When Vikings didn’t rely on mobile money transfers

What is money exactly, and what’s the connection between modern-day mobile money transfers and the larger-than-life Viking Halldórr?

Haraldr Hardråde – known in English texts as Harald III Sigurdsson, with the epithet “the Ruthless” – was said to be a strong-willed and brutal guy. He was Norway’s king from 1046 until he was killed in the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Murder and bribery no doubt contributed to his hold on power. He liked to surround himself with others of the same tough calibre – and then some. This story can be found in the Old Norse kings’ saga Morkinnskinna:

What is the similarity between these two things? The Vikings mistrusted the coin at the top, while some individuals might also mistrust the Norwegian mobile money transfer service called Vipps. But citizens have needed to trust both in their time. Illustration: Steinar Brandslet, NTNU

The Icelander Halldórr Snorresson was one of the toughest men in the king’s army, a faithful and long-serving warrior in Byzantine, with lives on his conscience. On the eighth day of Christmas, the soldiers were to receive their wages in the form of the king’s silver coins. But around this time the coins were already being minted with a large proportion of copper.

Halldórr held his pay on a flap of his cloak. The silver coins didn’t look pure. With a swipe of his other hand, he scornfully scattered them all onto the ground and said,

“Why should I serve the king any longer when I don’t receive my payment in pure silver?”

Halldórr refused the king’s coins. He wanted real silver, but it didn’t help that other servants of the king accepted the coins as payment. Nor was Halldórr swayed by warnings that the king would see it as an insult if his long-time servant did not accept the coins.

“Never have I been so deceitful during my service to him, as he was when he paid me,” Halldórr told Bård, the king’s envoy.

Bård brought this message to King Harald and asked for Halldórr to receive payment in the form of “good silver”. The king initially thought that this was unreasonable, but Bård then asked if Halldórr’s courage, their long friendship and the king’s generosity were not reasons enough to make an exception. At the same time he reminded the king of Halldórr’s “contentious disposition,” which probably meant something quite different at that time than it usually does now.

“Give him the silver,” said Harald the Ruthless.

One of Norway’s strongest rulers acceded to Halldórr’s demands. But why did he insist so vehemently, when it could have cost him his life? Didn’t he trust the king and his currency?

- You might also like: Beer and a calf’s head yield gold and silver

Trust and power are prerequisites

Halldórr was a foreigner in Norway. He was returning to Iceland, says Jon Anders Risvaag, an associate professor at the NTNU University Museum.

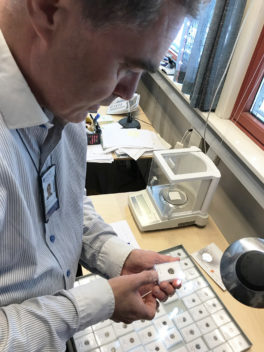

Risvaag is the museum’s numismatist, or currency expert, and believes he may understand the reason for the Viking’s aversion to the king’s impure coins. Money has always been dependent on two things.

“You need confidence in the payment method and a central power apparatus that can guarantee it,” says Risvaag.

You need confidence in the payment method and a central power apparatus that can guarantee it,” says Jon Anders Risvaag. Photo: Steinar Brandslet, NTNU

From early times, a coin’s value was linked to the amount of precious metal in it. Foreign silver coins were used in Norway long before minting started there in 995, and the silver content was more than 90 per cent.

But under King Harald, coins were minted with steadily less silver, down to as little as 30 per cent. This was a way for the king and his administration to save and earn money. At the same time, the central authority would guarantee that these coins were worth as much as before.

The king’s word was perhaps good enough in Norway, and there the money could readily be used as a means of payment. The king himself vouched for the coins’ legitimacy despite the decreased silver content, and his power apparatus made sure that the people followed the king’s decrees. Big protestations weren’t a good idea, either.

But once back home in Iceland, Halldórr couldn’t count on people to accept coins with lesser amounts of the precious metal. There it was weight of the silver that mattered, not the king and his people far away on the mainland.

So what does this mean for us today? Quite a lot, actually. Trust and power are still the basis for a currency’s value.

- You might also like: The archbishop’s mint

Electronic money and impure coins

When you sell tickets to support the school band and accept an electronic money transfer as payment, you’ve actually assessed the situation in the same way Halldórr did. The difference is that you arrived at a different conclusion – you trust that the transaction will go through with no problems. Which is usually the case.

