Pandemic has revealed our dependence on migrant workers

Food production was quickly declared a socially critical function with the outbreak of the pandemic. The dependence of agricultural and food industry sectors on migrant workers has never been clearer, one researcher says.

The coronavirus has taught Europeans an important lesson.

“The pandemic has shaken the entire system. Migrant workers weren’t allowed in. Production dropped and people were afraid that the fields wouldn’t be sown or harvested. A number of steps were taken to limit the effects, including separate entry rules for agricultural workers. This demonstrated the important role of migrant workers in the European food industry,” says Johan Fredrik Rye, a professor in NTNU’s Department of Sociology and Political Science.

In Norway, the state wanted to stimulate farmers to entice domestic labour to take on the spring planting and fall harvesting of this year’s crop. In the UK, Prince Charles was at the forefront of trying to get the English to go out into the fields.

Both attempts were unsuccessful.

Jobs Norwegians don’t want

“The challenge is that migrant workers do the jobs that a country’s own population no longer wants to do. These are jobs that are often poorly paid, poorly regulated, monotonous, dirty and sometimes dangerous,” says Rye.

Norway has become more dependent on labour migration than most people realize. Professor Johan Fredrik Rye studies labour migration. Photo: NTNU

When migrant workers take over manual jobs, the status of those jobs drops further and makes them even less attractive to local people. The emphasis is more on the employer’s needs than on the employee’s right to a decent job, according to the migrant researcher.

New book on labour migration

Karen O’Reilly and Rye teamed up to edit the recently published book entitled International Labour Migration to Europe’s Rural Regions.

“Migrant workers and seasonal workers are marginalized, invisible and exploited.”

The book includes contributions from a number of research groups that have studied different aspects of the diverse labour migration patterns in Europe.

Migrant workers range from Russians and Poles in the Norwegian fishing industry, Polish seasonal workers in container barracks on German farms and Thai berry pickers in Swedish forests, to Ukrainian farm workers in Poland, Eastern European strawberry pickers in Norway and England, Albanians in Greek agriculture and shepherds in the Mediterranean countries.

Two chapters compare American and European agriculture.

Difficult to change

Rye and O’Reilly are clear on what the research shows: migrant workers and seasonal workers are marginalized, invisible and exploited.

“Poor working conditions and low status characterize Norwegian rural communities more than before and will continue to do so. Migrant workers often find themselves in the marginal zone of the regulated labour market, both in Norway and elsewhere in Europe,” says the sociologist.

“A lot of people are trying to change these conditions, but it’s tough, even when you try to pass laws to regulate working life. The problems lie more with how global food production is organized than in the unwillingness of individual employers,” he said.

The researchers believe Europe is on the same course as the United States in terms of the industrialization of agriculture.Photo: Johan Fredrik Rye

Change is difficult because farming needs to be profitable, so the wage level has to be kept low.

Consumers are happy to say yes when asked if they would be willing to pay a little more for their food if it were produced in a more responsible way, but when they’re actually shopping they opt for the cheapest choice. It’s not easy to do anything about that, Rye says.

Good labour force – poor treatment

According to Rye, migrant workers are expected to work hard – and settle for little.

Poles in Norway are said to be ideal workers despite the fact that their living conditions are poor and isolated. Similar situations are found all over the European continent. For example, Romanian strawberry pickers in Andalusia are housed in rooms with anywhere from two or six others. They’re far from home and are only minimally integrated into the host culture.

Common to the various host countries is that the authorities ignore the migrants’ poor working and living conditions. Recruitment companies minimize the possibility of employees participating in collective bargaining schemes.

“Working life in Norway is among the most regulated in Europe. It’s a good starting point. But at the same time, the state’s attention has been less focused on some parts of working life in the rural districts. The labour market in rural areas may seem more immune to attempts at state regulation, making migrant workers’ ability to organize that much harder,” says Rye.

“The system maintains an idyllic image of a triple-win from labour migration.”

