The church revolution that changed Europe

Five hundred year ago, Martin Luther’s 95 Theses sparked the Protestant Reformation. He had no idea how quickly his ideas would spread and change Europe.

In 1517, no one could predict the consequences of the Reformation. The Lutheran Reformers didn’t intend to split the Church. They just wanted to modify some of the practices in the Roman Catholic Church.

The Reformation

• On 31 October 2017, it will be 500 years since the Protestant Reformation began, when Martin Luther made public his criticisms of the Catholic Church.

•Gemini Research News is marking this anniversary with several articles about the Reformation.

•Professor Ola Tjørhom has edited the book Reformasjonen in nytt lys [The Reformation in a new light] with Professor Tarald Rasmussen at the University of Oslo. Religious movement researchers Arne Bugge Amundsen, Aud Tønnessen and Hallgeir Elstad also contributed to the book.

But Luther’s decisions from 500 years ago continue to affect us today.

“This wasn’t just a gossipy, religious, ecclesiastical matter. It led to new developments,” says Ola Tjørhom, professor Dr. Theol. at NTNU’s Department of Teacher Education.

Luther was a professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg in Germany and a Catholic monk. In the fall of 1517 he authored 95 theses, or doctrines, criticizing certain ecclesiastical practices. Finally, on 31 October of that year, Luther sent his theses to some friends, to the bishop of Brandenburg and to the archbishop of Magdeburg and Mainz.

It was time

According to his ally Philipp Melanchthon, Luther also nailed the theses on the church door in Wittenberg, although no eyewitness account exists. Either way it would have been a fairly common discussion practice, and not particularly noteworthy.

Luther sets fire to Pope Leo X’s Bull of Excommunication. Several Catholic writings are added to the fire simultaneously. December 1520. Illustration: Matthäus Merian the Elder, Thinkstock

These theses caught on so quickly that large parts of Europe embraced Luther’s teachings and practices within a few years.

But why on earth did it happen so fast?

“In short, people wanted a new religion,” says Tjørhom.

The beginning of the 1500s was not exactly blessed with talented popes. “Several of them appear on lists of the ten worst popes ever,” Tjørhom says drily.

Alexander VI, Pope Leo X and Clement VII all belonged to some of the most powerful families in Italy. They rarely got good reviews, were not particularly pious and many of the faithful were sick of having corrupt, profligate and power-hungry men as leaders of the Catholic Church.

Buying your way out of sin

At this time the indulgences trade had become commonplace. This practice was one of the things that irked Luther the most, and many of his theses are attacks on indulgences.

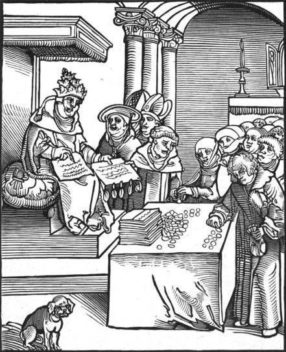

The Pope as the Antichrist, signing and selling indulgences. Propaganda drawing by Lucas Cranach the Elder, commissioned by Martin Luther.

Indulgences were really a remission of punishments that were imposed on people who had committed different sins. This penalty could be atoned through actions on Earth or by spending time in purgatory before finally entering Heaven.

More commonly, however, this punishment was served by paying earthly money to the Church or through special traders, even though indulgence monies were officially referred to as “donations” by the leading powers in Rome.

The trade in indulgences was also controversial within the Catholic Church, but it was considered essential to finance the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica and involved very large sums. Although the selling of indulgences was completely banned in 1567, the Catholic Church still maintains the notion of indulgences.

You may also like: Indulgence trading was big business before the Reformation

Growing awareness

“This was also a time of increased awareness among the bourgeoisie,” says Tjørhom.

Bourgeois urbanites read books, which had become far more accessible to people in the decades since Johann Gutenberg’s Bible was printed in 1455.

Tjørhom believes Luther was a master at exploiting the art of printing. This helped to spread his message quickly. Luther had pamphlets and sermons, table talks and heavy papers printed up that people devoured. He was enormously productive, and the so-called Weimar Edition of Martin Luther’s writings is one of the world’s most voluminous works.

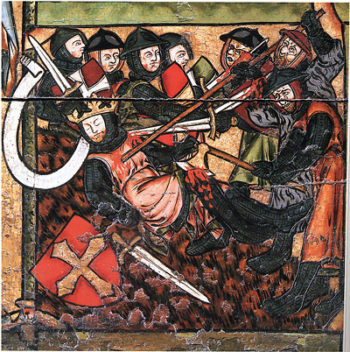

But upheavals in church services were at least as massive.

With the arrival of Martin Luther, the church congregation became important participants in the liturgy, resulting in more exciting Masses for many. Right side of illustration shows the Pope’s Descent to Hell. Illustration by Lucas Cranach the Younger

Woke the sleeping

Luther believed that the faithful should participate actively in worship. The congregation was simply the most important part of worship. The common Catholic practice at this time, by contrast, showed little regard for the congregants at all.

“The priest often stood at the altar and mumbled, since what he said was between him and God, and didn’t concern the laity,” says Tjørhom.

Meanwhile, churchgoers sat on their benches, perhaps without really hearing. This would hardly have made a big difference for them anyway, since the service was held in Latin, a language that very few people understood. Services couldn’t have been exactly exciting most of the time, despite the music and splendour.

Sometimes priests even held so-called private Masses without an audience, usually for the deceased, where the priest read to empty benches.

Luther wanted none of that. Instead, he thought parishioners should join in singing hymns, and sermons should be held in a language that they could understand.

“Luther was an exceptionally good preacher. People flocked to hear him preach. In Catholicism, sermons played only a minor role. It was the liturgy that counted,” says Tjørhom.

