Nepal tests maternal education designed by NTNU students

Nepal ranks high in maternal and child mortality statistics. A study trip to the mountain country inspired several NTNU students to help improve the situation of Nepali women.

After their study tour, the students joined forces to write a master’s thesis in industrial design. Their maternity care project in Nepal was recently selected from among the finalists of the International Service Design Award 2019 (Students).

Ida Christine Opsahl, one of the project’s students, said, “We wanted to design meaningful solutions for people who don’t have the same opportunities as we do.”

Local contacts

NTNU Professor Martina Keitsch also teaches at Tribhuvan University in Nepal and helped the students get in touch with local actors. The students began a close collaboration with the aid organization Green Tara Nepal. Although the Nepalese government has a protocol for basic maternity care, less than twenty per cent of women receive this care.

“Many women give birth at home and receive no follow-up care other than what their mother-in-law or other women can provide.”

Postpartum follow-up care is particularly poor in the districts where eighty per cent of the population lives.

- You might also like: “Beeting” high altitude sickness with beet juice

Co-created materials

The students interviewed local health experts and women from 14 to 76 years old as part of their strategy to understand the situations in the capital Kathmandu and in the village of Tasarpu. They also received valuable help in their work from an interpreter and a health worker from Green Tara Nepal who had local knowledge and knew the women’s challenges well.

Emphasis was placed on including local experts and health professionals in the project and on co-creating services and informational material.

“It’s not every day that a master’s thesis leads to concrete measures, but in this case the good ideas won’t just end up in a drawer.”

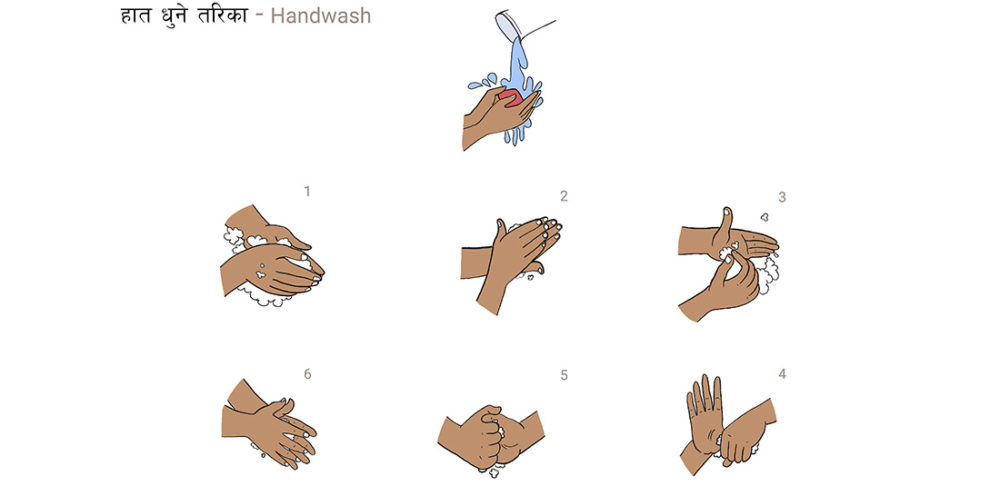

Due to high illiteracy and many local languages, the students focused on using as many illustrations as possible and spoken language in the informational material. The illustrations were developed by testing them on new parents and collecting feedback to learn what made the most sense for the women.

- You might also like: C-sections by trained health officers a safe alternative

The first week

In their master’s thesis, the students designed a new health service for home visits in the first week after childbirth for women who are not able to travel to a health centre. Most critical complications occur during this period.

The service consists of a protocol for what should happen during the home visits, a spiral notebook and an illustrated brochure for the woman and the family that conveys important information about the postpartum period.

Some pages from the brochure:

Here are several pages from the brochure compiled by NTNU students. It includes information on how to breastfeed and care for the infant, vaccination, and symptoms of illness to watch for in mother and child. The information is mainly presented using illustrations.

“It’s not every day that a master’s thesis leads to concrete measures, but in this case the good ideas won’t just end up in a drawer.”

“Green Tara Nepal will be helping to implement a pilot project in Tasarpu soon, which is a typical Nepali village. The services have the potential to be scaled up for use in other villages and in other parts of the country,” says Nora Pincus Gjertsen, one of the master’s students.

Numerous obstacles

Students and locals conduct a group interview with women from a slum area in Kathmandu. Photo: Nora Pincus Gjertsen

Nepal has a long tradition of girls often getting married early, sometimes as young as 12-13 years of age, the students say. After marriage, it’s common for the young brides to move in with their husband and his parents – where they end up at the bottom of the family totem pole.

Early and frequent pregnancies increase the health risks. The society is strongly patriarchal with big social divisions.

The reasons many women don’t seek help following childbirth are numerous and complex. Great distances, a lack of independence, education, financial problems and cultural traditions all play a role.

Many women give birth at home and receive no follow-up care other than what their mother-in-law or other women can provide.

Complications like uterine prolapse and bleeding often occur, and mortality is high.

Women considered “impure” after childbirth

The NTNU students also encountered traditions that are not compatible with good maternity care. Limited information and a lot of superstition around the body and birth are still prevalent.

New mothers may be required to return to hard physical labour shortly after childbirth and are considered to be unclean during the postpartum period. In extreme cases, the students were told, the mother and child are made to stay outside the home in unsanitary conditions, such as with the farm animals.

Sorting ideas and developing the concept. Pictured: Julie Nyjordet Rossvoll (on left) and Nora Pincus Gjertsen. Photo: Ida Christine Opsahl

A better world

The three master’s students feel they’ve done a good job of upholding the NTNU motto.

“We definitely think our project is about knowledge for a better world,” says Julie Nyjordet Rossvoll, the third student in the master’s thesis.

“The process has been incredibly rewarding and has given us so many new perspectives. It’s fantastic that what we created is being used in practice. Our dream is that it can reach the national level and make a real difference for women and newborns in Nepal,” she says.

Maternal mortality in Nepal

Maternal mortality is very high in Nepal. In 2015, 258 women per 100 000 live births died. The mortality rate of newborns is also very high at 28 per 1000 births. In comparison, maternal mortality in Norway is 5 out of 100 000 live births and newborn mortality is 1.6 per 1000 births.

One of the UN's sustainability goals is for maternal mortality in all countries to drop below 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030 and for newborn mortality be reduced to 12 per 1000 births.

The postpartum period is considered to be the first six weeks after childbirth.