Norwegian authorities have decided that the Norwegian krone (NOK) is legal tender in Norway, where you even trust the banks as intermediaries, and the banks can no longer just fail. State power and guarantees support the law.

Physical cash has largely disappeared and has been replaced by numbers in our accounts.

The use of mobile electronic payment services like Vipps has merely extended our disconnection from physical money. This is a natural development, says currency expert Jon Anders Risvaag. Photo: Colourbox

That might beg the question whether we lose anything by exclusively relying on electronic money transfers?

Risvaag doesn’t think so. “We’ve already lost anything that could have been lost. This is simply an extension of disconnecting from physical means of payment. It’s a natural development,” he says.

Coins and banknotes are on their way out. There aren’t nearly as many physical means of payment as there is money in the world.

Even the currency expert hardly carries any cash anymore.

“It’s almost embarrassing, but I even pay small bills with my bankcard,” he admits.

That’s how a lot of people in Norway pay for things. But not that long ago everything was different.

- You might also like: The church revolution that changed Europe

In the beginning

Risvaag’s father grew up in Norway’s far northern Finnmark county. He was a teenager in the 1930s and trekked over the mountain with sheepskins to pay the bill from the merchant. Older people still remember that time.

But not too many people do this anymore. Money has replaced barter.

“Money and coins are an abstraction,” says Risvaag.

Money has never really had any value of its own. It has always been a symbol of something else, like fish, a pregnant ewe or the value of work done.

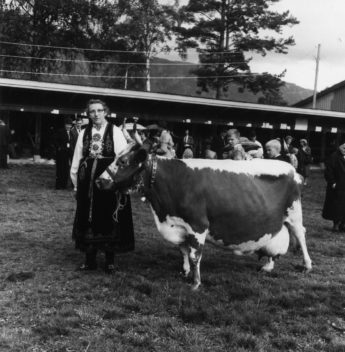

We don’t bring the cow and the calf with us to the market to exchange for some pigs anymore. Instead, we use money.

We don’t bring the cow and the calf with us to the market to exchange for some pigs anymore. Instead, we use money. This photo is from Dyrskuplassen in Seljord municipality in 1967. Photo: Regional State Archives of Kongsberg, National Archives

“Some of the earliest coins had pictures of the animals they symbolized the value for,” says Risvaag.

The first coins we know of appeared in Turkey, Greece, India and China around 700-600 BCE. They were an extension of metal bars, shells, knives and other means of payment that were also symbols of the value of something tangible.

Some of the earliest coins had pictures of the animals they symbolized the value for.

Money as the basis for cities – and vice versa

In turn, this abstraction has formed part of the foundation for advanced civilizations. Money and the development of cities have gone hand in hand.

Can you imagine residents dragging around animals, furs and fish to swap for vegetables, woven fabrics or a new mobile phone in our modern cities of millions? Could be just a bit awkward, perhaps?

You can also see the opposite influence. The emergence of larger, more complicated societies required residents to have different ways to pay than by exchanging goods.

Cash hasn’t met its demise yet

Early on we used coins, then also paper bills. Many Norwegians received their salary in the form of cash in a bag until about 1980, and some even longer. Next, we queued in front of the ATM to withdraw cash we could use in stores before we finally were able to use the card in stores and in taxis.

The shift from barter to electronic money transfer services — in Norway, the most common one is called Vipps — has happened incrementally. Long ago, we took the abstraction a step further than cash and reduced values to numbers we move around.

“Norway is extremely far ahead in this area. Even Sweden has more cash in circulation,” Risvaag says.

But he still doesn’t see the demise of coins and banknotes any time soon, at least not in all realms and in all societies. They are still necessary for several reasons.

In Germany, a large majority of the population – close to 80 per cent – still uses cash to shop in stores. This rate is the highest in Europe, and is probably due in part to Germany’s special history. Their experiences with a strong state have not been all good.

“Most Germans don’t want to be monitored,” says Risvaag.

Because when you use your bankcard, someone always has an opportunity to find out about you, a bit like when you use your mobile phone.

Scepticism about forms of payment, government and power still exist, just as it did for Halldórr. But nowadays we rarely protest as vehemently anymore.

Source:

Jon Anders Risvaag: Mynt og by. Myntens rolle i Trondheim by i perioden ca. 1000-1630, belyst gjennom myntfunn og utmynting [Coin and city. The coin’s role in Trondheim in the period approx. 1000-1630, explained through coin discoveries and minting]. PhD dissertation, Trondheim, October 2006. https://www.academia.edu/363300/Mynt_Og_By