Luther translated the Bible into German and in this way enabled people to read and understand what was in it. Luther’s German Bible was crucial for the German language.

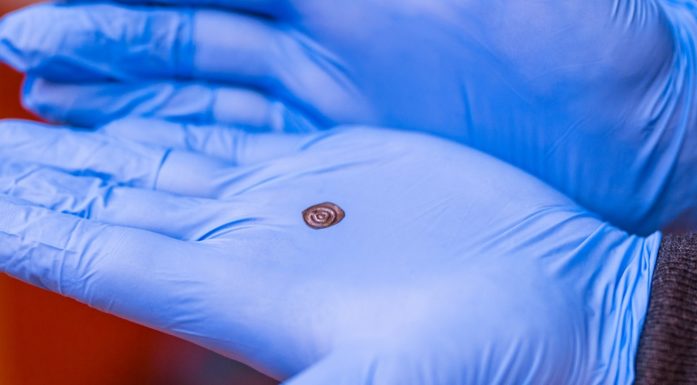

We don’t know what Olav Engelbrektsson looked like, but this is his Seal with a portrait of St. Olav. Illustration: Wikipedia, Norway churches in the Middle Ages

The time was ripe for change. Many Europeans jumped at the chance. But certainly not all.

In Norway, the Reformation took time to take hold

The Reformation had little popular support to begin with and was slow to take hold in Norway, says Tjørhom. “People lived as Catholics until well into the 1600s, especially in rural areas.”

The Reformation was officially introduced in 1537, when Olav Engelbrektsson – the last Roman Catholic Archbishop in Norway – had to flee the country as the king’s troops approached his last base at Steinvikholm castle in Trøndelag county. But the Reformation gained only limited acceptance in practice. Church life continued more or less as before in large parts of Norway.

In a sense, one could say that popular involvement in Lutheranism did not take off until the ideas of the lay preacher Hans Nielsen Hauge revived the faith in the first half of the 1800s. This came about 250 to 300 years after the spread of the Reformation in Germany. Hauge’s brand of Lutheranism was distinctive, inspired by the Low Church and pietism.

You may also like: The archbishop’s mint

Lacked reformers

This slow change had several reasons. Norway was at that time undoubtedly a backwater and did not have particularly good contact with the rest of Europe. But that alone does not explain why the Reformation was embraced more slowly here than further south.

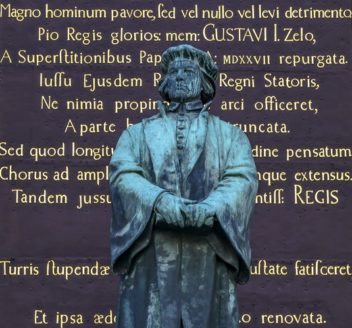

Olaus Petri was a clergyman, writer, and a major contributor to the Protestant Reformation in Sweden. By his own account, he barely escaped the Stockholm Bloodbath in 1520. Photo: Thinkstock

Tjørhom suggests that one reason was probably the lack of leading reformers in Norway.

Denmark had several reformers, including the former friar of the Order of St. John, Hans Tausen. Finland had the esteemed Mikael Agricola. Sweden eventually had the brothers Olaus and Laurentius Petri, although the bloody battle over the liturgy and church order dragged on until 1593 before the was over. But Norway had no such leading reformers.

The occupier’s Reformation

Another important reason why Luther’s ideas made limited headway was that the authorities in Copenhagen acted cautiously in Norway in the early years of the two countries’ union. Norwegians were grumbling, and Denmark saw little point in forcing anything more on them.

“The Reformation was seen by many as part of the Danish occupation,” says Tjørhom.

King Christian III reigned in Denmark and Norway at this time. He had political reasons to reform Norway, but these were probably not his driving motivation. The king also supported the Reformation for personal reasons, and he had met Luther at the Diet of Worms in 1521.

“So the Reformation was largely a political decision, not just a religious one. Christian III was a devout Lutheran and was German by background and in his political mindset. His 1536-1537 political coup was in many ways consistent with the North German political tradition,” says Professor Erik Opsahl at NTNU’s Department of Historical Studies.

But none of those factors increased the enthusiasm in the north, and no popular movement took hold. On the contrary, Norway’s continued political independence within its union with Denmark bound it to the Catholic Church. The Church had the best-developed administrative system in Norway and provided people with the most services.

The Olav tradition was strong in Norway. It took several hundred years before people stopped their Catholic ways of living and worshipping. Photo: snl.no

You may also like: Icelandic drinking horn changes our understanding of St. Olav

Inextricably linked

Olav Engelbrektsson fought for Norway’s political independence within the Union, which also implied a defence of the Catholic Church’s position in the country. Political developments in 1537 had led to Norwegian political independence and the Catholic Church being inextricably linked. Debating whether Olav Engelbrektsson was really fighting for the Catholic faith or Norwegian independence, as is often done, is therefore meaningless.

“Once the king gained control over Norway, he failed to fulfil his promise to make Norway a Danish province. The country remained a separate kingdom, but the abolishment of the Norwegian Council stripped Norway of its political influence in the union and made it subject to Danish rule,” says Opsahl.

The Danes also tried to destroy the strong Catholic Olav tradition in Norway, which was so closely connected to Norwegian identity, social community, tradition and culture. These were all aspects of the cult of St. Olav. The Danes even went so far as to melt down the silver in St. Olav’s shrine, which supposedly contained the remains of the Saint-King.

“A few year’s after Olav’s body was laid in a new tomb in the cathedral in 1564, the grave was obliterated at the king’s behest, and has never been found since,” says Opsahl.

That may well be why it took so long to bring the Norwegians around.