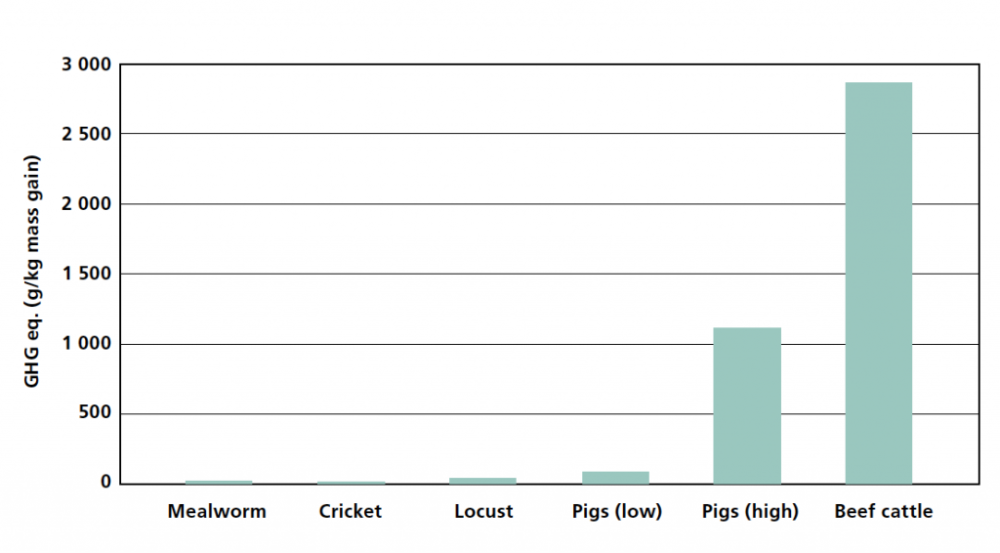

Several of these arguments come from a 2013 report published by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, where it was concluded that significantly less greenhouse gases are emitted from producing 1 kg of mealworms than in producing the same amount of meat.

The story continues under the graphic.

Cattle emit the most greenhouse gases in terms of food types. Insects, however, are positively climate friendly. Mealworms and grasshoppers contribute almost no emissions. Photo: FAO

Insects are rich in protein

When it comes to nutritional value, there’s no question— insects are rich in protein, something that we Norwegians usually get primarily through meat. In addition, eating insects is very climate friendly, especially compared to the modern meat industry.

- You might also like: Save the planet, stop eating meat

But what about taste? Generally, insects, when properly prepared, can be just as tasty as ‘normal food’. They can even be a kind of delicacy, if the experts are to be believed.

“Originally, I thought of eating insects as a way to get animal proteins in my diet in a more ethical manner. Now, I see it as a tasty, exciting way to vary my diet,” says Stokke.

We learn our food habits young

What do we have to do to make this a trend? What do we need to do to make insects go from something that are seen as vile, to a tasty treat?

Social psychologist Christian Klöckner explains that insects are not something that we are naturally repulsed by as children.

“Children have no problems with eating insects. They’re naturally curious and generally find insects to be interesting. But adults quickly teach them otherwise,” says Klöckner.

Christian Klöckner is a professor of social psychology and quantitative methods at NTNU’s Department of Psychology. Photo: NTNU

When children learn something at an early age, it sticks with them. When it comes to our views on insects, we’re talking about years and years of trained attitudes.

“Changing our opinion on something that is generally seen as gross is a long process,” he says.

But is it at all possible? Yes, and the key is creativity.

Research shows that children are much more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they have fun names. A seven-year-old would much rather eat a plate of “Batman’s super-fuel” than a plate of broccoli.

Appearance isn’t everything, but…

According to Klöckner, the same tactics might work well when it comes to eating insects. If you give a food product a cool, catchy name, people will be much more likely to try it.

Changing the name may make things easier, but it won’t help if there are still uncooked worms, ants and larvae on your plate.

Klöckner thinks that changing the appearance is important as well, to make the insects more appetzsing. How about larvae chocolate that just looks like a normal candy bar? Or grasshoppers that look like French fries?

Spreading innovation

Another challenge is that food and identity are strongly connected. Klöckner explains that he never sees as many strong reactions as when it comes to studies about our eating habits.

“It may be seen as an attack on our identity, so I doubt that insects will become a central part of our diet,” Klöckner says. That doesn’t mean that he isn’t for the students’ project, however.

“Food is one of our largest expenses when it comes to resources, and food production contributes a huge amount to greenhouse gas emissions. Working with alternative food sources is important,” he says.

Take a tour of Victoria Stokke’s mealworm farm (in Norwegian):