“Triple-win”

More than almost any other industry, food production depends on migrant workers. Employers defend low wages by saying that migrants earn much more than they would in their home country.

Karen O’Reilly has published a book on European labour migration with Johan Fredrik Rye. Photo: NTNU

“The system maintains an idyllic picture of a triple-win in labour migration: the employer gets good, cheap labour, the employee earns more than at home, and the family and home country benefit from it,” says Rye.

Many reasons

Rye points out that major geopolitical changes have influenced labour migration in Europe.

The fall of communism, EU expansion, globalization and the dismantling of national borders have enabled extensive labour migration. Cheap flights have made it easy to get around. In theory, you could live in Gdansk and commute weekly to Norway. The book refers to the fact that there are 5.5 million migrant workers in Europe, and says that the actual number is probably even higher.

From farm to industry

Agriculture in the United States is highly industrialized. The country’s two million farmers produce as much as 10 million farmers do in the EU. American working life is also far less regulated, less unionized and the welfare schemes much worse than in Europe.

Rye says that large parts of the agricultural and food production sectors in Europe are heading into a similar kind of industrialization at full speed.

“This is most evident in labour-intensive fruit and vegetable production in the Mediterranean countries, such as in southern Spain, where a 450 square kilometre area is covered with plastic for growing vegetables,” he says.

“But agriculture is becoming much more centralized in Norway too. Small farms are dying out and being replaced by much larger enterprises. This development sets the stage for bringing in more farm workers from abroad,” Rye said.

- You might also like: Less sleep reduces positive feelings

Hope as driving force

Labour migration has a lot to do with emotions, Rye said. The driving force for migrant workers is most often the hope of a better life for themselves and their families. But for many of them, it’s a demanding life, even if they make more money than at home.

Jobseekers leave home and often have to live in a shared household. That might not pose a problem for a young Swede who’s spending a few months cleaning crabs on the Norwegian coast. It’s something else for a father with three children back home in Poland.

“Migrant workers live a kind of shadow life. They aren’t in their home country nor are they part of the community they’ve come to for work. Right-wing populism in Europe is strongest in rural areas, which probably affects migrant workers in some countries. The main impression in the Norwegian debate, however, is that people have a positive view of labour migration from Eastern Europe,” says Rye.

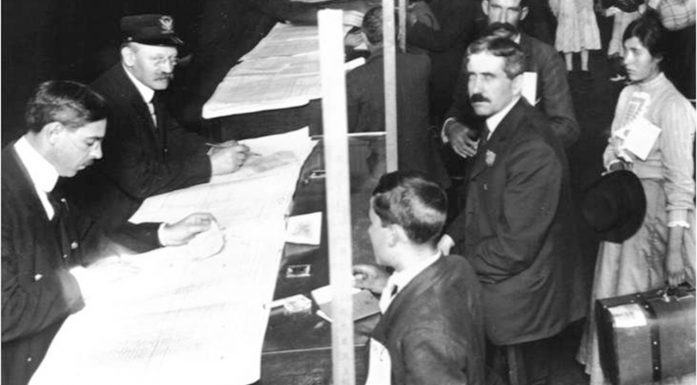

Major geopolitical changes have influenced labour migration in Europe. The fall of communism, EU expansion, globalization and the dismantling of national borders have enabled extensive labour migration, says Professor Rye. Photo: Johan Fredrik Rye

Broad spectrum

The researchers’ use a broad definition of “migrant worker.” It includes Poles who have worked in fish processing on Frøya island for ten years and Thai berry pickers who comb Scandinavia’s forests for a few weeks.

A high percentage of those who come to Norway as refugees also end up in low-paying agricultural jobs or in the food industry in rural areas. Getting a job without a Norwegian education and with poor language skills is difficult.

Reference: International Labour Migration to Europe’s Rural Regions, edited by Johan Fredrik Rye and Karen O. Reilly, Routledge.